In 2012, the world shook with the news that Trayvon Martin, a 17-year-old unarmed African American boy, was shot and killed. He wasn’t the first unarmed African American killed and/or murdered, and the deaths of Eric Garner, Michael Brown and Sandra Bland proved Martin certainly wouldn’t be the last.

Frustrated by the growing list of deaths and continued police brutality in the country, artist Michael Dixon turned to the canvas to make sense of this complex and disconcerting problem.

“My work really deals with racial identity in this country,” Dixon says. “I’m thinking about these killings and how to process that. [Moreover], I’m thinking about blackness and the value of black bodies in America, or lack thereof.”

The end result is a series entitled The More Things Change, the More They Stay the Same, a collection of self-portraits in which Dixon uses props that carry loaded imagery. These include a monkey mask and a Sambo doll.

“This particular doll I have is old and it’s broken, but it’s smiling. It’s an American caricature of blackness,” Dixon says. “I use that doll very intentionally because it becomes this metaphor for blackness.”

He uses self-portraiture and these symbols as a way to insert himself into the broader narrative of what’s happening in America.

“There’s a part of this particular work that is very intuitive. When I go into it, I don’t have all the answers per se, but I’m including myself in the conversation,” he says.

Dixon also struggles to navigate these complex issues as a biracial man. With a white mother and an African American father, Dixon uses his art to express his layered identity.

“The law of the land tells me I’m black. History tells me I’m black. I identify as black or biracial,” he says. “The overarching thread throughout my work is talking about this space of being biracial — not quite fitting in a white context, and not quite fitting in a black context. My work really explores this kind of middle space, where you’re constantly negotiating your identity.”

As a light-skinned black man, Dixon says he’s sometimes mistaken for white. And throughout the years, depending on his hairstyle — shaved, afro, dreadlocks — he’s received different treatment from society.

“In my experience, what happens is,when people think you’re white, they tend to say racist shit assuming that you’re on board,” he says. “It’s hurtful because a large part of my identity is wrapped up in being a black person of color. But I do think my lightness has aided me in terms of when I get pulled over by cops and situations like that. If I were darker those kinds of encounters could have been very different.

“My lightness allows me to have this ambiguity that allows me to walk through the world and mostly go where I want,” he continues. “The detriment is, depending on people assuming who I am, I become hurt by what people say or assume. While my body is maybe protected, my emotional state may not be protected.”

Dixon says he’s lost faith in the judicial system and justice in general, as he’s followed continued police brutality. He wants his work to show that he’s involved in the conversation, even if he can’t solve the underlying problems.

“I don’t proclaim to have any answers, but hopefully the work will ask some questions,” he says.

Dixon’s self-portraits are currently displayed as part of the exhibit Divided: Race and Identity in Modern America, a collection of work exploring similar themes, including sculptures by Michael Brohman. A college-level art teacher for over two decades, some of Brohman’s inspiration for his work comes from the conversations he hears from his students, specifically in how students view others who are different from them.

“Even now with so much awareness around these problems, because it doesn’t necessarily happen to them, [some students] don’t see it. They don’t acknowledge it. They’re not aware or they’re indifferent to the fact that discrimination, racism, harassment, disenfranchisement happens to other groups of people,” Brohman says. “They think it just doesn’t exist.”

Through sculpture, Brohman looks at the systemic and institutional roots of racism. Many of his works feature columns, which he says represent systems of government and public edifices that society exalts. He questions these establishments and who controls them — statistically mostly white men.

