I guess you could say the low point arrived on March 27, 2022, with the broadcast of the 94th Academy Awards. No, the “slap heard ’round the world” wasn’t it—though that cast a pall over the proceedings, didn’t it?—but the constant, almost jubilant, belittlement cinema received by the very ceremony created to champion it.

“Here at the Oscars, where movie lovers unite and watch TV,” host Wanda Sykes said in a scripted intro. “They weren’t all great,” host Amy Schumer said of the nominated movies. “I didn’t see many—any of them. I didn’t see them.”

Animation was maligned as mere kiddie fair, a handful of production awards were handed out while the stars were still walking the red carpet, and there was that whole #OscarsFanFavorite thing. All this after two years of a pandemic that disrupted productions, neutered releases and shuttered the very spaces moviegoers called home for over a century.

Not that things were that rosy in the first place. A rise in fanboy culture poisoned the well, turning casual discourse into coordinated toxic affairs, while the streaming wars eroded the viability of communal conversation.

Back before the launch of Netflix Instant in 2007, the DVD mailing service offered a massive catalog of films from far and wide, old and new, for a relatively low price and the convenience of having the movies come to you. Before that was Blockbuster, Hollywood Video and a battery of mom-and-pop rental shops across the U.S. Before them were film societies, second-run theaters and art house cinemas connected to museums and universities. It might take some doing, but the best movies—new and old, mainstream and underground, domestic and foreign—were never out of reach.

That was then. These days, streamers’ catalogs are so limited that the typical viewer subscribes to multiple services to keep pace. Once were the days when even the most casual moviegoer could watch the best picture nominees. Now you’re SOL if you have a Hulu account but not Apple TV+.

Has cinephilia ever felt this fractured?

Darkest before the dawn

Yet there is hope, and it comes in the shape of a British film magazine.

This November, Sight & Sound will announce its once-a-decade poll of the greatest films of all time. Invited critics, programmers, academics, distributors and writers from around the globe submit ballots of what they consider to be the 10 greatest movies—with the definition of the word “greatest” left up to each individual. From these ballots, Sight & Sound tabulate the frequency of each title to determine a list approaching definitive.

Officially, the tradition dates back to 1952 when 63 critics dubbed Vittorio De Sica’s neo-realist masterpiece, Bicycles Thieves, the best. Ten years later, 70 respondents to Sight & Sound’s call placed Citizen Kane on the pedestal, a spot it would occupy until 2012, when 846 respondents from 73 countries knocked Kane out in favor of Vertigo.

Interestingly, the roots of the poll can be found in a 1941 Sight & Sound column, “Quiz on Film Classics.” There, writer Charles Oakley opined that the larger moviegoing audience lacked critical appreciation. “They have little understanding of why they liked or did not like the film—partly, no doubt, because their reactions to it were mainly emotional; but partly also because they have never been given any guidance on how to like films,” Oakley wrote.

His solution: Teach film appreciation. “This can be done by selecting, say, 10 outstanding fiction films for screening as ‘classics’ in schools, and by preparing a textbook for teachers.”

Oakley was on to something; his suggestion of a top 10 is part of a long lineage of list-making and discussion. The titles Oakley chose elicited passionate letters from readers, enough that Sight & Sound decided to make more of it. Eight decades later, here we are.

