The fight to diversify the environmental movement has many battlefields and you cannot liberate them at the same time,” says Irene Vilar, founder of the three-day Americas Latino EcoFestival (ALEF) taking place in Denver Sept. 15-17.

When Vilar started the ALEF in 2013, the first fight was to rewrite the environmental activism narrative, to include Latinos in the conversation and provide a place for them at the table. While the first year was about “screaming really loud,” Vilar says, now the festival has a more focused and strategic vision.

“We kind of found ourselves. We told the story, we created the niche,” she says. “Now let’s leverage this coalition we’ve been nurturing and use it to advance the call to actions that are primary.”

In its fifth year, the festival brings together top Latino environmental activists, attorneys, artists, writers, musicians, policy advocates, filmmakers and others to discuss the most pressing environmental issues, celebrate the achievements of people in the community and engage the next generation in issues of environmental justice around the globe.

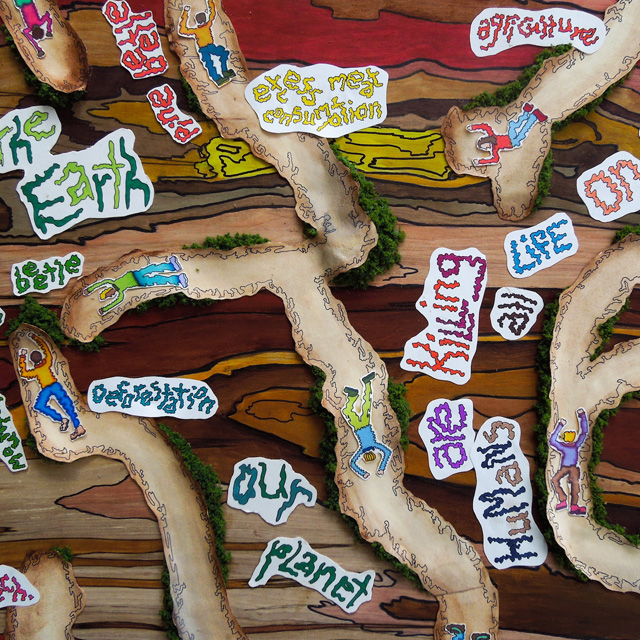

Part of the problem, as Vilar sees it, is that the environmental debate has been relegated primarily to scientists and statisticians, rather than including the voices of those more focused on arts and culture who can draw people in on an emotional level that calls people to action. As a project of the nonprofit Americas for Conservation and the Arts, ALEF has always focused on arts and culture in the environmental movement. But now, Vilar says, it’s the next battlefield so to speak.

“The environmental movement in this country has been very, very dry,” Vilar says. “It has been easier to drive campaigns with numbers, with cautionary tales of catastrophe. But a lot of our communities just blank out. It doesn’t mean anything.”

Connecting the environmental justice movement to culture on the other hand, elicits a different response in people, she says. It offers them not only a way to unify behind the cause but engage in the process as well.

“Culture is your emotional home,” she says. “So strategically speaking, anything anchored in emotions is going to resonate more.”

It is a strategy that Vilar claims Latinos are perfectly poised to implement.

“We have this incredible history of using arts and culture to advance resistance,” she continues. From the rise of graffiti as a form of resistance to the protest songs that define some of Latin America’s most famous musicians, Latinos have often moved environmental justice forward. Plus, she says, there’s a high percentage of Latin American diplomats who are artists. Take for example — the honored guest at this year’s festival — Mexican poet, environmentalist and diplomat Homero Aridjis.

The publishing arm of Americas for Conservation and the Arts, MV Press, is releasing Aridjis’ memoirs for the first time in English this fall. Entitled News of the Earth, the book documents “how an incredible, environmental charismatic leader of Latin America basically leveraged arts and culture to launch a whole movement of environmental advocacy,” Vilar says.

“Part of the problem of the Latino Environmental movement is that we’ve lacked that documentation piece,” she continues. “That’s part of the homework that the festival set out to do five years ago, to create a space to meet up with this leadership, network, stop working in silos and to start documenting these histories.”

