“I know it’s hard to believe, but these days I feel upset a lot of the time,” says artist Kathryn Jill Johnson with a laugh.

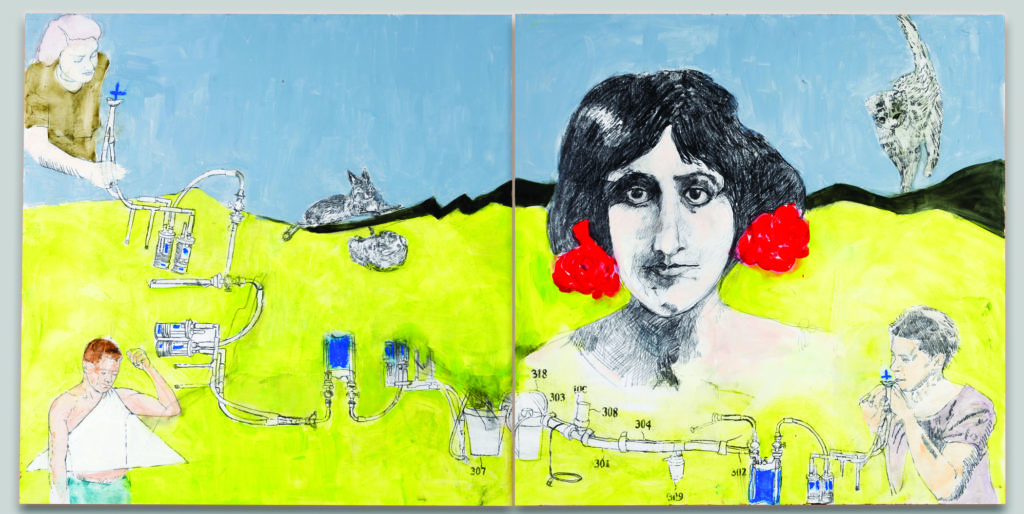

With the never-ending barrage of crises in our country, we are all tasked with navigating the turbulent waters of everyday life. Like many artists, Johnson pours her frustration into her work. In her piece “Speaking Cycle,” multiple figures are seemingly connected by a series of tubing. While there’s a notable line of communication, the relationship between figures is unclear and it leaves the viewer questioning the validity and substance of the information being presented.

“[I wasn’t] really thinking, ‘Oh I’m putting this in the work,’” she says. “But then when I started looking at the whole body of work I [noticed] it’s all about people who aren’t being heard, and people not saying what they mean, and [asking] who deserves to be listened to. I didn’t realize I was doing work about that.”

Johnson is one of three artists featured in the Firehouse Art Center’s latest exhibit Interesting Times, now showing through Sept. 1. She is joined by Samantha Simpson and Robin Hextrum, who each digest the current political era to create art examining the palpable tension in the air.

Their work — opulent and fantastical in different ways, sometimes dark and sinister, sometimes bright and lively — gives viewers an anchor of sorts to drop, a place to stop and refocus. Curator Brandy Coons points to political unrest as the glue between the artists and their work.

“People [in the art world] say, ‘Oh we’re in troubling times,’ but the plus side of that is good art might come of it,” Coons says.

Each artist uses a different approach. Johnson’s work features various elements — people and contraptions — that are realistic, yet they’re stitched together in a way that isn’t obvious. Johnson uses her intuition to create the pieces, and she frequently draws inspiration from the likes of old portraiture and medical textbooks from the 1950s.

The pieces give off a sinister quality as the viewer tries to manufacture a storyline. There are themes of disruption and miscommunication, creating a broken narrative.

“It’s a leap to create [a] story out of the information she provides, and so there’s a sense of uncertainty,” Coons says. “There’s a tension there between what is solid and what is unreliable.”

Indirectly, Johnson’s work captures the eerie, confusing feeling that is so prominent when trying to make sense of what’s happening in the world.

It’s a common thread in the show, continuing with the work of Robin Hextrum. Her series currently on display at the Firehouse started in the summer of 2016 before the presidential election. Hextrum set out to make a body of work that would respond to the chaos and intensity she was perceiving.

Different from Johnson’s dark and dubious tone, Hextrum’s work is colorful and bright. Hextrum also uses formal elements to achieve a sense of unease. She notes the long-time debate between art schools of abstraction and realism, but instead of committing to one, she blends the two. In “Final Days,” a painting Hextrum made the day after Trump was elected, a realistic Rottweiler bares its teeth and leaps in the midst of heavy brush strokes in a variety of colors. The juxtaposition between styles in her paintings unsettles and disorients the viewer.

