In November 2016, Jose (a pseudonym) found himself at the Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) contract detention facility in Aurora. He had been living in the U.S. since 2002, first in Iowa, where he met his wife, a U.S. citizen, and later in Arizona. The couple has two young daughters together.

Jose had never interacted with federal authorities before. But in July 2016, he was taken into ICE custody after being arrested by local police. A few months later, he was transferred to the Aurora facility because there was no longer enough space in the Arizona detention center where he was being held.

“I was very scared of not seeing my children again and not being able to stay here (in the country),” he says, via an interpreter. “I just sat around thinking about what was going to happen, if they were going to let me stay or not. I didn’t know what to do and I looked for a lawyer but I couldn’t hire one.”

Then, attorneys with Rocky Mountain Immigration Advocacy Network (RMIAN) came to the detention facility, and Jose attended the Legal Orientation Program (LOP), a federally funded information session that aquaints people in civil immigration detention with their rights as they move through immigration court proceedings.

Through LOP, Jose connected with a pro bono lawyer, who explained he could be eligible for deportation relief, given his family situation.

“It was helpful. They explained bond and how I could get out,” Jose says. “I was very thankful because through the lawyer I was able to stay here with my family.”

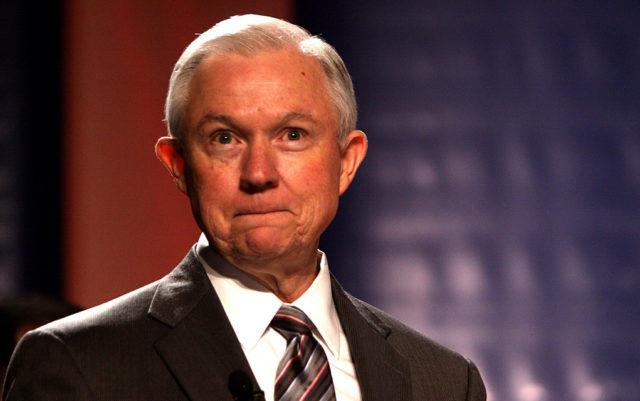

Until Wednesday afternoon, April 25, the program that helped Jose was on life support. Earlier in the month, the Department of Justice announced its intention to suspend funding as of April 30 without any prior warning. But just as suddenly, Attorney General Jeff Sessions reversed his position this week and will allow LOP to remain in place while the program is audited.

That’s good and important news for those who need and administer this vital program.

“It provides what is the fundamental underpinning of our country and our legal system, which is: there should be equal access to justice for everyone,” says Mekela Goehring, executive director of RMIAN. “And there (are) just fundamental fairness considerations in terms of providing people info and the tools to be able to make these decisions.”

Distributed through the Vera Institute of Justice in New York, the federal government allots roughly $8 million a year to 19 different nonprofits around the country, working in 37 immigration detention facilities and serving approximately 53,000 people a year.

“The Department of Justice’s announcement today (April 25) that it will reinstate the Legal Orientation Program is the right and just decision for a program that never should have been threatened in the first place,” Goerhing says. “The relentless advocacy and awareness-raising done by RMIAN’s clients, supporters, staff members, members of the media and elected representatives in Colorado who spoke out to save the Legal Orientation Program showed the necessity and power of this work for individuals ensnared in civil immigration detention.”

LOP funds are dispersed monthly and represent about 20 percent of RMIAN’s annual budget, or a total of $240,000.

The Colorado nonprofit was one of the first six sites to launch pilot LOP projects under President George W. Bush in 2003.

“It was started really as an innovative model to both promote immigration court efficiency as well as provide some really fundamental protections for people in detention who are going through immigration court proceedings,” Goehring says.

Five afternoons a week, RMIAN lawyers and staff experts provide the hour-long legal trainings at the Aurora facility, serving more than 2,000 individuals each year. All of the lawyers working with RMIAN are bilingual in Spanish and English, and have access to telephonic interpretation for people with other language needs. RMIAN also works on an individual basis with detainees, helping them gather appropriate information for their cases.

“The LOP has really been a lifeline for the vast majority of individuals going through these proceedings,” Goehring says. “The information and the value of that information on the individuals who are in detention really can’t be overstated. Because for the majority of them, had they not had the opportunity to talk to a RMIAN attorney and get this information, they may have simply accepted a deportation order without having access to these legal protections that operate under our existing immigration law.”

