It’s Monday around noon, and from space Boulder appears eerily quiet. The red brick of Pearl Street Mall is clearly visible, void of its usual lunch crowd. Broadway and 28th Street are clear of traffic. Cars are difficult to spot, save for a few scattered in mostly empty parking lots. The sports fields around the University of Colorado stand out, vast empty patches of green, despite the warm weather and spring air.

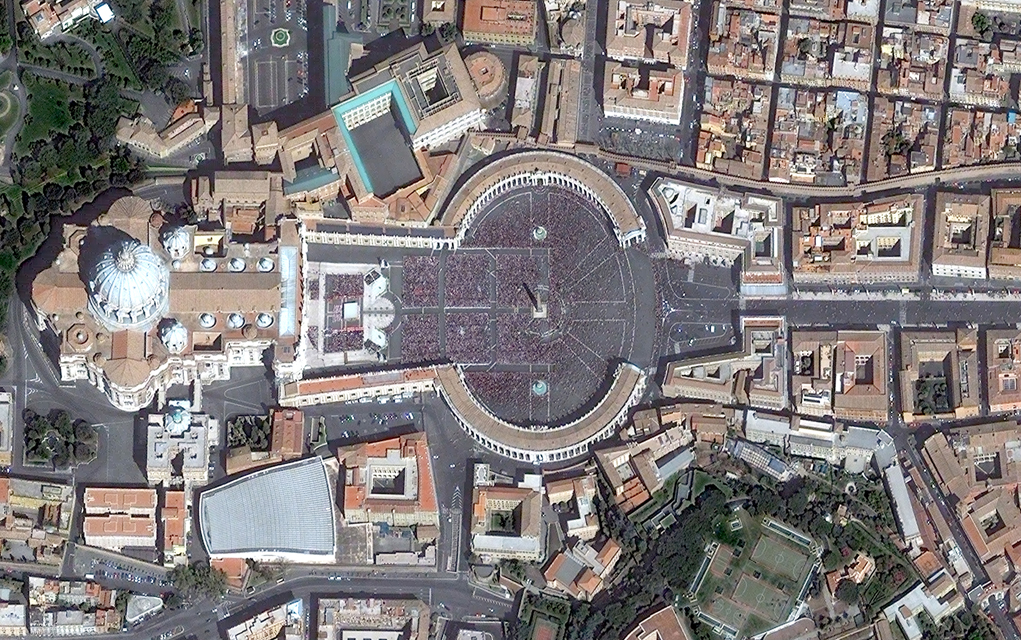

It’s April 6 and Boulder is a few weeks into its battle with COVID-19 — most businesses are closed; people ordered to stay home. All over the world, social distancing and quarantine policies seeking to slow the spread of the virus are visible from space. Places usually crowded with people are empty: St. Peter’s Square in Rome was bare on Palm Sunday. Mecca in Saudi Arabia, Tiananmen Square in China and the Piazza del Duomo in Milan appear the same. Airport parking lots are empty, but rental car lots full. Grocery stores are still rather busy. Side streets and city parking lots in Los Angeles are full of cars, but the notoriously busy freeways are clear, signs of commuters staying home.

“We’re trying to find what places has life been unchanged. And that’s a tough one,” says Stephen Wood, senior director of the Maxar News Bureau. “I haven’t really found a whole lot of places like that.”

For the last 20 years, Maxar, based in Westminster, has been sending its low Earth orbit imaging satellites into space and taking pictures all around the world, every single day. There are currently four working satellites covering 3 million square kilometers a day from 400 miles up in space. Every 90 minutes, each satellite makes a full orbit from the north to south, snapping photos as the Earth spins beneath it. Most Maxar images are captured between 10:30 a.m. and noon local time, hoping to take advantage of good lighting and minimal clouds that time of day.

“On every orbit we have a plan of what images we want to collect. We are constantly adjusting it,” Wood says. “It’s automated to an extent but there’s also manual intervention that will happen when there’s a breaking event or crisis, and obviously we’re dealing with plenty of that right now.”

Wood and his team first started tracking the impact of the coronavirus in January in Wuhan, China, although it was a bit tricky, he says, as it’s often cloudy in that part of the world. The city quickly began visibly shutting down, and a strict quarantine was put in place. As the streets emptied, hospitals in previously vacant lots began rapidly appearing to treat the onslaught of sick people, giving the outside world a clear picture of how quickly the disease spread.

“The imagery is extremely well suited for monitoring and measuring changes that are happening on the Earth,” Wood says. “Part of our whole premise is to have this imagery available and on the shelf before anybody even asks us to take a picture.”

Maxar has myriad projects it’s regularly working on: tracking geopolitical crises for defense and intelligence partners, base-mapping for autonomous driving vehicles, supporting NASA’s climate change program, and surveying the aftermath of natural disasters to help local and federal officials respond, for example.

“We operate on a push-pull system,” Wood says. “Sometimes, it’s something that nobody’s asked us for, but we catch it. It could be something dramatic like crowds or demonstrations or military activity or natural disasters that we happen to catch. … The other flip side is that we receive requests all the time and so we were constantly juggling those things that we’re pushing out as well as the way that we need to respond to the inbound requests.”

Right now, he says, both his team and customers alike are concerned with tracking the economic, social and medical impacts of the pandemic.

It seems like the whole world is shutting down for the most part, Wood says. Busy marketplaces in Africa have slowed, large populated metropolises in India like New Delhi, Calcutta and Mumbai are showing signs of national lockdown. Miami beaches were empty late last month despite concern that spring breakers were going to flock the area in defiance of national guidelines. Even North Korea has all but stopped its trading of coal and other resources with China, something international sanctions have failed to do.

But it’s not just the absence of activity that’s catching Wood’s eye. More testing sites and field hospitals are popping up around the world. Large tents are filling stadiums in Sao Paulo, Brazil, and Lagos, Nigeria. Cars are lining up at testing sites outside stadiums in Florida, Maryland and New Orleans. A field hospital recently popped up on the edge of New York’s Central Park, the white geometric shapes appearing as a stark contrast to the green fields on one side and skyscrapers on the other.

“To me some of the more striking ones have been places that I’m super familiar with, like Denver International Airport,” Wood says. “There’s a difference when you’re seeing something from an overhead perspective and then when you’re able to actually walk around on the ground and see that right up close.”

During the 2013 Boulder County flood, for example, Wood, who lives in Niwot, would scan the satellite imagery of the floodplain, brown waters swirling through Boulder, Longmont and Lyons. Then he’d go out to help clean up neighbors’ homes, his feet walking around the area he had just been observing from hundreds of miles above Earth.

But even the flood doesn’t quite compare to our current moment and the visible changes that can be seen from space.

“This is global, there’s no place that I don’t think this hasn’t touched at this point,” he says. “And that makes it by itself more complicated and more expansive than any crisis I’ve ever dealt with before.”

Keep scrolling for an image gallery of Maxar’s images.