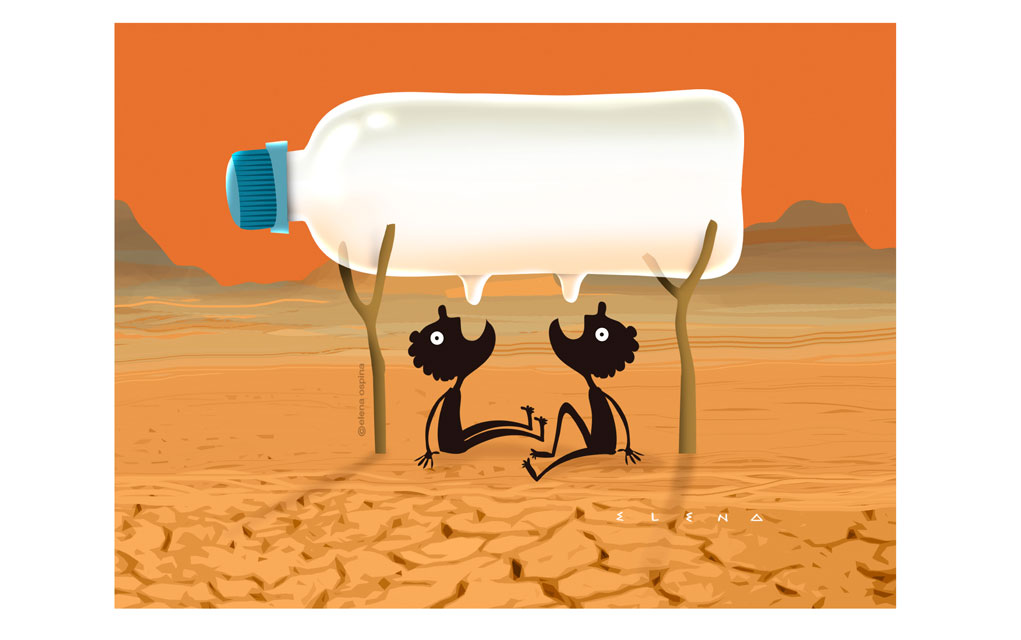

The work of documentation takes many forms, and the festival includes art exhibits, film screenings, workshops and learning labs, in addition to a variety of speakers from Bianca Jagger to Aridjis, renowned Cuban cartoonist Falco, Standing Rock Chief Dave Archambault and more.

As ALEF continues to grow, Vilar says it will provide a space for everyone, not just Latino environmentalists, to come together, build trust and move the conversation forward by “using arts and culture to ground our movement and tell our story.”

—Angela K. Evans

A conversation with Rudy Arredondo from the National Latino Farmers and Ranchers Trade Association

Despite losing a good deal of federal funding over the last several decades, there are still 95,000 Latino ranchers and farmers across the U.S. who comprise the membership of the National Latino Farmers and Ranchers Trade Association (NLFTRA).

Rudy Arredondo, who founded the association in 2005, says the NLFRTA was created because Latinos (and black, American Indian and female farmers and ranchers) were not getting the resources that their white, male counterparts were. That discrimination took, and continues to take, multiple forms, Arredondo says.

“Latinos, African Americans, women… the likelihood is that the [U.S. Department of Agriculture] will say, ‘You don’t qualify,’ without going through the [application] process,” Arredondo says of receiving federal funding. “Some of them are very direct and say, ‘You Mexicans don’t qualify, you’re a farm worker.’

“The other [form of discrimination] is more subtle… When you go into an office they’ll tell you, ‘Oh, we don’t have any money, ‘which may be the case but you are not given any instructions in terms of when there are going to be funds available for this particular program. So if you are not on the rolls, it’s unlikely you are ever going to find out when the money is going to come in.”

Part of the NLFRTA’s recent work was to influence the last iteration of the farm bill, the federal government’s main agriculture and food policy tool. Arredondo says the association was able to get language in the bill that required documentation anytime a rancher or farmer inquired about a service with the USDA or other office. Still, Arredondo says “folks’ habits change very, very gradually,” and minority farmers are still not guaranteed cooperation at the federal level.

Arredondo has a personal relationship to family farming. His family owned land in Texas, on which they farmed, before moving to Ohio to find year-round work in manufacturing. The family eventually amassed seven small farms, and Arredondo, seeing that many families like his had to make do on their own, sought broader impact, first joining the Chicano movement, then getting into policy work at the USDA under the Carter administration.

Arredondo says the policy work done by NLFRTA provides a valuable resource to minority farmers, who are often too busy to take off time to try to impact issues at the federal level. If not for NLFRTA, such influence would be left solely to Big Ag even though NLFRTA members produce 22 percent of the food that actually ends up on the plates of consumers. Arredondo says there is a major lack of representation outside the association for these workers.

