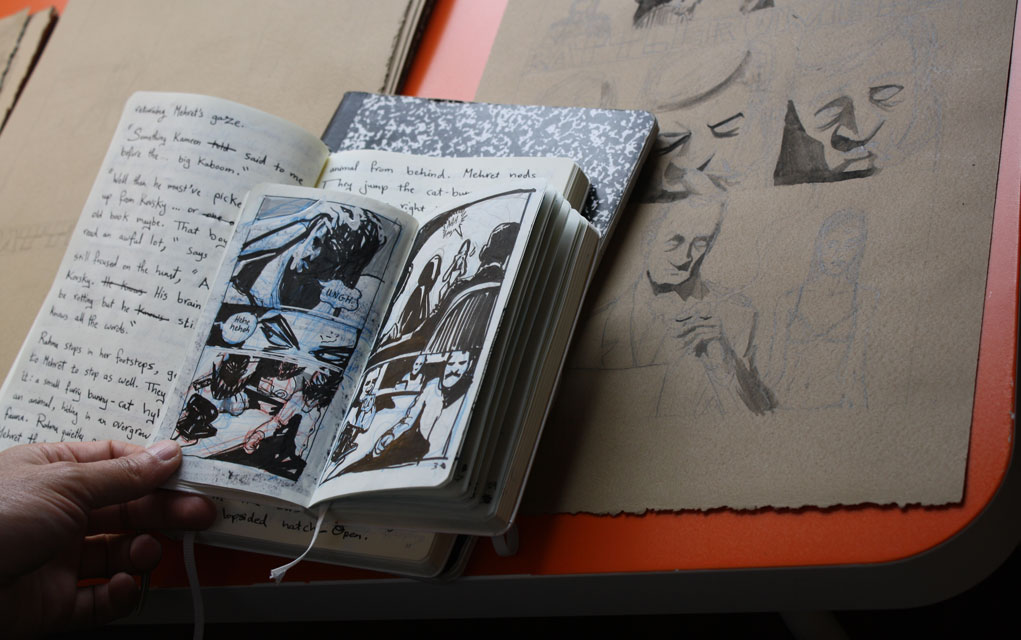

Ganzeer spends most of his time these days sitting at the orange desk in his apartment overlooking Denver’s Cheesman Park. He’s working on a graphic novel, The Solar Grid, which takes place over several thousand years “after the flood,” or AF. Most of the world’s population has migrated to Mars, and Earth has become both a solar factory to power the new world and a landfill to hold all its trash. But a resistance is growing among those left behind, a fictional uprising rooted in the artist’s own experience of revolution.

Ganzeer, a pseudonym, means bicycle chain in Arabic, a metaphor for how the artist hopes his work functions in social spaces — not the source of the motion, but the connection that makes progress possible.

Ganzeer, a pseudonym, means bicycle chain in Arabic, a metaphor for how the artist hopes his work functions in social spaces — not the source of the motion, but the connection that makes progress possible.

“I don’t come up with anything on my own as much as I attempt to connect different ideas together that hopefully enable things to move forward, move it past the certain point that it’s stuck in,” he says.

Although he had gallery exhibits both in Cairo and Europe before the Arab Spring, Ganzeer rose to prominence during the Egyptian Revolution as his street art, along with that of others, drew international attention. His work has largely been labeled protest art or activist art, but it’s a title Ganzeer rejects. Some have called it “contingency art,” which may be more accurate.

The streets were eerily empty in downtown Cairo on Jan. 25, 2011, Ganzeer says. He left a friend’s house with a backpack filled with art supplies, intrigued by the social media reports of a large protest march headed for the Ministry of Interior. As the crowd entered Tahrir Square and clashed with riot police, many bystanders, including Ganzeer, got involved.

“If you were not in Tahrir Square you would not know there was a revolution in the making,” Ganzeer says. “I felt like there needed to be some kind of evidence on the street that something was happening.”

He climbed a billboard featuring an advertisement for then-president Hosni Mubarak’s National Democratic Party in the center of the square and, in white spray paint, wrote what everyone around him was chanting: “Down with Mubarak.” It was a simple but powerful act that elicited cheers from the crowd and created evidence of the event that endured well beyond that day.

