In the beginning, Tamara Williams Van Horn loved her time at the University of Colorado. She was recruited from Ohio to enter the sociology program; CU flew her out and introduced her to faculty members. A “we interview you, but you interview us” scenario in which the goal was to sell Williams Van Horn on a program and a school that had expressed interest in increasing diversity. The department never made any bones about its abundant whiteness, Williams Van Horn says, but the tour concluded with “an extra little supplementary piece just for me showing me the four black people that were on campus.”

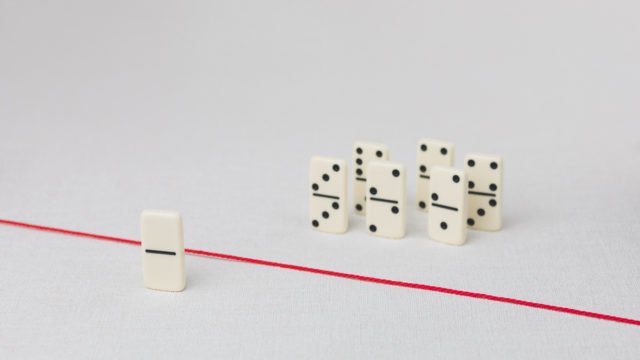

Since it was founded 60 years ago, the CU sociology department has graduated only five black doctoral students. Many more students of color, like Williams Van Horn, dropped out or transferred before completing their degree, citing racial discrimination within the department and across the university as a whole as the main reason. Those who claim to have experienced this discrimination say it took many forms such as reduced departmental support, increased teaching workloads, unwilling advisers and derogatory comments. And despite student surveys that appear to confirm these concerns, as well as others such as gender discrimination and sexual harassment, those within (and recently exiled from) the program say a lack of leadership within the department is the main reason the cracks within the system continue to widen.

The department’s alleged failures on discrimination may be a symptom of university-wide directives that include a push by its leaders to bring the university in line with their more conservative perspectives. In recent years, CU has pushed to bring in conservative speakers, advertised the school in conservative publications, and now hosts a conservative thought scholar. According to critics, the casualties of this ideological war on campus culture may be that legitimate claims of discrimination are being viewed as nothing more than a tactic of the “identity politics” of progressives.

Williams Van Horn worked in human resources in the private sector before rerouting her career toward a doctorate in sociology. At 33, her goal was to get a degree within four or five years, then return to help black communities in Ohio. CU promised she could accomplish those goals, Williams Van Horn says, and for the first couple years it was “a utopia.”

“I had a blissful experience,” she says of the first few years in the department. “I was the department cheerleader. I was doing professional seminars. I was going to different places on campus to represent the department. I was going to recruiting functions.”

And despite being the first person in her cohort to pass the tests that place students on their doctoral track, she was also teaching a lot. More than others in her cohort, she says. And, she was being switched between courses from semester to semester, meaning that she had to develop more curricula, read more books and generally spend less time on her doctoral work than her peers. In her seven years in the program, Williams Van Horn was asked to prepare eight different courses — well more than most tenured professors, she says.

Jo Painz, a graduate student who entered the year before Williams Van Horn, says for every hour of class, teachers are expected to spend four hours prepping. Painz, who also left the program recently due to what she perceives as a lack of support and organization from faculty, saw first-hand how that workload affected Williams Van Horn, and how different students and faculty treated her from her peers.

For instance, Williams Van Horn was reported to the CU’s Office of Discrimination and Harassment (ODH) (now under a different name) more than anyone else in her cohort for classroom issues.

“By the time I was done, we were all on a first-name basis,” Williams Van Horn says of her relationship with ODH.

Those complaints spanned everything from claims that Williams Van Horn “was angry at white people and I take it out on them” to one claim that she made a Christian student attend a “pro-choice rally.” (In actuality, Williams Van Horn says, every student was asked to attend a panel on reproductive health, and the complainant never mentioned an ethical concern with the issue, nor signed in to the event, nor told anyone she was there before she “approached the door and heard things that were against [her] religion” and left.)

Those kind of claims against Williams Van Horn routinely made it to the ODH. That was not the case for Painz and her other white colleagues.

“I don’t think we have anything distinctively different about our teaching styles,” Painz says. “I am 100 percent not a warm, caring and compassionate person and I had one complaint the entire time.”