“There’s this sense of instability that they’re capturing, this sense of urgency,” Hextrum says.

Also featured in the exhibit is the work of Samantha Simpson. Inspired by epic storytelling, Simpson created her series Saga, which she started making in 2017. And while Johnson and Hextrum imply their political motivations, Simpson uses some concrete examples from the White House. Her large-scale paintings feature a multitude of animal characters interacting with each other — the frogs in her paintings flee to safety while under attack by a giant snake or a flying insect with the head of Paul Ryan, or a bat that looks like Steve Bannon.

Simpson uses animal imagery as a way for the viewer to identify with her characters. The frogs in her paintings aren’t Democrats or Republicans, but animals helping Simpson to bring her point home: When a frog is next to a snake, it can quickly become prey.

“I’ve been feeling very helpless as one little person in this country,” Simpson says. “I feel like these paintings were a way to talk about negotiating threats and trying to negotiate politics as someone who’s small. There are these little frogs, and they’re under threat from [predators] in each painting, but they’re also responding in different ways.”

The idea of agency was an important aspect to Coons when curating the exhibit. She saw all three artists using their skills as a way to respond to situations out of their control. Instead of doing nothing, they exercised their own power to create art.

Each artist questioned their role in society — just as anyone concerned with the state of affairs feels called to do more. Hextrum asked herself if it even made sense to make art anymore, or if she should be protesting in the street every day instead. It caused her to pause and reflect, and she eventually made a shift to be more thoughtful in her creations. She sees expression and connection as vital for the survival of the community.

“I think now more than ever it’s important to pause and be with art objects that have some sort of grain of vulnerability and sincerity in their execution and that allow us to reclaim that sense of humanity and human experience,” Hextrum says.

Art serves as a place to land that allows for contemplation and absorption, and that’s what Interesting Times invites the audience to do. But instead of participating in a heated political debate or watching talking heads spin a situation on Fox News, the exhibit presents another quality with which to engage: beauty. There is an aesthetic allure in all the works presented in Interesting Times. “Each [artist] succeeds in creating beauty within the chaos: inviting us in to a resting place for worried minds,” Coons writes in a statement for the exhibit.

Simpson sees beauty as a tool used to seduce the viewer and to make the art more accessible. Hextrum and Johnson also see the value in making attractive work as a gateway to invite the viewer to start processing these dense topics.

“The sense I get from all the paintings is being able to hold on to something beautiful even if you’re touching on something that’s painful or ugly or difficult, but still being able to explore that in a beautiful visual way,” Johnson says.

And as one of art’s inherent purposes, the pieces in the exhibit create light from darkness. Beauty itself can be conflicting, Coons says, because people associate it with peaceful feelings or positivity, but she points to the artists in the show who have used it to conceptualize conflict and tension.

Tension is a clear center point in Interesting Times — between present and future, known and unknown, peace and disturbance. Even the formal elements of the paintings further the conversation, like Hextrum’s blending of abstract and realism or the disjointed pairings in Johnson’s work. While two seemingly opposite factors are pushed together, there is no clear end game that emerges.

“I think the point of them is that the outcome is uncertain,” Coons says. “When we talk about what good art does, it’s that it doesn’t answer any questions for us, but it helps us identify the questions that are most important. It makes us think. What all three of these artists are doing really well is presenting the question in various contexts.”

The takeaways vary for each artist, but Hextrum sees her work as a “tragic mirror” into which society can peer. In “Fallen Swan,” a dead swan lies among an explosion of flowers and plants. It can serve as a cautionary tale, Hextrum says, or a tragic altar for the perilous environment we’re living in. Yet Hextrum also sees optimism in her color palette and lush scenes. There’s a small glimmer of hope and triumph.

“You get this sense of renewal or of nature always being able to somehow outmaneuver the trials that are thrown at it,” she says. “It’s a little bit of the same feeling you’d have seeing grass through cracks in the concrete. It’s going to somehow evolve or somehow work its way through regardless of the insane things we’re throwing at it.”

As Coons suggests, Interesting Times provides no concrete political agenda or solutions. But Johnson sees the potential of art itself as a solution.

“With art you can really get at things in a way that you can’t get at by rationality or even with just flat out anger and fury. Art is an important part of being a person,” she says. “I wish everyone would just make some stuff. Then I think everyone would feel better.”

ON THE BILL: ‘Interesting Times.’ Firehouse Art Center, 667 Fourth Ave., Longmont. Through Sept. 1.