From that moment on, Ganzeer threw himself into documenting the revolution through his art. He took the protest out of the square, painting murals around the city.

“I’m not really a protester, because I go to a protest and I feel a little useless,” Ganzeer says. “But when you paint a mural, you create something, and you leave it and it’s still there and people who pass react and it may leave a seed in someone’s head to think about something differently.”

He painted murals of martyrs all over the city and a zombie military officer on top of a pile of skulls. He enlisted volunteer help to put up his famous stencil of a tank facing off with a boy on a bicycle carrying a tray of bread in a popular underpass.

“The idea was to more communicate with the people who do not agree with you as opposed to the people who already agree with you,” Ganzeer says. “If I had wanted to do that then I would have just stayed in the square and done art in the square.”

It’s a philosophy he’s brought with him to the U.S., where he’s living more or less in exile, although that’s an idea he’s still grappling with three years later.

“It’s hard for me to accept that because it’s not something I planned,” he says. “I suppose when you say this person is an artist in exile or an activist in exile there is an impression that person is still active in that context but from a distance. But I’m not.”

He moved to New York City in May 2014; a previously planned visit on a tourist visa turned into a new life as the atmosphere in Egypt became even more hostile toward those speaking out against the military and its leader, and now president of the country, Abdel Fattah el-Sisi. Almost immediately, Ganzeer began working on an exhibit for the Leila Heller Gallery in Chelsea.

“I didn’t like that after being involved in the revolution, that all of a sudden in the museum/gallery context they wanted me to do what I was doing in the streets of Cairo,” Ganzeer says. “I don’t need to persuade a museumgoer in New York to believe in the Egyptian Revolution or that Mubarak or the military should not be in control.”