Turning content into conversation

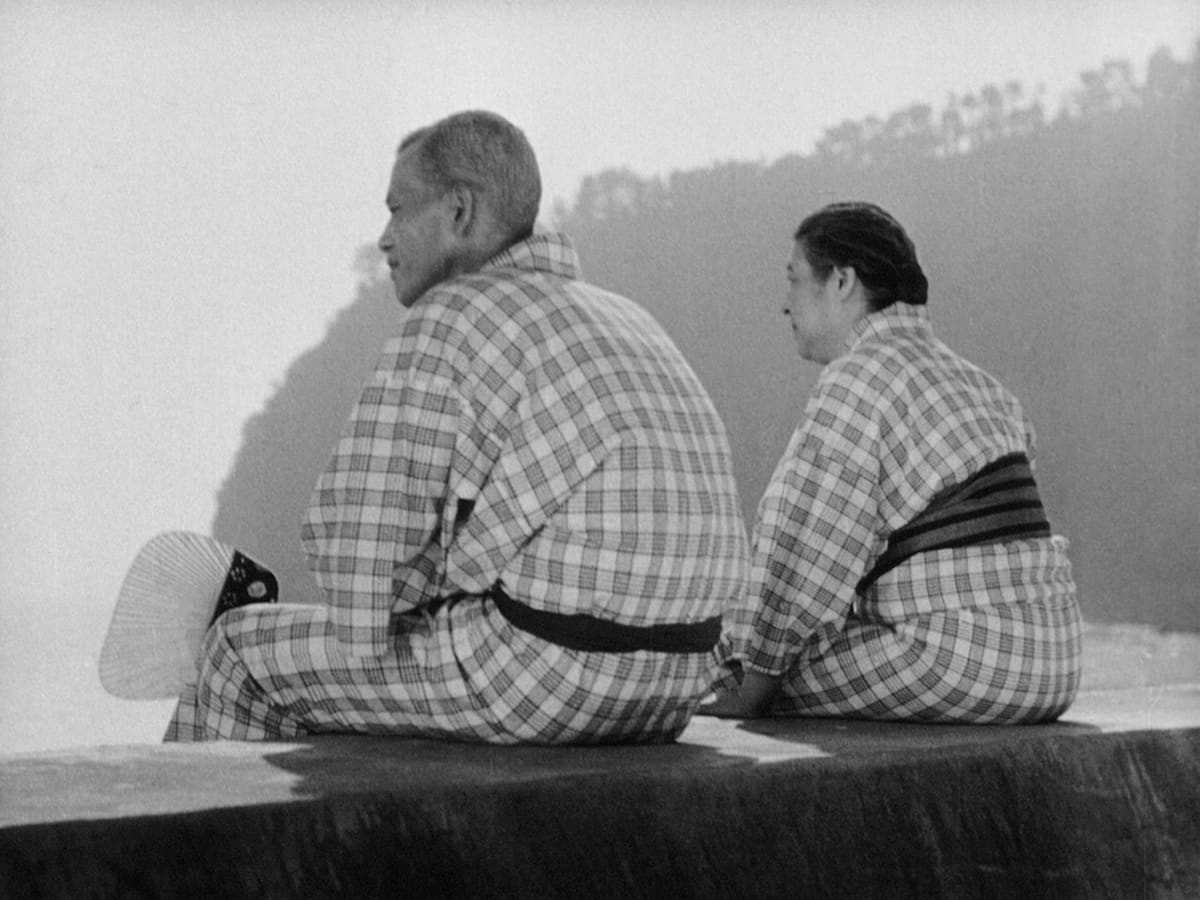

One of the upsides of Sight & Sound’s poll is that the results are a starting point. I became aware of Sight & Sound’s top 10 after the 2002 results were published. Nine I’d seen, so I sought out the blind spot: Yasujirô Ozu’s remarkable Tokyo Story. It opened a door in my soul. When the 2012 results were published, Sight & Sound ran the top 10 alongside the top 100 vote-getters. A few weeks later, Sight & Sound posted all 2,045 nominees. Titles leaped off the page and into my queue: The Mirror, Shoah, Touki Bouki, The Color of Pomegranates, Barry Lyndon—the list went on.

One of the thrills in anticipating Sight & Sound’s 2022 poll is the thought of how many movies I will encounter because of their inclusion. There’s a chance that this year’s poll will further codify the cinematic canon by retaining the same titles and filmmakers it always has. There’s also a chance that this year’s poll will tear all that down in favor of a new list that moves cinematic appreciation out of the 20th century. Either way, the poll—in its traditional 10 titles and expanded version, whatever count that may be—is destined to launch a thousand reactions, corrections and appreciations.

Whether it was Oakley’s aim to encapsulate the history of the seventh art or to entice viewers into cinematic exploration with his “Quiz on Film Classics,” it appears he accomplished both.

Cinema 101

I’ve been writing about movies for over a decade now. Along the way, I’ve been asked countless times what the best movie is (Citizen Kane is the easy answer, and maybe the correct one) and what my favorite movie is (changes frequently, it might be Kane these days).

