Curious George made his debut in 1941, brought to life by the husband-and-wife team Hans and Margret Rey. The premise of the book is terrifically simple: George is a monkey and his characteristic curiosity is always getting him into trouble. His ingenuity, though, always gets him out.

Now, more than 75 later, George is an international icon, selling over 75 million books in more than 20 languages, starring in feature-length films and a PBS cartoon, as well as making appearances in homes across the country as a take-home toy, plush and plastic alike. Yes, George the curious monkey is also a cash cow, but his lucrativeness is not superficial. In the modern world, he’s atypical in that he’s not a product of the time, but rather, quite simply, a very special and enduring little monkey.

Perhaps George’s longevity owes to the seductive psychology of the American dream — that you can overcome adversity, even in the face of a seemingly chaotic mix of events that straddle the line between coincidence and fate.

But over the decades George has proved endearing beyond ideations of our own possibilities. He’s an archetypal character that people all across the world hold and treasure. He is a child in an adult’s world, retaining a gusto for life that endures despite very real hardships. That is George’s nature, one that he will never outgrow. And that is why we love him.

His illustrator, Hans Rey, once said about the laborious process of creating each of the eight original Curious George books that the sweat and tears never showed. In that instance he was referring to the yearlong work that went into each story, replete with consultants, publishers and the innumerable drafts that led to the final copy.

But surely he also meant to nod to the story of how the monkey came to be, the story of the Reys themselves, of the very real hardships they went through on their way to claiming the American dream and the whimsical, childlike optimism with which they understood and told their tale.

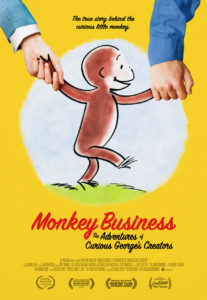

It’s a story told in splendorous detail in the new, feature-length documentary Monkey Business: The Adventures of Curious George’s Creators, by director Ema Ryan Yamazaki. The film explores the extraordinary lives of Hans and Margret Rey, whose creative spirits and resilient attitudes produced a monkey beloved by the world.

The Reys first met in their hometown of Hamburg, Germany, in 1922 at Margret’s 16th birthday party, but it would be more than 10 years until the two would marry. They were young, after all, and the post WWI years were tumultuous. As the world struggled to recollect itself, the two young German Jews were struggling to find themselves, too — Margret always wrestling with her rebellious nature and Hans, the daydreamer, somehow floating through the drudgery of the real world, by way of a 10-year stay in Brazil.

In 1933 the two found each other again (a result of Margret’s blunt tenacity) and married, not out of love but because, as Margret said, they were good for each other. So, quite practically, they started an advertising firm and in 1937, they became accidental children’s book authors when a French publisher suggested they try expanding one of Hans’s cartoons into its own story. But just as their family business was taking off, so was the Third Reich, and the anti-Semitism of the late-1930s threatened to bring it all down.

In June of 1940, the couple was living in Paris as Hitler’s troops approached the city. From the big window in their apartment they could see tanks rumbling at the edges of the town and hear rifle shots. With the trains down and automobiles lying empty on the sides of the roads, the Reys built two bicycles from spare parts and, just 48 hours before the Nazis invaded Paris, they pedaled out of town, two among thousands of refugees fleeing south toward the neutral state of Portugal.

“To hear their surviving friends tell of how the Reys told the story of their great escape you wouldn’t realize the Reys were in the throes of war,” says director Ema Ryan Yamazaki. “They talked about sleeping in barns and eating on the kindness of strangers as if they were on a fantastical vacation, telling their own story with the same curious optimism they imbued in George. What we might call a harrowing journey, they call an adventure — it was a challenge to straddle that line in the film.”

One can try to strip the story of romanticism and say, plainly, that the Reys were two anonymous German Jews carrying Brazilian passports during the Battle of Paris and that the odds were stacked against them.

But, like their little monkey, you can’t separate the whimsy from their true experience. Take, for instance, the time when border officials became suspicious of their German accents but when the Reys showed them pages from the Curious George manuscript, the guards were so taken with the story they allowed the Reys to continue on.

Saved by their own creation — a carefree, irresistibly cute monkey — the Reys eventually made it out of Europe just as the horrors of the Holocaust were beginning to unfold. A few months later, they sailed into the New York harbor and started life anew as sea after sea parted to allow Curious George to spring out of the stuff of their lives.

Until recently, the story of George’s conception was relegated to tales passed down through friends and a few niche reports by scholars of children’s literature. That’s how Yamazaki heard about it, accidentally, by bumping into their longtime housekeeper, Lay Lee One, at a retirement home. But, as soon as Yamazaki, then a 24-year-old filmmaker looking for to make her first feature-length documentary, stumbled upon the story, she recognized its narrative prowess.

“Honestly, I couldn’t believe it wasn’t a movie already,” she says. “For weeks I just looked around the internet trying to find the film that someone else had already made. I really didn’t expect that I’d be the one to make it.”

Yamazaki says she fell in love with the Rey’s story for all of the obvious reasons. Like so many others around the world, she grew up reading Curious George in Japan. And, when she came to America to attend film school at New York University, it was one of the few icons relatable across cultures. (It turns out that, lots of times, children’s characters are actually very culturally specific, she says.) So, when she realized George was just as international as she was, her connection with the little monkey amplified.

“As a filmmaker, I’ve always been interested in what lies between cultures,” she says. “I was really attracted to this story and the more research I did, the more I could relate to what the Reys went through. Somewhere along the line I realized not that I wanted to be like them, but that I was already kind of like them — on my way to becoming a great storyteller, despite the odds, unafraid as I traveled through the world.”

But as excited as she was, deep down Yamazaki wondered if she was really the right one to tell the Rey’s story. Shouldn’t a more experienced director take on such an iconic tale?

“But you know what I realized?” she asks, rhetorically. “If I had waited to start until I knew what I was doing, or until I knew I was the right person to do it, I still wouldn’t have started.”

“But you know what I realized?” she asks, rhetorically. “If I had waited to start until I knew what I was doing, or until I knew I was the right person to do it, I still wouldn’t have started.”

Monkey Business is a movie that, like Curious George, came to be despite the odds. It relied on borrowed equipment, young filmmakers and a behemoth Kickstarter campaign to pull it off, eking out on stollen time and IOUs. But the result is simply wonderful and it’s impossible to see the sweat and tears that made it so.

A menagerie of archival footage, historic stills and original animation, the documentary brings the Reys’ story to life, in precisely the way one would imagine the Reys would have told their own story. And as the movie fades away, you can almost hear the man in the yellow hat telling the Reys he is proud of them and their very curious little monkey.

On the Bill: Monkey Business: the Adventures of Curious George’s Creators. 7 p.m. Friday, Dec. 1, Chautauqua Community House, 900 Baseline Road, Boulder.