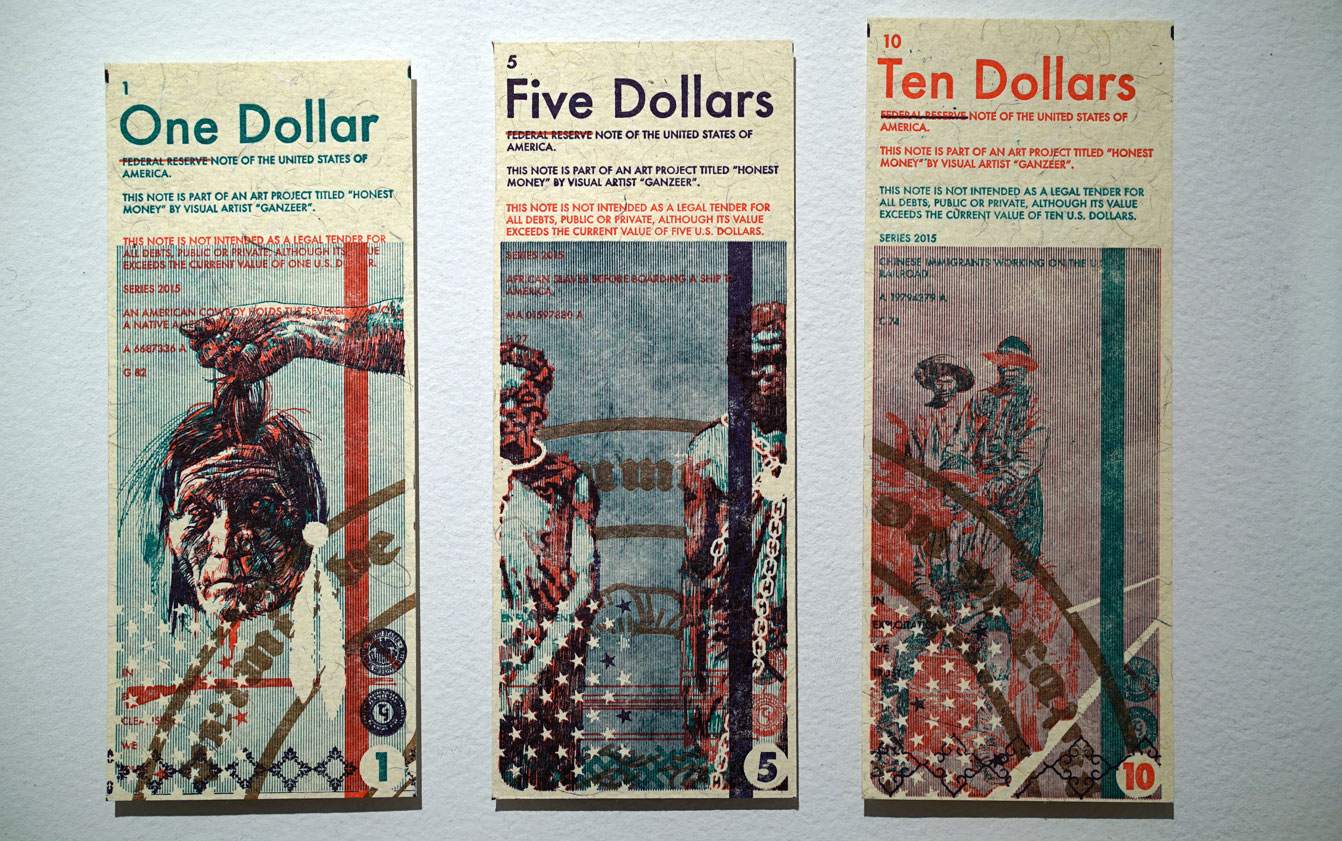

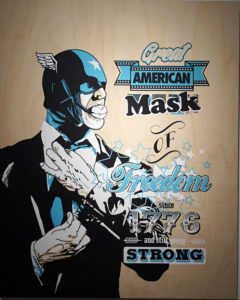

Instead, he took on police brutality and “dark milestones in U.S. history” for his All American exhibition. A man in a business suit, masked and ball-gagged with the words “Great American Mask of Freedom since 1776 and Still Going Strong,” is reminiscent of a popular image he produced in Egypt, which eventually led to his brief arrest. A mock NYPD recruitment poster features a stencil of Eric Garner being strangled on the ground, the contact info “NYPDKILLS.com” and “212-KILLPEOPLE” listed underneath. “Honest money” features U.S. currency with images of beheaded American Indians and slaves in chains.

“A lot of people who came to that exhibition were in shock,” Ganzeer says. “I thought I was stating the obvious.”

He could have shown his work in “some underground anarchist kind of art space,” to a crowd of activists that already agreed with him, he says, but what would be the point?

