We end, I think, at what might be called the standard paradox of the twentieth century: our tools are better than we are, and grow better faster than we do. They suffice to crack the atom, to command the tides. But they do not suffice for the oldest task in human history: to live on a piece of land without spoiling it.” — Aldo Leopold

Visit the Nukemap website and type in “Boulder, CO.” Pick the size of the bomb that you want to drop on the town (20 kilotons) and how you want it to explode (airburst will cause the greatest loss of life). Click “Detonate” to run the simulation. Total radiation radius: 2.21 kilometers. Estimated fatalities: 43,000. Estimated injuries: 35,000.

But here on the Front Range of Colorado such apocalyptic imaginations are not necessary. One need only look at the history of the latent plutonium production facility turned wildlife refuge, Rocky Flats, to grasp the danger of living in the midst of atomic technologies. One would think this should be blatantly apparent to the hundreds of thousands living near what was once the primary nuclear production facility in the country, but it is surprisingly subtle. It was this subtlety that first shocked filmmakers Eric Stewart and Taylor Dunne and that led them to make an experimental film about the West’s nuclear landscape.

A few years back, when Stewart and Dunne both lived in Boulder, they were driving down Highway 93 on their way to Golden and were struck by how entirely unremarkable the land of Rocky Flats appeared. They noted how suburban neighborhoods were casually popping up nearby and how easily the toxic legacy of the land had been forgotten, as the words “wildlife refuge” had replaced the once irascible “Superfund site.” For Stewart, it was a familiar tragedy.

“In my work, I use film and photography as a platform for the landscape to speak for itself,” he says. “In that way, my art approaches activism and refuses to look at nature as a resource or something to be extracted.

“There are two ways to look at the landscape: as beautiful or as a legacy of mining, contamination and genocide. Everywhere that nuclear weapons have touched are totally beautiful places, but I wanted to look behind what we so easily pass over as ‘beautiful.’ This film is about capturing these places and putting them in conversation with the generations of people whose lives have been really, seriously impacted by the nuclear industry.”

Once it’s finished Off Country won’t rely on images of the bomb to shock audiences into fear nor reverence — Stewart and Dunne are not interested in such obvious displays. In fact, they consider such fetishization “dangerous” in how it seeks to turn ordinary men into gods.

“It’s a hyper-inflated rhetoric that emphasizes scientific capability (nuclear weapons) and utopian projection (nuclear power as clean energy) over the very real conditions that nuclear workers endure in the mining and manufacturing of nuclear fuel and the contaminated landscapes that communities have to live around,” he says.

Instead, the film will offer an interrogation of the invisible nature of radiation and the secretive histories of atomic weaponry, offered up in slow spans of the nuclear landscapes of Rocky Flats, Los Alamos and White Sands.

“The story begins with the landscape,” Stewart says. “Our national perception of wilderness has always been one predicated on the elimination of people from the landscape, particularly indigenous people. We like to think that our wilderness is a place where animals are roaming around in some sort of fantasia wonderland and that people are totally disconnected. But this creates a dangerous separation that allows us to look at a place and say it is nothing.”

He goes on to explain that when the military was setting up its nuclear programs, it had a very specific idea of non-utilitarian land as “nothing” and an equally specific idea of non-white people as no one. He says it progressed with the first nuclear tests without any understanding about the communities in central New Mexico, nor about their uses of the land.

“It was a very narrow idea of nothing and no one,” he says. “Forty thousand people lived within 150 miles of the test site and if 40,000 people is no one, well, I have to wonder who is doing this counting. There were hundreds of people that lived as close as eight miles away.”

