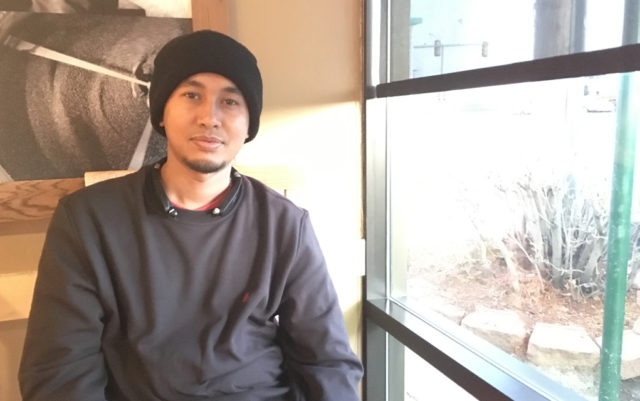

Three hundred and fifty-nine. That’s how many days Shoeb Iqbal has been free in America. If you’re reading this after Jan. 11, 2018, it’s been longer.

The last time we talked to Iqbal (referred to with the pseudonym Mishkat Sarkar in previous reporting) it was early 2016 and he was being held at the U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) Denver Contract Detention Facility in Aurora. At the time, he had been in immigration detention for more than 15 months, starting Nov. 13, 2014 — the day he crossed into the U.S. from Mexico.

After being held for more than two years, Iqbal was released on Jan. 17, 2017, and has been adjusting to life outside of detention in his new home city of Denver since.

“When I got out, everything was like a dream,” Iqbal says.

As previously reported, [Re: “Opposite of America,” Feb. 18, 2016], Iqbal arrived in the U.S. after a harrowing escape from his home country of Bangladesh after experiencing death threats due to his political affiliation with the Bangladesh National Party (BNP), the second largest political party in the country. The BNP had recently lost power to the Awami League and hundreds of its members fled the country due to political unrest.

In 2014, Iqbal came to the U.S. seeking asylum, but was denied because the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) classifies the BNP as an “undesignated terrorist organization,” despite previous joint efforts to combat terrorism with the group. Iqbal denied such claims and filed an appeal. As he awaited a decision, hundreds of Bangladeshis also sat in detention around the country in the same predicament. Many, including Iqbal at the Aurora facility, organized hunger strikes, protesting their prolonged detention.

After we reported Iqbal’s story in 2016, he was transferred to detention centers in Arizona and Louisiana before landing in Alabama at the Etowah County Jail, where immigration detainees are housed with inmates facing criminal charges.

Immigration advocates have long been concerned with conditions at detention facilities, both those housed in public jails and others operated by private prison corporations. A recent DHS report criticizes ICE for “unsafe and unhealthy detention conditions” at facilities across the country, although neither the Aurora nor Etowah facilities were named specifically.

But in Etowah, Iqbal experienced the worst conditions yet. The facility was often put on lockdown, where he would have to stay in his cell for hours, even days, at a time, he says. It cost at least $5 to make a phone call, and it was difficult to stay in touch with his family back home in Bangladesh as well as the friends he had made in Denver.

While there, his mom passed away after suffering a stroke in Bangladesh. He had talked to her the week before and “she was very healthy,” he says. But he didn’t even find out about her passing until a few days later because his family wasn’t able to call him, and due to the cost, he wasn’t able to call home all that often.

“It was hard to hang on to hope,” he says, remembering the loneliness he felt in those days.

Just a few days later, however, the Board of Immigration Appeals ruled in his favor and he was granted asylum.

Iqbal says he’s lucky. He had built a support system in Denver and had immigration lawyers from California and Washington D.C. working on his case. Nationally, only 14 percent of people held in detention have legal counsel, despite the fact that those who do are four times more likely to be released. Of the 15 people or so with whom Iqbal traveled from Bangladesh, all but three were deported, he says.

“They are afraid for the political condition,” Iqbal says of those living in Bangladesh again. The political persecution that led them to flee in the first place is expected to flare up again this year. A general election is set to take place later this fall amid growing fear of unrest as the BNP will once again challenge the ruling Awami League for power.

ICE transferred Iqbal back to Colorado — back to the Aurora detention facility — where he had filed his appeal, before releasing him. On Jan. 17, 2017, he was finally free.

“It was a new world,” Shoeb says.“I was just so grateful to be outside. It was cold, though.”

Still, he made a snowball and threw it at his friends waiting for him. Maria Giordano, Rhoda Whitney and Priscilla Ledbury had all met Iqbal at the Aurora facility, where they often visited him after first hearing his story in 2015.

“The fact that he managed to last two-and-a-half years just going through horrible situations is remarkable,” Ledbury says. “When we’d go visit him, he’d have days when he was really up and days when he was very low.”

But it was all celebration the day he was released last winter. The group went out to dinner, where Iqbal was overwhelmed by the plethora of options on the menu. Walking into the restaurant, Giordano says, Iqbal touched her arm and whispered, “We don’t have to talk through a glass window anymore,” with a smile.

The first 12 days after his release, Iqbal lived at Casa de Paz, a house near the detention center that offers people affected by detention a place to stay, whether they’re recently released or visiting family members currently being held. Then he went to Lutheran Family Services, a refugee and asylee resettlement agency that helped him with food and rental assistance, while he waited for his social security to process. It took a month, but he started working right away, often holding multiple jobs at once. He got his driver’s licence in April, and he now works at DIA in passenger assistance as well as drives for Lyft. But, he says, he wants to go to Emily Griffith Technical College and study accounting or marketing.

“I make my dream come true, day by day, one by one, one step by one step,” he says. “My next dream is I want to get educated, go to college, get a better job. It is hard. But nothing is impossible if you want to do it.”

Slowly, he’s adjusting to life in Colorado.

“It’s a new environment, a new culture. Sometimes people are helpful, sometimes they are not,” he says. “Of course, it’s better than detention — your life is more free.”

“He’s the most self-motivated person you have ever met,” Giordano says. “It’s definitely a rocky ride at times but he’s adapting really well. It’s so nice to have him out and actually spend time with him as a friend.”

Iqbal sees Whitney and Ledbury often and has breakfast with Giordano every Friday. They’ve also visited other detainees at the Aurora facility, including a woman from Mexico who was eventually released.

“There’s really only so much that I can say to somebody who’s in detention, but with Shoeb there, he knew exactly what this woman was going through,” Giordano says. “It was beautiful to watch them have a conversation, in pretty broken English, but that didn’t get in the way of understanding each other and where each other was coming from.”

“Lots of people really don’t know what’s going on in detention,” Iqbal says, or even that there is a detention center in Aurora. Often, when driving for Lyft on Peoria Street, Iqbal will ask his customers if they know the building is a detention center.

“They often say it’s a factory,” he says.

“No, this is not a factory. You need to go and look. It is a jail,” he tells them.

On the one year anniversary of his release, Iqbal will be eligible to apply for permanent residency, and he’s already working on his application. He talks to his family — his father, sister and brother — back in Bangladesh every day, and hopes to be able to bring them to Colorado soon, despite changing national immigration policies that may make it more difficult.

Still, he generally has a positive demeanor, talking brightly about the future and smiling often throughout our conversation. It’s a far cry from the often despondent detainee we talked to on the phone back in 2016.

“I feel like my life is where I want to be,” he says. “I’m pretty much OK. I’m not really happy, but I’m trying to be. I hope, I feel, someday it will all be worth it.”