Other federal policies are also impacting Latino farmers. Though the ending of DACA will be “chaotic” for NLFRTA members and their families, Arredondo says, that policy decision “was beyond the reach” of the association. He says the decision only placates people who did not adapt to changing times.

“It’s incredible that we’ve arrived at this place that we have a president who is as cruel and vindictive as this person is,” Arredondo says. “Totally disengaged in terms of real issues. … What’s happening in rural America is you have the white population… they just don’t have the necessary tools to be able to reinvent themselves in terms of what to do in the case where manufacturing and other things left both in the South and the Midwest.

“When they lost those [manufacturing] jobs, they were totally unequipped to be able to find ways in which to sustain themselves. … White privilege is addictive. So that’s what you have today: you have those folks that never thought beyond the immediate living standards, and they did not prepare themselves. What they see now is a lot of Latinos and immigrants who work very hard.”

The model that many Latino ranchers and farmers have undertaken calls for smaller farms with a built-in place to sell goods. Often the rancher or farmer owns that establishment, like a restaurant or a grocery store. Arredondo says the efficiency of this model doesn’t sit well with folks who operate on outdated models.

“The white population sees these folks and say, ‘They’re not entitled to this,’” he says.

Currently, the NLFRTA is focused on getting a younger generation of minority ranchers and farmers into farm ownership positions, while also encouraging moves to policy positions. In addition, Arredondo operates a farmers’ market in conjunction with the University of the District of Columbia’s College of Agriculture, which provides small farmers and ranchers the opportunity to sell their goods in an urban setting. The two groups are also working to provide scholarships to minority candidates, as Arredondo says traditional funding for college from 4-H and the USDA Farm Service Agency has mostly eluded Latinos and other minorities.

—Matt Cortina

Recreation first: Gabe Vasquez lets love for the outdoors guide its protection

Gabe Vasquez has a motto: “Recreation first.” What he means isn’t fun and games above all else; he means when it comes down to saving the environment, if recreation comes first, then the rest of the work will follow.

Vasquez is the New Mexico Wildlife Federation’s southern outreach coordinator, and also serves as a volunteer coordinator for the area’s Latino Outdoors chapter in his free time. He explains what he’s learned after years working as an environmental advocate trying to inspire others to care about the planet: “You have to love something before you want to take care of it.”

This is a motto he wants to bring with him to Americas Latino EcoFestival (ALEF). “I want to share what’s worked for me: Recreation leads to advocacy.”

Vasquez lives in Las Cruces, New Mexico, a city you might pass through if you were driving the 280-mile stretch from El Paso, Texas, to Gila National Forest, the first designated wilderness area in the country. “We have a majority, Hispanic population here,” he explains, “and we have a lot of issues with our environment.”

To get people hooked on protecting the environment, Vasquez helps them fall in love with outdoor spaces by showing them firsthand how powerful spending time outside can be. During one of his most recent projects — defending the Gila River from proposed diversions — he lead an initiative to take the diocese of the local Catholic church and a few priests out on a fishing trip. “We spend days on the river, camping and fishing … Many of the priests had never camped or fished before.”

According to Vasquez, that fishing trip led the Catholic Church to imbue the importance of protecting public lands into its Sunday mass. Eventually the church took an official position against the river’s diversion. “The Catholic Church has an important influence on the Hispanic community here. I’m Catholic,” he says. “Its endorsement of the environment meant a lot.”

This will be Vasquez’s first time at ALEF. “Anytime I can get together with people working on the same issue, I’m excited to learn from them and share what I’ve learned.”

During the festival, Vasquez’s primary mission is to continue collaborating on ways to get Latinos involved in environmental advocacy, especially those living near environmental hotspots. As his experiences — like going fishing with the priests — have taught him, involving people directly affected, or at least living nearby areas with environmental issues, can yield the greatest impact. “The [demographics of the] majority of people that work on environmental issues does not reflect the population that lives here. We want to get more Latino families involved. My goal is to get them out on the land and to enjoy outdoor recreation — inspire them to take care of our land and water.”

He believes the mission to protect the planet is so important because the environment plays a powerful role in humanity’s health. “Our land and the opportunities that our land gives us are transformational. As Americans, this system of public lands and waters that we created is a great source of health, exercise and therapy for many. As an opportunity to increase mental health, our land gives so much to us. It’s our duty to give back what the land gives us.”

