On July 14, 2015, the interplanetary space probe known as New Horizons flew past Pluto and gave humans the first up-close view of the dwarf planet. Back on planet Earth, the people behind New Horizons celebrated their long-held dream finally coming true.

“It was like you might expect, almost like in a movie,” says Alan Stern, the head of the New Horizons mission. “People were fist-bumping and high-fiving each other, and some were crying and some were jumping up and down. It was an amazing feeling for everyone on the [2,500-person] team.”

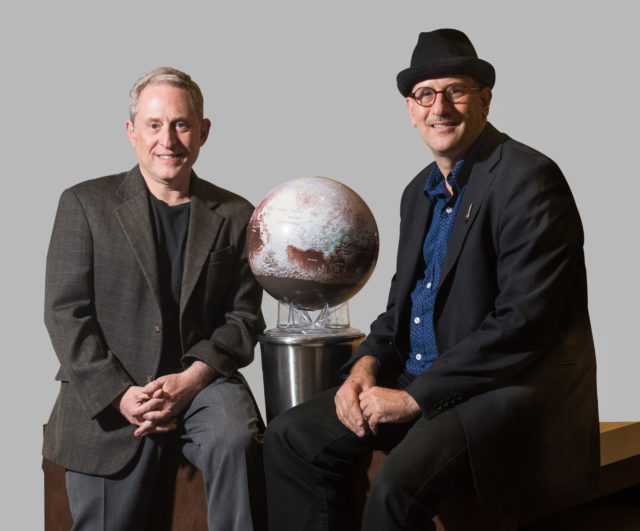

The journey from conception to realization is chronicled in the new book Chasing New Horizons, written by Stern and astrobiologist David Grinspoon. On May 19, Grinspoon and Stern willstop by the Boulder Book Store to talk more about their book and the mission to Pluto.

The early inklings of a trip to Pluto came about in the late ’80s. But it wasn’t until 2001 that Stern and his team were selected. Throughout the process, the New Horizons project was cancelled, put on hold, and even had a computer malfunction only days before it was scheduled to encounter Pluto.

Involved with the probe peripherally, Grinspoon says he was always a longtime fan and cheerleader. He hopes the book provides insights into the reality of space exploration.

“A lot of people think space flight is cool, which it is, and they’ve seen the pictures and they know we got to Pluto,” Grinspoon says. “But they don’t know what it takes, the years and, in this case decades, of struggle to get [a project] to that point where it has the support to build and fly a spacecraft.”

Pluto is approximately 4.67 billion miles from Earth. When constructing New Horizons, the team created a small, lightweight spacecraft that would be able to traverse the solar system.

“This journey is 12,000 times as far away as the Earth’s moon,” Stern says. “We were travelling almost a million miles a day, every day, seven days a week, 52 weeks a year, at record speed, and it took us nine and a half years to travel the distance.”

There was also a tight deadline. The probe needed to launch by 2006 because there was a short window of time where Jupiter would be in the right place to slingshot New Horizons into Pluto’s orbit.

“There was tremendous pressure to get everything built and approved and working and tested,” Grinspoon says. “They couldn’t delay or there wouldn’t have a mission.”

To get funding for any space exploration is a feat in itself, especially considering the number of projects vying for the limited amount of resources at NASA’s disposal. And Grinspoon says the project was met with skepticism.

“Pluto was not that popular,” he says. “Why should we go all that way to study a place if we don’t even know if it’s going be that interesting?”

Thankfully, Pluto provided a wealth of new information, even more than expected.

“Pluto did its part, if you know what I’m saying,” Stern says with a laugh. “When we got there, it didn’t turn out to be one of the typical, run-of-the-mill places of the solar system. It turned out to be a spectacular scientific wonderland.”

Stern lists multiple significant features on Pluto including ice volcanoes, avalanches, Texas-sized glaciers, ancient craters next to new terrain, a complex atmosphere, weather and evidence of water oceans underneath the surface.

Both Grinspoon and Stern say scientists were surprised to discover how active, dynamic and diverse the planet turned out to be.

“We expected a small planet like that, without any heat sources, would be kind of dead and old and battered,” he says. “But in fact, Pluto has areas that are young and vibrant and overturning. That made us go back to the drawing board and re-conceive our theories of how planets work.”

With every new piece of information we learn about the universe, we can better understand our own planet and its origins.

“We can’t understand any one part of it, without understanding all of it,” Grinspoon says. “So it’s filling in the missing pieces in the origin story of our own solar system and helping us become smarter about how planets work.”

And New Horizons’ journey isn’t over. As 2019 dawns, the probe will fly past a small object, known as Ultima Thule, in the Kuiper Belt. Stern calls it a building block of the solar system that will help us learn more about the formation of the planets.

After it passes Ultima Tulle, New Horizons will continue on.

“It’s going to be only the fifth human-made spacecraft ever to leave our solar system,” Grinspoon says. “A little piece of our civilization that will wander the galaxy forever.”

On the Bill: Chasing New Horizons — Alan Stern and David Grinspoon. Saturday, May 19, 5 p.m. Boulder Book Store, 1107 Pearl St., Boulder.