I asked our driver what he’d recently heard about the canal. He responded, “We’ve been hearing about the canal for 50 years.”

We were driving from the city of Granada up to Mombacho Volcano for a day of hiking in November 2017. It was just a few weeks shy of official tourist season and so the hotels, drivers and restaurants were uncrowded and less expensive. I was traveling with my partner, Catherine, and we spent three weeks in Nicaragua, roughly following the route of the proposed canal. It was an unusual environmental-writer adventure for me because I didn’t ask too many questions of the people I met. I usually question everyone to get a good story, but in Nicaragua, the government is not fond of outsiders (or its own citizens) asking hard questions about the canal or anything controversial in Nicaragua. So, I gathered as much information as possible and stayed relatively quiet while in the country.

I spent several days in Granada, several on the island of Ometepe in the massive Lake Nicaragua, several more days on the Pacific coast and then a final few days over in eastern Nicaragua in the rainforest. All of these areas would be completely bisected and devastated if the massive canal is built. Many news reports have called the proposed canal the “biggest infrastructure project in world history.” I would add that it would likely be the most environmentally destructive project in world history.

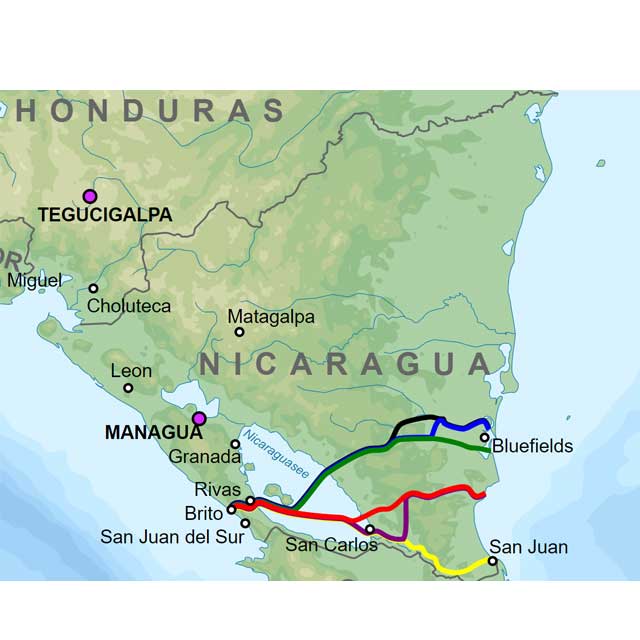

For over a hundred years, some people in Nicaragua have dreamed of building a massive shipping canal across the country from the Caribbean Sea to the Pacific Ocean. The dream, which many people call a “scheme,” is to build a canal bigger than the Panama Canal (three times as long and twice as wide) that could transport massive container ships, tourist cruise ships and supertankers carrying oil and fracked gas. They call the proposed waterway the “Interoceanic Canal,” and it would carve through near-pristine rivers and rainforest on the Caribbean side of Nicaragua, travel through the massive Lake Nicaragua, and then carve a path over to the Pacific Ocean. The environmental destruction has caught the eye of many international environmental groups and journalists because it would destroy 400,000 hectares of rainforest and wetlands as well as imperil more than 20 already-endangered species. Further, the project would displace up to 120,000 people.

The dream/scheme got a lot of legs in 2015 when Nicaraguan President, Daniel Ortega, signed an extremely controversial agreement to build it with a Chinese billionaire named Wang Jing, owner of HKND Group. The agreement bypassed and gutted various Nicaraguan laws, gave rights and profits away to Wang Jing, and was roundly protested by thousands of Nicaraguan citizens and the international media. However, the canal has recently been put on hold because Mr. Jing lost a lot of money in the Hong Kong stock market crash of 2015, and because his business dealings have increasingly come under legal scrutiny. A November 2017 article in Bloomberg called Mr. Jing the “Canal Madman” and questioned if the project would ever be built.

The city of Granada sits on the shore of Lake Nicaragua where it is a leisurely 10-minute stroll from the quaint, colonial town square down to the dock along the lake. There’s a few dozen small hotels in Granada, all less than three stories tall, with most of them having less than 20 rooms. The restaurants, too, are currently designed to meet the needs of a small number of tourists who travel here in cars or buses — maybe several hundred people a day during the height of the tourist season in December and January. As we walked down the street in November, the dock on the lake was almost completely unused, and the closer you get to the lake, the restaurants and shops dwindled and decayed.

Imagine what it would be like if daily, or twice-daily, 5,000-person cruise ships pulled up to that dock and those tourists unloaded their culture, money and tastes into Granada — that’s one of the scenarios the government has put forward in support of the canal. Even though Granada is already a tourist town, the cultural and environmental carnage would be dramatic.