He continues. “And that’s all of us, everyone. The EcoFestival brings together us all, from all over the world, even those who might feel like outsiders, especially if you’re Hispanic working in the outdoor industry. Hopefully this grows the people of color working to protect our sacred spaces.”

—Emma Murray

More Info: Americas Latino EcoFestival. Sept. 15-17, Denver Museum of Nature & Science, 2001 Colorado Blvd., Denver, americaslatinoecofestival.org

Schedule of Events

Thursday, September 14

6:30 p.m. GreenLatinos Welcome Reception #ALEF2017

7 p.m. USFS & AFC+A WOCC Partners Meet & Greet (Invitation Only)

Friday, September 15

9 a.m. Colorado River Summit: A Source to See Vision LIMITED

10 a.m. U-CAN Bioblitz United Cultures for Arts + Nature

12:15 p.m. Colorado River Summit Luncheon (By Invitation Only)

6:30 p.m. Ripples of Hope Fiesta & Awards: Pianist Daniela Liebman in Concert & Baragutanga in Dance & Special Guest BIANCA JAGGER LIMITED

Saturday, September 16

9 a.m. #GreenLatinos Learning Lab Summit in Five Parts: Priorities, Lessons, WaterIsLife, Protectors Ceremony, Raising Our Voices

9:10 a.m. Part One: GreenLatinos Core Priorities – Moving Critical Environmental and Conservation Issues Forward LIMITED

10 a.m. Part Two: Lessons from the Frontlines: How Communities Are Protecting our Water, Air, Public Lands, and Food LIMITED

11:30 a.m. Part Three: #WaterIsLife: Homage to Standing Rock and Our Shared Coalition (Special Guest: DAVE ARCHAMBAULT) LIMITED

12:15 p.m. Nuestro Hermano Award Ceremony: Dave Archambault, Standing Rock

12:30 p.m. Artivism Summit Late Luncheon (By Invitation Only)

1:20 p.m. Part Four: Guardians of Life Sculptures Ceremony of Alfonso Piloto Nieves Twelve Women Earth Protectors of the Americas

1:45 p.m. FALCO Artivism Exhibits Walk Tour

2:15 p.m. Part Five: Workshop: Raising Our Voices Through Strategic Storytelling and Artivism

6 p.m. Latina Environmental Giving Circle Tapas Forum

8 p.m. Bodies of Water in Search for Justice Film Festival: From the Colorado River to Lake Nicaragua to our Oceans (Special Guests: WADE DAVIS & BIANCA JAGGER ) LIMITED

Sunday, September 17

10:30 a.m. 2nd Colorado Re-Wild Book FairEnergiLAB BicycleGreen Fair

11:00 a.m. Promotores Verdes BioBliz Project Learning Tree StationsGraficoMovil: Climate of Hope on Wheels Printmaking Workshops

11:15 a.m. Mister G Latin Grammy Kids MusicHealing/Sanando Our Families Ourselves: Vinyasa Yoga Flow with Adriana Pulgar Therapeutic Healing Touch: Wellness for the Whole Family With Jorge Gonzalez

11:30 a.m. Maria the Monarch Book Presentation & Signing: Homero Aridjis

Noon. “Yo No Se” Song with Martin & GioEco-Artivist ChallengeGuided Tour with Artists

12:15 p.m. ALEF Animated Eco-Shorts Contest Official Selection

12:30 p.m. The Word May Sustain Us: Wade Davis and Homero Aridjis on Why and How Writing Matters to Environmental Justice

1:15 p.m. Nuestro Padrino Award Ceremony: Author Wade Davis & Congressman Jared Polis

1:30 p.m. Your Roots Are Your Wings: Upcycling Sculpture/Papier Mache Birds Workshop with PILOTO

1:40 p.m. Mariachi Sol de MI Tierra

1:50 p.m. ALEF Animated Eco Shorts Contest Official Selection

2:25 p.m. Mister G Latin Grammy Kids Music

2:45 p.m. Huellas Latino Leaders Book Launch

3 p.m. Tracing the Origins of Our Food Systems: A Hands On Permaculture Lab Awake: A Dream From Standing Rock Film Q&A with Director JOSH FOX

3:30 p.m. Mariachi Sol de Mi Tierra

3:45 p.m. Promotores Verdes Graduation Ceremony

4:15 p.m. Baracutanga Music Concert

4:45 p.m. Mariachi Parade

5 p.m. Planetarium Show Belisario: The Little Big Hero of The Cosmos