Strikes have been breaking out all over the country. According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, some 485,000 workers were involved in strikes in 2018. This was the largest number since 1986.

Tens of thousands of K-12 teachers have gone on strike in Republican-dominated states such as West Virginia, Oklahoma, Kentucky, North Carolina and Arizona, but also in California, Colorado and Pennsylvania. The fever spread to hotel workers in several cities, university employees (grad students, regular staff and faculty), Lyft and Uber drivers and tech employees at Google and Amazon.

Why is this happening? We may have an economic “recovery” but many ordinary people don’t feel like celebrating. Profits are definitely up, and the unemployment rate is low. But wages are stagnant and income inequality is grotesquely high. Historian Colin Gordon notes in Dissent:

“One in four U.S. workers labor in low-wage jobs (those paying less than two-thirds of the median wage) — easily the highest rate among our democratic and economically developed peers, and a rate that is growing. Since 2007, the lion’s share of new jobs has been in lower-wage occupations than those lost during the preceding recession. And projections of future job growth are heavily skewed toward low-wage service occupations.”

The labor movement’s invigorated militancy reflects the spirit of the times, according to Sharon Block, executive director of the Labor and Worklife Program at Harvard Law School. She told veteran labor reporter Steven Greenhouse, “When there’s a lot of collective action happening more generally — the Women’s March, immigration advocates, gun rights — people are thinking more about acting collectively, which is something that people hadn’t been thinking about for a long time in a significant way.”

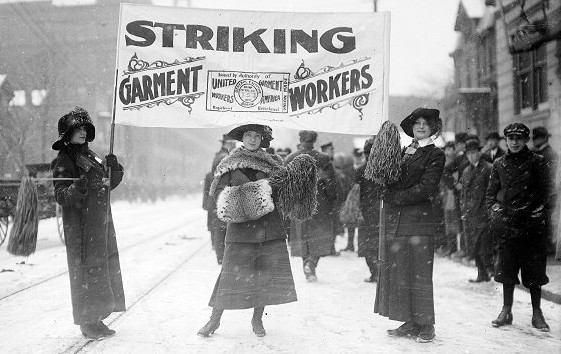

Women are frequently playing a dominant role. In his piece in The American Prospect, Greenhouse quoted Rebecca Garelli, a seventh grade math and science teacher in Phoenix who was one of the leaders of the Arizona strike. She said Donald Trump and Education Secretary Betsy DeVos “fired up a lot of people. Then you have Black Lives Matter, #MeToo, and the women’s movement, and the growing resistance, especially among women — remember teaching is over 70 percent women — and all the talk about arming teachers, and a lot of teachers just got fed up and angry.”

Will this wave of strikes lead to a sustained resurgence of the movement? Unions have been severely weakened and have been on the defensive for decades. They have suffered from offshoring of jobs and weakened labor laws. They have been battered and bruised by aggressive attacks by corporations, the courts, right-wing billionaires and GOP politicians. The share of workers who belong to a union is now 10.5 percent. For private sector workers, it is 6.4 percent. Public sector unions are stronger but their power is unevenly distributed. In the last several years, the right-wing has relentlessly attacked their bargaining rights, particularly in Republican-controlled states.

Back in the 1950s, unions were a much stronger political and social force. Almost one-third of all workers were unionized. For decades, unions boosted wages for all working people. When the percentage of workers who are union members is relatively high, wages of non-union workers also benefit. Non-union employers increase pay and benefits in order to prevent their workers from unionizing.

Unfortunately, the opposite is true. Numerous studies have shown that declining unionization is a crucial reason for the precipitous deterioration of American living standards. From one-third to one-fifth of the growth in inequality is due to the decline of unions, according to a 2011 study in the American Sociological Review by Bruce Western of Harvard University and Jake Rosenfeld of the University of Washington. They conclude:

“In the early 1970s, unions were important for delivering middle-class incomes to working-class families, and they enlivened politics by speaking out against inequality… These days, there aren’t big institutional actors who are making the case for greater economic inequality in America.”

What can be done? In electoral politics, unions obviously support candidates who are the most pro-labor, pressure the wishy-washy ones and try to defeat their enemies. But they also play a significant role in pushing for legislation that benefits all working people, such as progressive taxation, expanded Social Security, affordable health care, and extended sick time and family leave.

In organizing, unions sometimes reach out to the public and attempt to pressure companies with corporate campaigns (using investor pressure and media shame tactics), engage in one-day publicity strikes and join in social justice coalitions with community and faith groups.

It is a tough fight. The power of big business and their buddies in government seems overwhelming. As an individual, you can feel helpless. But we are powerful when we unite. That is what unions are all about.

this opinion column does not necessarily reflect the views of Boulder Weekly.