Then there are the questions of what to watch, be it what’s in theaters now or where to start with a particular filmmaker, genre or industry. I adore these questions because the options are so varied. Sure, I want you to watch the best movies, but I’d rather you watch the movies that make you excited to watch more movies.

So, in anticipation of Sight & Sound’s poll and the spirit of students returning to school, I give you my list, Cinema 101: A trip through 141 years of movies. Some of the titles are familiar. Some you might find peculiar. All, I think, are worth your time. But I suppose that’s up for you to decide.

A few notes

Defining what is and is not a movie in 2022 can be tricky. Is it exhibition? Duration? Style? Some serialized shows (Twin Peaks: The Return, True Detective, etc.) look and behave like long movies. Read reviews, and you’ll see the word “cinematic” tossed around like it means something. Then there are those works that debut at film festivals, move to streaming and win Emmys. More still are produced by streaming services, play a theater for one week in New York or LA and get nominated for 11 Oscars. The definitions are bleaching.

To streamline matters, I’ve chosen movies that most will recognize as moviegoing experiences. Krzysztof Kieślowski’s incomparable Dekalog may have played theaters here and there, but it was made for Polish television and is most likely to be experienced by anyone discovering it today as 10 separate episodes. It’s incredible, but you won’t find it listed here. You will, however, find Kieślowki’s magnificent Three Colors trilogy (Blue, White and Red) listed as one. Yes, they are three separate movies, and you may watch them as such, but I find it impossible to think of one without the others. Not so with Star Wars and The Godfather—one title for each franchise. My rules, you see, are arbitrary.

I’ve also grouped a handful of early shorts as the 101st entry. A couple of them can stand as individual works shoulder-to-shoulder with the rest of the list, but I find that watching them together provides a much deeper understanding of cinema’s early days. You will see a visual language form before your very eyes.

What’s missing? Plenty. I started this list with about 3,000 titles, so you can imagine the sheer depth of what was left off. As I culled, I wondered if a second list—perhaps called “So Dear to My Heart”—might be necessary. But a second would lead to a third, a fourth and so on. Like the universe, cinema is expanding.

The beauty is in the sharing. Cinema is never dead, but love for the form and interest in its ability to communicate waxes and wanes in cycles. Today feels low, but I think tomorrow holds promise. As long as we keep watching and talking, things are bound to get better.

Email: [email protected]