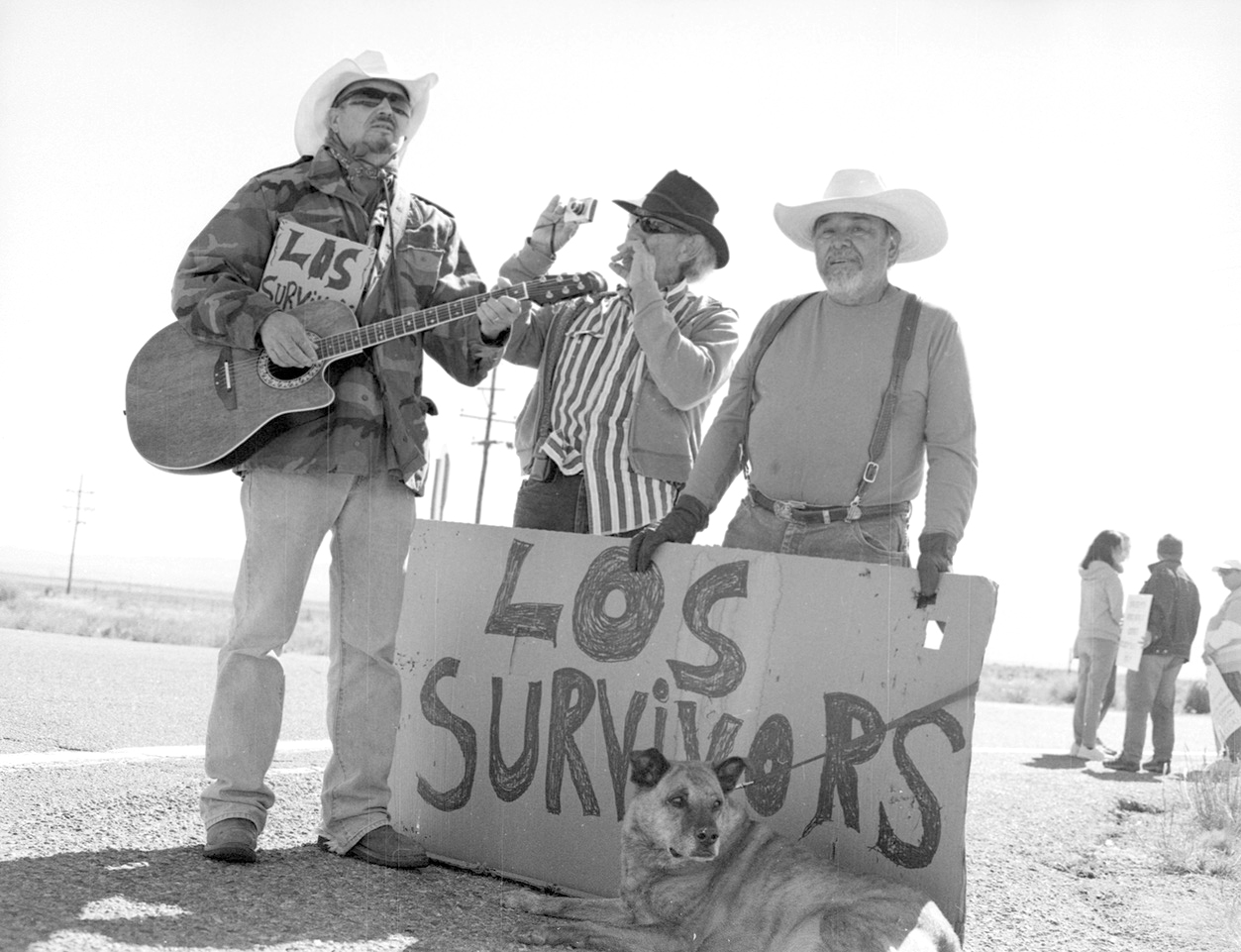

In the environmental ethos, Stewart and Dunne consider people an integral part of the landscape and so the slow shots of still deserts are partnered with quiet testimonies from the people they found on-site.

Perhaps the most prominent characters in their loose narrative are anti-nuclear activists, people who have dedicated their lives and bodies to build a life they believed in. Among the first they spoke to was Boulder’s Dr. Leroy Moore, who abandoned his academic career to advocate for the shutdown and cleanup of Rocky Flats in the 1980s.

Next thing Stewart and Dunne knew, they had spoken to dozens of activists, each with their own harrowing stories of how they used their own lives to draw attention to the human relationship with the planet, and the poisonous properties of nuclear material.

“We talked to one woman who was in nursing school back in the day, and started doing a study about Rocky Flats on her own time. She was so touched by sadness that she was provoked to perform a beautiful backcountry protest in Nevada. She found out where they were going to do an underground test and hiked miles through the desert. When she arrived on ground zero she took off her pack and lay down in the sand.”

By offering these stories as part of the film, Stewart and Dunne are illustrating how advocacy seeks to make action speak louder than individual voices, while questioning how to make atomic wounds visible.

Perhaps the most disheartening of their findings was the discovery of the thriving ancillary industry of nuclear tourism, the central topic of the film’s trailer.

It’s three minutes long, videos of people walking around a chain-link fence, their hands running, clink clink clink, along its surface as they gaze at the empty space at White Sands Missile Range in New Mexico, home to the world’s first nuclear test. There’s footage of people taking selfies near faded photographs of the bomb and of family portraits taken in front of a humbly sized obelisk commemorating the event.

It looks like they are posing in front of nothing but empty space.

Stewart says in working with these images, he came to see nuclear tourism as symbolic of the disconnection between people and landscape that sparked his interest in the project in the first place. Tourism represents the detachment we all feel, not just from the environment, but from our nuclear realities.

“Consider this as opposed to the people who live there still, to the bodies that have been affected by what’s been done in these places, because they truly are a part of the landscape,” he says. “In their absence, I find myself thinking about those still suffering the effects of radiation.”

The film is still in production and Stewart and Dunne are also collecting oral histories as part of a multi-media archive. The filmmakers will be in Nederland on Oct. 28 to speak with community members in Boulder County about the film and archive, share personal experiences, and participate in a dialogue resisting nuclear armament in the 21st century.

“My fantasy is to build a multigenerational grassroots movement to reconcile the legacy of the 20th century while preventing a nuclear disaster in the 21st century,” Stewart says. “This conversation is especially important now, as the government is gearing up for a major investment in nuclear armament, without taking a serious look at how we are still reckoning with the last round.”

On the Bill: Taylor Dunne and Eric Stewart discuss their in-progress documentary, Off Country. 10 a.m. Saturday, Oct. 28, The Art House of Nederland, 171 E. Second St., Nederland. For more information, contact: Taylor Dunne and Eric Stewart 719-587-7069, [email protected]

For more information on the movie, visit www.off-country.com