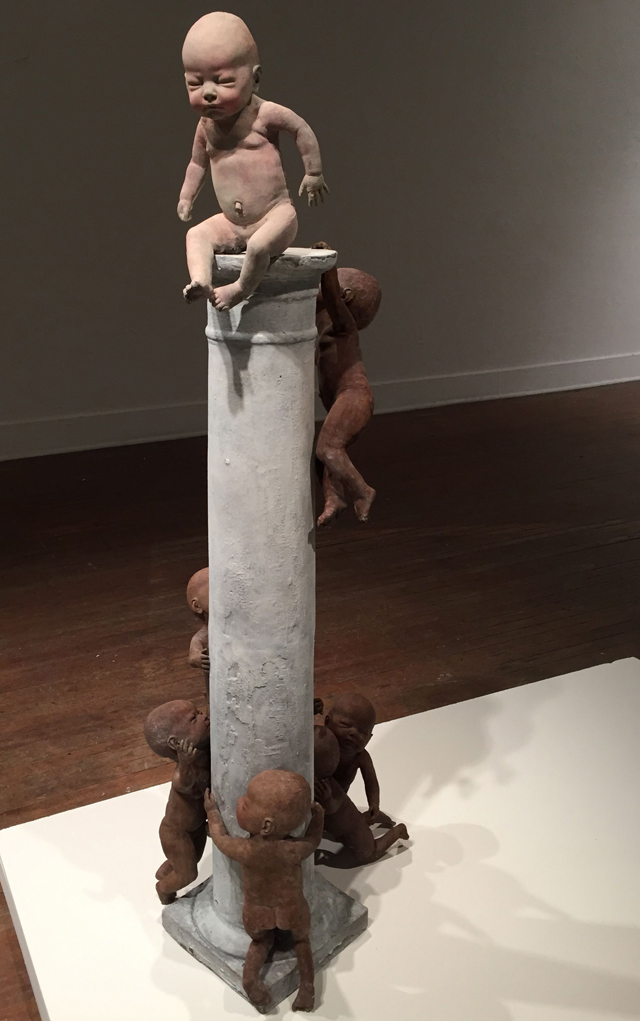

In “Tipping Point,” two columns tilt to the side suggesting a collapse is imminent. In “Cutting Through History,” a column stands tall but its bottom shows a significant portion hacked away. In “Power,” a column is surrounded by baby dolls. At the top of the column sits a white baby, oblivious to the others around him, a black baby climbs the column, reaching out and gripping to the ledge where the white baby sits, while another group of black babies attempt to climb to the top or maybe push the column down all together.

Brohman says his works focus on moments in time. He presents a frozen narrative, and invites the viewer to complete the story — how do they want it to end? Or how don’t they want it to end?

“Does the white baby turn around and push the other baby off? Does it kick the others off the pedestal?” he asks. “Do the other ones push the column down, destroying the system? Or do they work together to get to the top and share the pedestal? Those are all the unanswered questions.”

As a Caucasian artist featured in Divided, Brohman is quick to acknowledge his privilege, something he wishes more people would do and then use to contribute to the dialogue.

“I’m very aware of not trying to represent myself as knowing how other people who have faced discrimination feel,” he says. “I’m not trying to put myself in their position. I’m looking at how the systems of government and law enable one group to be in power and/or enable one group to have more control over others.”

Brohman’s art boils down to one simple desire.

“Is [my art] solving the great problem? No,” he says. “Is it making more of an awareness, more of an understanding, more empathy that may enact a little bit of change and get people involved somehow? Hopefully. I just want people to give a damn.

“I want people to look at the work and look at it positively or negatively,” he continues. “To see how they are an active participant of our system and how they enact change or keep the system from changing.”

For some, the concept of change is loaded. The title for Dixon’s series, The More Things Change, the More They Stay the Same, came from reading historical texts and speeches from black leaders.

“Frederick Douglass was giving these speeches in the late 1800s, W. E. B. Du Bois in the early 1900s, Malcolm X and MLK were in the ’50s and ’60s — and a lot of the themes they’re talking about could have been written today,” he says. “It was really horrifying and interesting that these themes are as relevant today as they were 100 years ago, or over 100 years ago.”

Also throughout his research, Dixon read books like The New Jim Crow, by Michelle Alexander, who looks at the connection between slavery, Jim Crow laws and mass incarceration. While many may think the tragedies of racism are problems of the past, its roots are so systematically embedded that Dixon questions if the world is different at all.

“In my mind, historically you’ve always had this minority of wealthy elite, the 1-percenters if you will, and this whole idea of whiteness and race used as something to divide and conquer the people who are not wealthy, which is most of us,” Dixon says. “So the fact that you have impoverished white people holding onto the concept of race and somehow that elevates them, it’s like the oldest trick in the book that’s played over and over again…

“My feelings about America today, we can argue that it’s much better for a lot of people — and it’s definitely better,” he continues. “But in a lot of ways it’s exactly the same.”

Dixon hopes his work, and exhibits like Divided create the opportunity for honest conversation, both about the historical and contemporary world. Dialogue serves as an agent for change.

“So it’s always my intention with my work to create opportunity for conversations to happen around race and identity,” he says. “If we can’t have honest conversations, we can’t move forward.”

On the Bill: Divided: Race and Identity in Modern America. Dairy Arts Center, 2590 Walnut St., Boulder, tickets.thedairy.org. Through March 4.