You’re at the theater, watching a lovely scene succumb to violence. You’ve just seen the marriage of a young couple but now, moments later, it’s just the bride and her mother-in-law on stage, alone together in a bedroom. The mother-in-law gets closer and closer to her new daughter, hurling accusations of infidelity until finally, she pushes her down onto the bed. You continue to watch as the young woman lies on her back, the elder holding her down so she can push her hand inside the young woman’s vagina to see if she is really the virgin she proclaims to be. The woman on the bed lunges back as the hand enters. Her hips shift, she leans her head back and gasps. Her eyes wince. She bites her bottom lip.

Just 20 feet from the action, the scene arouses sympathetic echoes in your own body and, as you recoil in your chair, a part of you wonders if you were supposed to see such intimate violence so closely. A part of you feels ashamed. A part of you experiences it as real.

No. You couldn’t see the hand enter the vagina and later, in hindsight, you can’t remember if the blood on the woman’s hand was real or imagined. Somehow the scene crossed the fine line between fact and fiction and you are left trying to understand it both ways, as experience and as art.

The scene has been designed to feel like it is real. All of the little details — the blocking, the acting, the lights, the sounds — tailored to trick your mind into forgetting the difference between realism and reality. This scene (from the play Wisdom From Everything, written by Mia McCullough and directed for Local Theater Company by Seema Sueko) owes its particular effectiveness to a woman behind the scenes, Jenn Zuko, who, if she’s done her job well, has afforded you the chance to experience something truly awful without ever knowing she had been there at all.

Up until this play, Zuko would have been classified solely as a “stage combat coordinator,” one of just a handful in Colorado. Academically trained and renaissance-faire verified, Zuko’s been working in stage since 1996, coordinating fight scenes for theater companies in Denver, Boulder and beyond. In the process she’s become one of Colorado’s authorities on the subject, a reputation in part earned by her book, Stage Combat: Fisticuffs, Stunts, and Swordplay for Theater and Film, which is pretty much required reading in theater classrooms across the state (in most of which she’s also taught or lectured).

Although unseen and often underappreciated, her job comes with a rich history in theater as fighters and actors have long had a symbiotic relationship. It’s been said mankind’s first performance art occurred as ritualistic reenactments of hunts and battles and that overtime these scenes evolved into more sophisticated art forms like fencing, capoeira or WWE wrestling, all of which combine the illusion of combat with more performative demands. Since the early beginnings, the combat coordinator’s role has always been the same, which is, as Zuko says, “to choreograph a story so it can be told after words have failed, to find the plot advanced by the violence, to continue the story with movement.”

In order to effectively communicate without scripted lines, coordinators must assume both the perspective of the audience, figuring out how to progress plot-lines and status-plays in a way that feels real, and of the actors, with whom they are tasked not just with orchestrating, but with keeping safe. And, until recently, “safety” was usually explained and understood rather one dimensionally, simply as a physical demand. Case in point, Zuko has all but memorized a list of “13 things that can go wrong when you actually slap someone.”

1) A fingernail could slice an eyeball.

2) An eardrum could rupture.

3) The jaw could dislocate.

The list goes on.

But in a scene like that from Wisdom From Everything, in which a violent scene is indistinguishable from a sexual one, it’s clear the production isn’t just grappling with the physical effects and consequences of onstage violence, but the psychological ones as well. Still, such considerations are infrequently included in anyone’s job description and rarely discussed among actors or production teams. As Zuko says, it’s probably why actors are notorious for drinking after work.

“It’s interesting because one of the things we actors get taught is how to get into dark and scary places, that’s why we learn breathing techniques and acting techniques, so we can learn to get deep inside of a role,” Zuko says. “But how are we supposed to get back out? That’s not really talked about even though it’s a hell of a lot harder to do.“

But, with the recent swell of Hollywood’s #MeToo movement, mindsets have started to shift, highlighting invisible wounds as much as visible ones. And productions across the country, both on stage and screen, have found themselves dealing directly and intentionally with the emotional side of violence, especially when it comes to sex.

And so, in February 2018, when faced with the violent sex scene in Wisdom From Everything, Local Theater Company added to Zuko’s job description. She is now the “combat and intimacy coordinator,” and it’s a role she is well trained for. In addition to her other skills, Zuko is also a star and curator of Denver and Boulder’s burlesque scene, in which one of her primary responsibilities is to ensure the safety and well-being of people in highly sexualized roles. She eagerly accepted Local’s offer, making Zuko what is believed to be the first and only intimacy coordinator in the state.