Through the program, RMIAN lawyers have helped victims of crime and human trafficking avert deportation, as well as people with legal permanent residency and other factors, like asylum and humanitarian protections, which allow them to stay under existing immigration law. They’ve also helped people realize when they don’t have a case and there is no legal remedy for them to remain in the country. In certain cases, RMIAN also connects people in detention with pro bono lawyers who represent them in court.

Classified as civil cases, and not criminal, immigrants facing deportation don’t have the right to a court appointed attorney, and in many cases LOP provides the only legal aid they may ever receive. Goehring says 91 percent of people at the Aurora facility will not have an attorney heading into their hearings.

“Immigration law cases are some of the most complex legal proceedings both procedurally and substantively,” Goehring says. “The types of cases that individuals are fighting for and litigating are some of the highest stakes cases that an individual may encounter in their life. A loss may mean deportation or banishment from a country where they’ve lived their entire life; it may mean a return to a country that they fled because of persecution or other harm; It may mean separation from family members.”

Immigration courts are severely backlogged around the country, and Colorado has the longest wait-time in the nation at an average of 1,058 days — almost three years. A 2012 review of the LOP found the program saved the federal government almost $18 million a year, since detainees who went through the program typically spent an average of six fewer days in detention. Additionally, a 2017 case study of the immigration court system commissioned by the federal government found that better access to attorneys helps shorten delays in the court system and the federal government should consider expanding LOP in response.

In an email to Boulder Weekly prior to Session’s April 25 announcement, a DOJ official said: “LOP has been paused in order to undertake a review of the program, which has not been completed for more than five years. As this program costs taxpayers $6 million per year, we believe that audits of this nature should occur more frequently than every half of a decade.”

Despite the cost-reduction facts and Sessions’ promise to slash the backlog in half by 2020, the DOJ could still suspend the program following the audit.

Colorado legislators were quick to criticize the original decision to suspend the program, calling on the DOJ to conduct its evaluation while continuing to fund the LOP. In a letter to Sessions, Rep. Jared Polis states, “To suspend this program under the auspices of conducting further evaluation is short-sighted and would destroy an indisputably effective program that has been successfully operating for the last 15 years.”

On April 18, Colorado Senator Michael Bennet signed onto a letter to the DOJ with 21 other senators demanding funding for LOP to remain in place.

A spokesperson for the Senator says, “[Bennet] believes that suspending the Legal Orientation Program will undermine due process for Coloradans who otherwise don’t have access to essential information as they prepare to navigate the immigration court system. While he supports oversight of the program so that it continues to operate efficiently, he doesn’t believe it has to be suspended while the review is ongoing.”

Following its announced suspension, Bennet called on the DOJ to restart the program that he claims has been proven to save taxpayer money, while also guaranteeing due process for a vulnerable sector of the population and helping to reduce the backlogs in immigration court.

It appears these congressional pleas have had an impact on Sessions and the DOJ, at least for now.

In a Senate subcomittee meeting on April 25, Sessions explained his decision to keep LOP intact: “I recognize, however, that the Committee has spoken on this matter, and, out of deference to the Committee, I have ordered there be no pause while that review is conducted. I look forward to evaluating the findings and will be in communication with the Committee when they are available.”

Like many things during the Trump administration, the future of the program, the nonprofits who administer it and the people in detention who so badly need it, is uncertain.

“I think it goes without saying, that if you completely shut this program down, a program that has been operating for the last 15 years as a national network, to even think about restarting it is going to require such a huge and significant amount of resources,” Goehring says. “We must do everything we can to ensure this vital lifeline continues well into the future.”

RMIAN is currently strategizing what it will do to keep providing legal services at the Aurora facilities should LOP funding ultimately be suspended.

It has been one year since Jose was released from immigration detention and was reunited with his family in Arizona. After attending LOP at the Aurora facility, and with the help of a pro bono attorney, Jose was able to prove that his deportation would cause extreme and unusual hardship to a family member who is a citizen, since his wife is disabled and he is the primary caregiver for both her and their daughters.

“It would have been very difficult for me to know what to do,” without the lawyer’s help, Jose says. “I want to thank [RMIAN] for helping me with my case.”

Now a lawful permanent resident, Jose walks through life with more confidence, no longer afraid to leave the house for fear of getting picked up by immigration officials. He is, however, troubled by the potential future loss of the Legal Orientation Program and what that would mean for other immigrants.

“It’s not right because there are many people who are detained that need those services,” he says. “It’s not right for the government to take away the help that the people need, the same help that I got.”