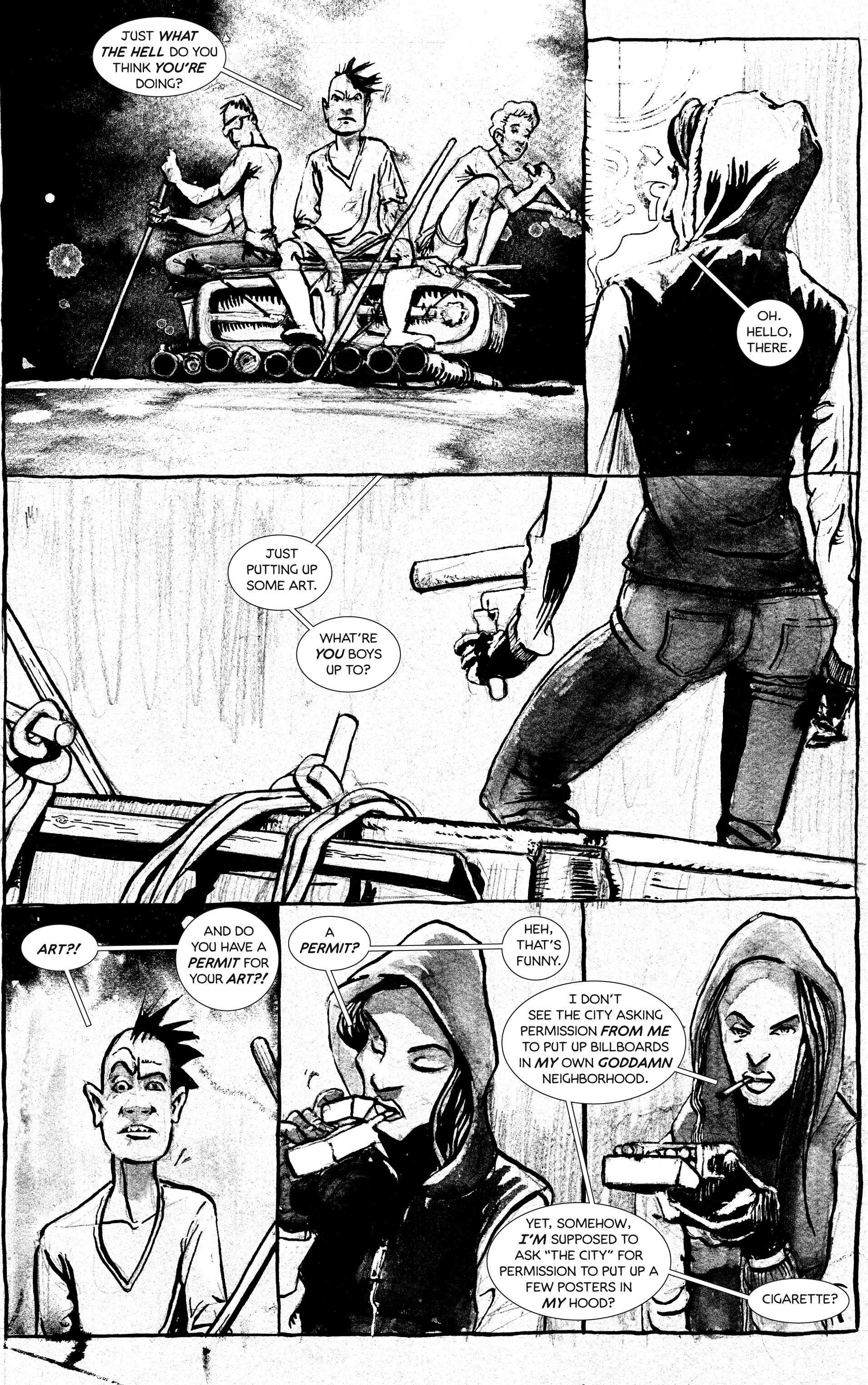

“The point of street art is… that sudden shock,” Ganzeer says. “It’s designed to speak to that person walking down the street who doesn’t make it a point to go out and seek out local art.

“There’s no reason why that approach has to be limited to street art,” he continues. “If you can do it on the street you can do it in any medium, if you can be subversive about what you’re doing.”

It’s something Ganzeer calls concept pop, a blend of the cultural imagery associated with pop art and conceptual art, which esteems ideas more than aesthetics. It challenges both the high-brow world of art galleries and traditional activist art that “is too on the nose.” It speaks to a particular time and place, whether that’s in Cairo during the revolution, or Skid Row in downtown Los Angeles, where Ganzeer lived before moving to Denver a few months ago.

There may be more gallery shows in the future, but for now Ganzeer is singularly focused on The Solar Grid, which he is releasing chapter by chapter with plans to finish by mid-2019.

The novel raises questions of race, nationality and social class, of who gets to go and who stays behind. It “raises questions about hyper-industrialism and hyper-consumerism and interplanetary relationships that is kind of an allegory for international dynamics,” the artist says. “Everything I’m thinking about is making its way into the graphic novel but in a science-fiction context.”

Creating a graphic novel is a laborious process, involving multiple drafts before he begins the final drawings. Ganzeer works methodically page by page, balancing imagery with plot across each spread. He doesn’t employ digital drawing, rather sketching each frame by hand. He then scans the pages, inserting text and adjusting tones on the computer screen. It’s time-consuming and often lonely work, the artist admits.

Creating a graphic novel is a laborious process, involving multiple drafts before he begins the final drawings. Ganzeer works methodically page by page, balancing imagery with plot across each spread. He doesn’t employ digital drawing, rather sketching each frame by hand. He then scans the pages, inserting text and adjusting tones on the computer screen. It’s time-consuming and often lonely work, the artist admits.

A recent Tweet features a meme of a man stretching his arms in front of snow-capped mountains, to which Ganzeer adds, “I left the house today.”

“In the Cairo context I would have to try really hard to be alone to work on stuff and it would be difficult to pull off because everyone was dropping by or calling,” he says. “I was dragged into the Caironess of things, whereas here I’m just at home, at my table, drawing, not really talking to anyone.”

Still, Egypt is never far away and he’s currently working on a section of the novel that takes place in Cairo.

“I want to go back,” he says. “It’s lovely here, but I want to go home.”