Cinema 101: The movies

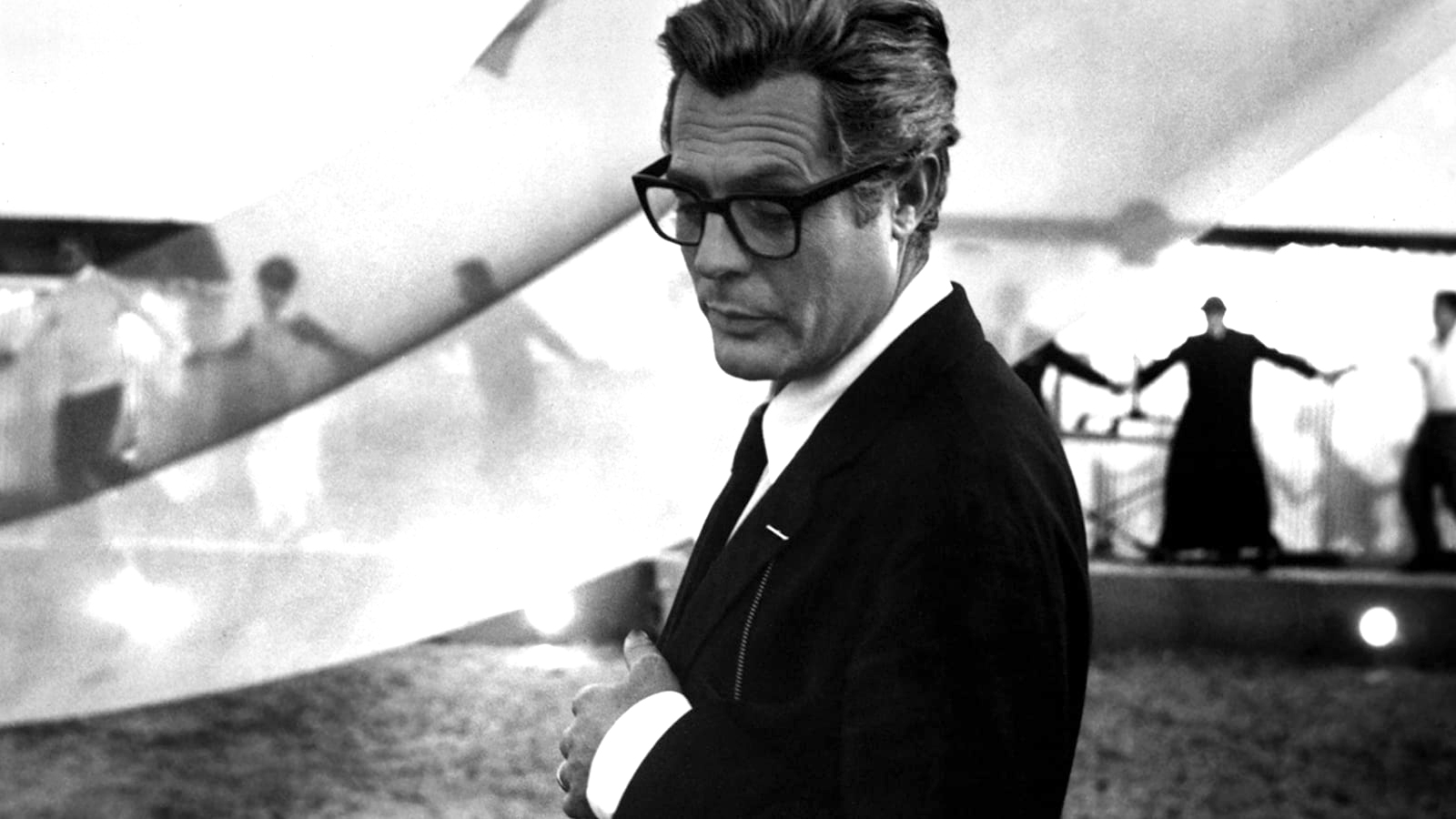

1. 8 1/2 (Fellini, 1963)

2. After Life (Kore-eda, 1998)

3. Apocalypse Now (Coppola, 1979)

4. An Autumn Afternoon (Ozu, 1962)

5. Babette’s Feast (Axel, 1987)

6. The Battle of the Century (Bruckman, 1927)

7. Beau Travail (Denis, 1999)

8. Bicycle Thieves (De Sica, 1948)

9. Bonnie and Clyde (Penn, 1967)

10. Born in Flames (Borden, 1983)

11. Bowling for Columbine (Moore, 2002)

12. Breathless (Godard, 1960)

13. Cameraperson (Johnson, 2016)

14. Casablanca (Curtiz, 1942)

15.Charade (Donen, 1963)

16. Chimes at Midnight (Welles, 1965)

17. Chinatown (Polanski, 1974)

18. Citizen Kane (Welles, 1941)

19. Come and See (Klimov, 1985)

20. Cries and Whispers (Bergman, 1972)

21. Day for Night (Truffaut, 1973)

22. Do the Right Thing (Lee, 1989)

23. Dont Look Back (Pennebaker, 1967)

24. Double Indemnity (Wilder, 1944)

25. Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind (Gondry, 2004)

