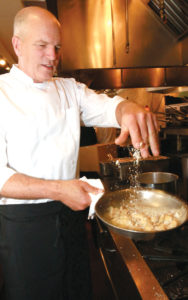

Chef Bradford Heap has a reputation of being hard to work for. That’s according to him at least.

“I’m more of an alienator and more of that old-school hard-ass,” he says. “I’m so intense and so driven, and I want to be successful. I’m such an aggro, type-A freak.

“There’s nothing wrong with me being a driving hard-ass,” he continues, “until it doesn’t work anymore.”

Self-awareness is a virtue Heap has cultivated over time. In conversation, it helps hedge the blunt claims he makes about his role as a leader in Boulder’s food scene and in the national push toward sustainability. In about an hour and a half on the patio of his Niwot restaurant, Colterra (he also runs Boulder’s SALT and Wild Standard), Heap describes himself with words like iconoclast and visionary, and compares his sustainability efforts to Gandhi and Thoreau’s civil disobedience — seconds before or after acknowledging he can sound myopic, egotistical and self-infatuated.

In literally one breath, he’ll say, “I think people are stupid. I don’t think people are informed at all. If they were, my restaurants would be on a wait for seven years.” And in the next, he’ll say, “I just try to have compassion to let people be where they are and not judge them, because the more judgment I have for the outside world, the more judgment I put on myself, and I can’t bear that self-judgment.”

“God, I’m full of shit, aren’t I?” he asks at one point.

For all the talk, it’s undeniable that Heap practices what he preaches. His restaurants are largely GMO-free (for some items like bacon and dairy, costs for non-GMO varieties are still prohibitively high), seasonal, local and increasingly plant-based. Heap, who sees plant-based, organic diets as the only solution to combat climate change long-term, says chefs play an outsized role in leading that food shift.

“I’m not a fucking scientist, I don’t know this shit,” he says. “But guess who’s in charge of trying to steer the ethical and moral boat in America as far as the food system goes? It’s the chefs. I don’t see anybody else doing it. Everybody else is, ‘Can you stuff a few more hundred dollar bills up my butt? I’m not quite full yet.’”

Boulder presents an opportunity to provide a case study for the rest of the country to emulate, Heap says. If meat and produce can be raised responsibly and locally and bought on such a large scale that prices become reasonable at farms, markets and restaurants, then the model can sustain itself. Heap, as a leader in the local food scene, thus sees himself as a shepherd for the national movement.

“I’m a rich, white dude from Boulder, Colorado, I get it,” Heap says. “It’s much different for a lot of other people. They can’t pay attention to it, but somebody’s got to pay attention to it and maybe the intellectual class in Boulder is going to be the first class that can show that this can be done and the benefits of doing it this way, and then it’s got to change for everybody. Then there will be enough people, hopefully, supporting this way of being and boycotting Monsanto and saying, ‘We want healthy food, we deserve healthy food, and fuck you, we’re not going to do what you tell us, motherfucker.’”

That requires responsibility not just for chefs, Heap says, but for consumers. Grass-fed beef might taste gamey, produce may look weird, foods won’t be available year-round, and yes, some things will be out of your price range.

“Is it a socioeconomic luxury? Yeah. And if you can’t afford grass-finished beef and you can’t afford the good shit, buy more vegetables. Go plant-based. There’s no excuse,” he says.

After sharing an analogy that compares forcing terminally-ill people in America to suffer without assisted suicide to the life of animals on factory farms, which are forced to live in cages their entire lives, Heap says, “people get very uncomfortable talking to me about” where their food comes from. “I do this with everybody. It’s not a marketing strategy,” he adds.

No doubt Heap’s passion is authentic. The question, though, is why. So often the conversation around sustainability is about eating well and supporting local farmers. There’s a rah-rah atmosphere that surrounds most discussions. With Heap, though, there’s urgency, a feeling that he’s grabbing you with two hands on either side of your face and shaking, as if you were a good friend in a bad relationship.

“I was born for a reason,” he says. “My whole life has made me tough enough to do what I’m trying to do.”

At 16, Heap dropped out of high school in Boulder and moved to Aspen, where he lived in a van.

“I couldn’t take my dad yelling at me at 3 in the morning saying I was the problem and I was running wild,” Heap says. “Pinning him underneath the piano was a low point for me in my life because he wouldn’t leave me alone.”

Heap says his father was an alcoholic and his mother was “checked out.” His brothers, he says, were abusive.

“The only thing I learned in my childhood was if I wanted to be safe that I needed to be scarier than anybody else in the house,” Heap says. “My brothers would be fucking with me long enough to where I just couldn’t take it anymore and I had to fly off the handle and chase them around with a golf club, throw darts at them, whatever. … Putting a steak knife to ’em, saying, ‘I’m gonna fucking kill you,’ and I’m 10. Or, I don’t know how old I was. It was kind of a blur.”

Heap’s father, about a decade after moving out, paid for him to attend the Culinary Institute of America. Heap says his childhood also prepared him to go to France, where he didn’t know the language (or anyone), to work in a kitchen and be yelled at. All of it, he says, childhood to culinary school to trial by kitchen fire, prepared him to fight for sustainability with passion.

“The whole thing prepared me … to fight a bigger monster; the bigger monster being our food system,” Heap says. “I didn’t know that’s what I was being prepared for. I know I sound like a total Boulder hippie, but … I’ve totally given up on the hope and thought that my path should be anything different than what it is.

“It’s hard to bridge the gap from how you were raised to how you know it should be, and to stay there. Because I kind of revert back like muscle memory.”

Even if the pressures cause him or his emotions to stray, Heap is aware of his path, baring plainly and unapologetically, even cheerfully, his (and others’) faults and successes. Spiritual work has helped him recognize that path. As did the recent passing of his father-in-law, a three-star Air Force general whom Heap called “one of my best friends,” and who, at the funeral, Heap heard described as someone who “brought people in and built them up.” For the self-proclaimed hard-ass chef with a rough childhood, that was an epiphany.

“I need to build people up,” he says. “Everybody’s so hard on themselves, including me. And everybody’s scared. And everybody’s doing the best they can.”

It’s those personal lessons, and the intimate way in which they were learned, that drives Heap toward sustainability. Having kids personalized the effort and put a face on the generation that will ultimately reap the rewards, or failures, of the movement. In that generation, Heap says, there is hope. But it’ll come down to choices.

“Do we continue to do what we were taught,” Heap asks, “or do we evolve to do better?”