South of Granada in Lake Nicaragua sits the island of Ometepe, which is stunningly undeveloped and uncrowded. In the several days we were there, we paddled around the island in a kayak and stared intensely across the massive, lonely lake. Lake Nicaragua is huge — over 3,000 square miles — and is the largest lake in Central America and the 19th largest in the world. It’s also relatively shallow and would have to be dredged and deepened for large ships if the canal were built. Over four days, I saw maybe 10 motorized boats on the lake, and that included the ferries transporting people to and from the island. Another handful of dugout canoes and pangas (small jon boats) were being paddled around by fishermen who threw their hand nets into the water occasionally pulling out fish. The two huge volcanoes that created the island — Concepcion and Maderas — tower overhead like sentries watching the quiet lake.

Imagine a steady stream of container ships, cruise ships and supertankers passing through the lake and stopping on Ometepe. Imagine the pollution from all of that shipping and human traffic, turning the relatively clean lake into a massive shipping canal. It would be comparable to putting an interstate highway down through the Grand Canyon of the Colorado River in the U.S. to give tourists a closer look at the river, and shipping trucks a faster connection to Las Vegas.

The impacts to Ometepe and Lake Nicaragua might be even less severe than the impacts to the near-pristine rainforest on the Caribbean side of the country that the canal would need to carve through. To get a taste of the rainforest, we traveled down to San Carlos and took a boat down the San Juan River for 40 kilometers to the town of El Castillo. While in Castillo, we took a guided hike and canoe trip through the nearby rainforest preserve.

The jungle was amazing. Three types of monkeys, parrots, sloths, caiman, endless butterflies, tiny poisonous frogs and huge flocks of cormorants surrounded us in the jungle and along the river. With a bilingual guide, we tasted medicinal plants, watched a sloth slither up a tree and listened to parrots screeching in the canopy overhead. After our hike, we paddled a canoe almost silently up the Rio Bartola, a tributary of the San Juan River. As we paddled farther up the river, the water got clearer and we swam in the cool stream to wash off the sweat of the jungle hike.

To get through the rainforest and up one of the rivers, the proposed canal would have to build a series of locks and dams, creating huge new reservoirs, digging massive scars across the landscape and deeply dredging the rivers and wetlands. The environmental devastation — as well as to the communities of people living in the rainforest — would be catastrophic.

The final leg of the canal would have to bisect the landscape between Lake Nicaragua and the Pacific Ocean. The coastline north of the backpacker-tourist town of San Juan Del Sur is quiet and sleepy, scattered with tiny surfer camps and local villages. The canal would enter the Pacific Ocean at the village of Brito, which is a tiny fishing village with a few scattered boats and surfer hostels. A developer is proposing to build a massive airport near Brito and other investors have eyed the area for larger-scale tourism if the canal is built, both of which would dramatically alter the landscape, economy and environment.

As we drove along the coast from San Juan Del Sur up through Brito and up to Playa Gigante, we saw signs about the proposed airport and a smattering of wannabe development. Still, the tiny surfer camps and backpacker hostels seemed oblivious to the idea that the massive canal and mega-tourism could be coming. The Pacific Ocean was relatively pristine, the sun blazing and the surf pounding with not one ship in site when we were there.

Outcry about the canal inside of Nicaragua has been large and has included protests and marches in several parts of the country. The government has responded aggressively against the protests — news reports of harassment and intimidation against human rights and environmental groups is rampant. Amnesty International has called the government’s response a “campaign of harassment and persecution” against communities opposed to the canal.

Outside of Nicaragua, the international media and various activist organizations have also railed against the canal. One of the most outspoken opponents of the project has been Bianca Jagger, who is a native Nicaraguan and an international human and environmental rights activist (and former wife of Mick Jagger). Ms. Jagger has pounded against the project in the media and on her facebook page for the Bianca Jagger Human Rights Foundation. In August of 2017, she spoke to The Guardian about the canal and said it was, “…an insane project that would cause harm to the people of Nicaragua, irreparable damage to our water sources, to our rainforests, to our environment. If allowed to go ahead, it will be an environmental crime.”

Because of HKND Group’s financial failings in the Hong Kong stock market crash, the canal project has been dormant for the last two years. As of this writing, practically nothing has been constructed or accomplished and the Nicaraguan government has stopped talking about it. Some news reports have called the canal “on hold;” others have said it’s “ended.”

The dream of the canal, however, lives on. If you want to see Nicaragua in its wilder, protected state, go now, and you will see this beautiful country as well as why this canal should never be built.

Gary Wockner, PhD, is an international environmental activist and writer based in Fort Collins. He is author of the 2016 book River Warrior: Fighting to Protect the World’s Rivers. Contact: [email protected]