Last year was the fourth hottest year on record, topped only by 2016, 2015 and 2017 in that order, NOAA announced on Feb. 6. The same day, scientists and lawmakers alike took to Capitol Hill in the first hearings about our warming climate in the federal legislature since 2010. Less than 24 hours later, Democratic lawmakers revealed their Green New Deal, a sweeping proposal to forsake fossil fuels for renewable energy in an effort to curb global warming while reinvigorating the economy in the process.

Hardly a day goes by when climate change doesn’t make headlines. And rightfully so, given how greenhouse gas emissions, fueled by the extensive use of fossil fuels, are drastically warming the atmosphere, melting sea ice and changing weather patterns around the world.

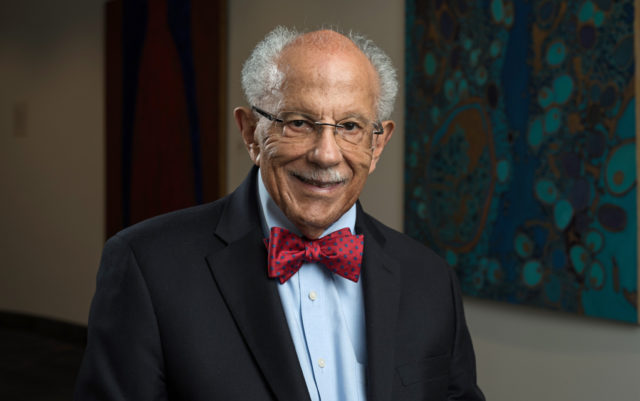

We know all of this, in large part, due to Dr. Warren M. Washington, a meteorologist and atmospheric scientist who pioneered computer global climate modeling in the 1960s as a research scientist at the National Center for Atmospheric Research (NCAR).

Washington was recognized on Feb. 12 with the prestigious Tyler Prize for Environmental Achievement for his “courage and commitment to inform and advance public discourse and policy on climate change, as well as inspire civic engagement to take action to protect the planet and people,” according to the prize committee. He shares the honor with fellow climate scientist Michael E. Mann and is the first African-American to receive the award.

Washington has worked at the intersection of climate science, diversity and politics for decades, advising six presidents from Carter to Obama on climate change, mentoring countless students in the atmospheric sciences, and continuing to inform our understanding of climate change every step of the way.

Despite advice early in his academic career to give up his pursuit of physics for an “easier” field like business, Washington says he’s naturally stubborn. When it came time to get his doctorate, he was a bit taken aback when Florida State asked him to send in a photograph of himself before they would consider his application. It was 1959, and Washington hadn’t realized the school was still segregated (it didn’t admit its first African-American student until 1961.) Washington eventually attended Pennsylvania State University and became the second African-American to ever receive a Ph.D. in meteorology.

He came to NCAR in Boulder in 1963, and through collaborative work with other NCAR scientists, including Akira Kasahara, took the basic principles of math and physics, along with emerging computer technology, to create climate models of the atmosphere. Later he incorporated oceans and sea ice into his work, and his modeling became the basis for what scientists around the world use today to project both past and future global climate change. Throughout his career, Washington has worked tirelessly to communicate his research to lawmakers and the public, helping to inform major climate policies both nationally and internationally.

“I’ve tried to do my part,” Washington says. “I just always felt like I had to spend some of my time doing these sort of things.”

He became the first African-American to be president of the American Meteorological Society (AMS) in 1994 and he served on the National Science Board for decades, culminating in his chairmanship from 2002-2006, a distinction that makes Washington particularly proud.

The Tyler Prize is only the latest recognition of Washington’s contribution to climate science. He was among the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) scientists who won the Nobel Peace Prize in 2007. And in 2010, President Obama awarded him the National Medal of Science. The Tyler Prize, however, comes with a cash prize of $200,000, which Washington plans to use to set up scholarships for minority students in science at his almae matres of Oregon State and Penn State.

Starting in the 1970s, he’s traveled the country encouraging black, Hispanic and Native American students to pursue the sciences, atmospheric sciences in particular. Now, he says, AMS has more than 100 minority scientists among its ranks, a sign of how far we’ve come, how much progress is being made.

“I think that science has always benefited from having people from different backgrounds and experiences contributing to the overall knowledge that comes out of climate change or science in general,” he says.

Washington has remained unphased by the skepticism he’s faced over the last 50 years, not least of which includes a handful of death threats, some as recent as three or four years ago.

“In science, we always have skeptics and they keep us on our toes,” he says. “There are essentially two types of skeptics: ones that are generally bringing up issues that need to be looked into. But then there are the skeptics who just say anything to support their position.”

Throughout his career, he’s welcomed the first type, and largely ignored the second, relying on the scientific process and not the court of public opinion to confirm his work.

“Additional research usually tries to answer the question of whether the skeptics are right or if the scientific community is,” he says. “That’s the way things ought to be settled.”

And at this point, climate change is more or less settled. Today, he says, citing a recent Yale study, 70 percent of Americans acknowledge climate change, and almost as many understand it’s caused by human activity.

But Washington isn’t one to preach doom and gloom. He’s optimistic, not only about our ability to make drastic societal changes, like the ones proposed in the Green New Deal, but also humanity’s ability to innovate. He looks at the wide range of growing technological advancements seeking to combat climate change — everything from wind and solar technology, to carbon capturing and drones planting trees in record numbers — and sees the potential to reverse course, a reason to hope.

Although Washington, now 82, formally retired from NCAR in July 2018, he recently bought a Tesla and still drives up from Denver several days a week.

“There’s no one thing that’s going to change things,” Washington says. “It’s the contributions of smaller things that grow over time.”

Ultimately, he says, “I’m hopeful for the future.”

And if Washington, a scientist whose life’s work has been to understand climate change, has not given up, perhaps we all have reason to be hopeful, too.