“It’s exciting because it’s a radical idea to have actors communicate about what they feel about what’s happening and what they’re doing,” Zuko says. “We tend to talk about theater as a cathartic art for the audience, but we need to remember that the actors orchestrate that catharsis. My job now is to help them identify and maintain an aspect of self-control so that as they go through very intense scenes, they maintain a space in the brain that is not involved, almost like an inner stage manager reminding them about blocking and of what comes next.”

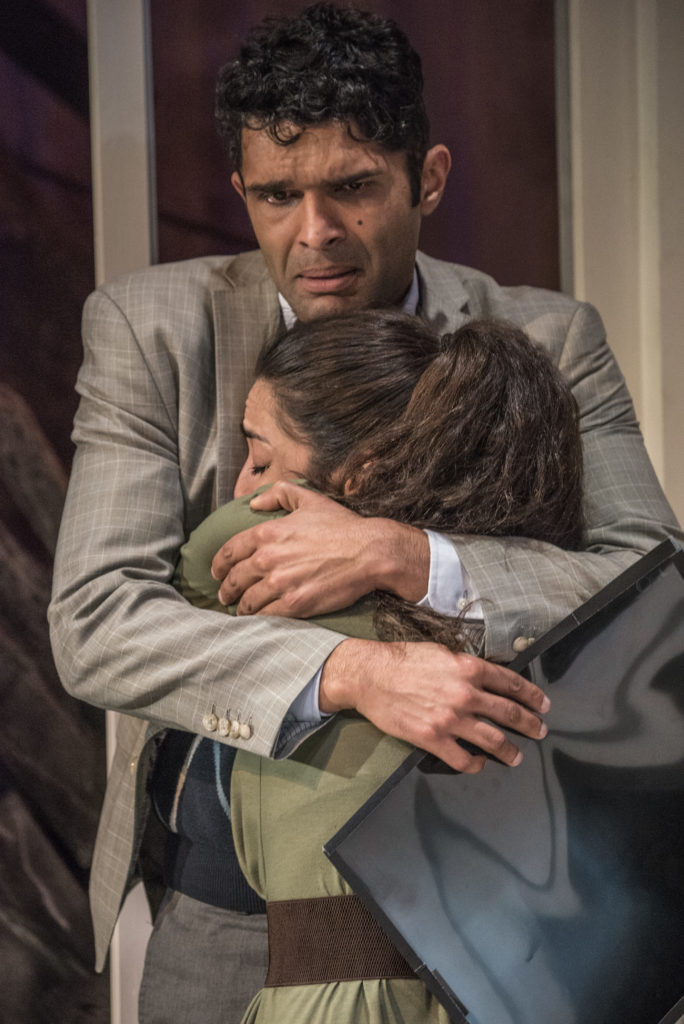

For Wisdom From Everything, Zuko worked with both actors in the violent sex scene to understand how they felt about the act they were being asked to perform, about how it would feel to have loved ones in the audience watching them do it, and how to become comfortable with the scene’s choreography, as one actor forcefully shoved her hand, palm side up, underneath the buttock of the other.

It turns out Zuko isn’t just a pioneer in Colorado, but in the industry at large. In October 2018, seven months after Zuko stepped into her new title, HBO made headlines with the implementation of a new, if not daring, policy requiring the presence of intimacy coordinators on all the company’s ongoing and future productions.

The policy was brought about by actor Emily Meade who, while playing the role of a prostitute on the network’s The Deuce, became concerned with what it meant to feel safe in her work place, particularly as she was asked to perform sex acts on camera.

In her article for Rolling Stone, Breena Keer quotes HBO’s first intimacy coordinator, Alicia Rodis, as saying: “With intimate moments, from kissing to intense sex scenes, it’s been the practice [for directors] to just say, ‘Whatever you’re comfortable with, just go for it.’ But if you’re not giving someone a map or an exit or a voice, just asking actors to roll around and get off on each other, are you asking your actors to do sex work? Or tell a story with their movements?”

For Zuko the transition from combat to intimacy coordination has helped to illuminate the value in both; just like she has seen combat choreography empower a woman who’s never fought before, she is now seeing a person empowered to insist on sexual safety in their workplace in an unprecedented way. Radical as it may feel, Zuko offers a reminder that the basic tenant of combat coordination is the same as intimacy coordination is the same as acting itself:

“When I work on a scene like the one in Wisdom From Everything I am using the exact same principles and practices as I do in a sword fighting scene as I do when I work with middle school kids in an after school Shakespeare club: The most important thing you can master regarding your movement on stage is awareness.”