26. The Five Obstructions (von Trier/Leth, 2003)

27. The General (Keaton/Bruckman, 1926)

28. Girlfriends (Weill, 1978)

29. The Gleaners and I (Varda, 2000)

30. The Godfather (Coppola, 1972)

31. Gone With the Wind (Fleming, 1939)

32. GoodFellas (Scorsese, 1990)

33. Grand Illusion (Renoir, 1937)

34. Grave of the Fireflies (Takahata, 1988)

35. The Great Dictator (Chaplin, 1940)

36. A Hard Day’s Night (Lester, 1964)

37. Hiroshima Mon Amour (Renais, 1959)

38. The House is Black (Farrokhzad, 1963)

39. House of Flying Daggers (Yimou, 2004)

40. The Hustler (Rossen, 1961)

41. Inside Llewyn Davis (Coen/Coen, 2013)

42. Inside Out (Docter, 2015)

43. Jaws (Spielberg, 1975)

44. Jeanne Dielman, 23, Quai du Commerce 1080 Bruxelles (Akerman, 1975)

45. Kiss Me Deadly (Aldrich, 1955)

46. La Dolce Vita (Fellini, 1960)

47. The Lady Eve (Sturges, 1941)

48. The Last Waltz (Scorsese, 1978)

49. The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp (Powell/Pressburger, 1943)

50. The Long Goodbye (Altman, 1973)

51. Los Angeles Plays Itself (Andersen, 2003)

52. Léon Morin, Priest (Melville, 1961)

53. Mad Max: Fury Road (Miller, 2015)

54. A Man Escaped (Bresson, 1956)

55. The Many Adventures of Winnie the Pooh (Reitherman/Lounsbery, 1977)

56. A Matter of Life and Death (Powell/Pressburger, 1946)

57. Merrily We Go to Hell (Arzner, 1932)

58. A Moment of Innocence (Makhmalbaf, 1996)

59. Mulholland Drive (Lynch, 2001)

60. My Man Godfrey (La Cava, 1936)

61. The Naked Kiss (Fuller, 1964)

62. Soleil Ô (Hondo, 1970)

63. On the Bowery (Rogosin, 1956)

64. On the Waterfront (Kazan, 1954)

65. Once Upon a Time in the West (Leone, 1968)

66. Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood (Tarantino, 2019)

67. The Ox-Bow Incident (Wellman, 1942)

68. The Passion of Joan of Arc (Dreyer, 1928)

69. Pat Garrett & Billy the Kid (Peckinpah, 1973)

70. Pharaoh (Kawalerowicz, 1966)

71. The Piano (Campion, 1993)

72. Pickpocket (Bresson, 1959)

73. Point Blank (Boorman, 1967)

74. Police Story (Chan, 1985)

75. Psycho (Hitchcock, 1960)

76. The Purple Rose of Cairo (Allen, 1985)

77. Rashomon (Kurosawa, 1950)

78. The Red Shoes (Powell/Pressburger, 1948)

79. The Searchers (Ford, 1956)

80. Shoah (Lanzmann, 1985)

81. Some Like it Hot (Wilder, 1959)

82. Spirited Away (Miyazaki, 2001)

83. Star Wars (Lucas, 1977)

84. Steamboat Willie (Iwerks, 1928)

85. Summer With Monika (Bergman, 1953)

86. Sunrise: A Song of Two Humans (Murnau, 1927)

87. Tangerine (Baker, 2015)

88. Taxi Driver (Scorsese, 1976)

89. The Three Colors Trilogy (Kieślowski, 1993-94)

90. Touki Bouki (Mambéty, 1973)

91. The Tree of Life (Malick, 2011)

92. Un Chien Andalou (Buñuel, 1929)

93. The Up Documentaries (Almond/Apted, 1964-2018)

94. Vagabond (Varda, 1985)

95. Vertigo (Hitchcock, 1958)

96. Vivre sa vie (Godard, 1962)

97. Wadjda (al-Mansour, 2012)

98. Wall-E (Stanton, 2008)

99. The Watermelon Woman (Dunye, 1996)

100. The Wizard of Oz (Fleming, 1939)

101.Early shorts: Sallie Gardner at a Gallop (Muybridge, 1878); Traffic Crossing Leeds Bridge (Le Prince, 1888); The Arrival of a Train at La Ciotat (Lumière, 1897); A Trip to the Moon (Méliès, 1902); The Great Train Robbery (Porter, 1903); The Dancing Pig (1907); Falling Leaves (Guy-Blaché, 1912); Suspense (Weber/Smalley, 1913); Gertie the Dinosaur (McCay, 1914)

For more, tune into After Image Fridays at 3 p.m., on KGNU: 88.5 FM and online at kgnu.org. Email questions or comments to [email protected].