Much has been written about the “snowflake” culture of college campuses, but the issue isn’t with the complaints themselves; it’s how the department, and university, treats the complaints made against black teachers versus white ones. Painz says Williams Van Horn received standing ovations when she gave guest lectures in her classes, but when a grading component was involved, there was more scrutiny placed on the person of color, than the white person. That’s a problem with a solution, Williams Van Horn says.

“If the department had stepped up, stepped in and said, ‘This is ours to handle,’ it never would’ve escalated to ODH,” she says.

Instead, she says, the concerns were not only passed on, but she was then given advice from within the department that differed from what she thinks white department members received.

“[Faculty members told me], ‘We know you. We know how good you are with students one-on-one. If you could just transfer that warmth to when you’re lecturing, then it would just be so much better for everyone, right?’

“That was the point when I snapped and said, ‘Can you please give me a scale of warm? Is it Oprah warm? Is it Mammy from Gone with the Wind warm? Or is it The Help warm? I really need to know on the black woman warm scale where you need me to be because I thought I was a scholar and a scientist.’”

Too, Williams Van Horn says when she started dating (and eventually marrying) a man, the “feminists” in the department told her she “was a much better person before I met him.”

So Williams Van Horn quickly soured on what had been her utopia, but she kept teaching and working toward completing her thesis and doctoral degree. That’s when, beginning around 2008, the department started to change, she and Painz say. Gone was the focus on getting students into either a research or teaching track. And in was a focus on just research, spreading thin those established students who did teach (like Williams Van Horn and Painz). Making matters worse, certain faculty members left, many of whom took year-long sabbaticals, leaving students without advisors at critical junctures. Williams Van Horn says her advisor gave notice of her sabbatical the day before she left on it.

Department heads came and went, bringing in varied focuses — some wanted an accelerated program, others wanted to maintain a longer track. Professors came and went through a revolving door.

That all made it hard for people like Williams Van Horn and Painz to stay on track. They each went through two advisors, and had trouble assembling panels to approve important program milestones. After a while, neither knew many of the professors, and so had difficulty building critical relationships.

But that departmental shape-shifting also revealed deep cracks of racism and gender discrimination, Williams Van Horn says. Faculty members started to hole up in their own research.

“Instead of using their tools, they just went into la la land, which was their own individual research,” Williams Van Horn says. “Like they forgot about everything else and it became, ‘My research is the most important thing.’ Teaching falls by the wayside. Running a department goes by the wayside.”

When concerns were expressed about discrimination, the department would listen, Williams Van Horn says, but nothing was ever done about it. Thus, grad students worked to create a climate survey that would better assess how those within the department felt about racial and gender issues and how the faculty was responding to it.

The 2016 survey found that only 4 percent of students felt the department was very successful with the recruitment, retention or support for students of color — about 53 percent said it had failed in that endeavor. Equally important, about 85 percent of grad students “expressed some level of concern about being retaliated against” for complaining against a faculty member.

Erin Campbell (not her real name), a grad student who helped develop the survey, says the fear of speaking out extends to students who have left the program, who are still concerned that having their name associated with complaints will prevent them from future opportunities.

Indeed, Boulder Weekly reached out to more than a dozen people who had either left the department or who were close to finishing the program, and many declined to comment out of a fear of retaliation or that their reputation would take a hit.

As an example of that retaliation, Painz says when she decided to switch advisors, she was given the silent treatment by her former advisor and the person who had originally recommended that advisor to Painz, which is a sort of death sentence in a culture that mandates connections.

The problem, according to at least six current and former grad students (most of whom asked that their identities not be made known out of fear of retaliation), is a lack of leadership and accountability in the department. Any talk of increasing diversity is just PC lip service, they say. The reality is that even when it’s not outright racism or sexism, which they allege is common, it’s an unwillingness to work with certain people. That creates a cycle where marginalized students are not given proper support, therefore they flail in their tracks, and eventually they are asked to leave, critics say.

“No one’s saying that this is just a witch hunt for students of color, but students of color are not treated in the way white students are,” Campbell says. “I think it’s important to think about faculty not only being uninterested but passing off students of color. For some reason, students of color have more advisors ‘breaking up with them,’ leaving them in a position where they don’t have support. So then therefore when they’re asked to leave [the department], there’s no one to fully support them.”

Both Williams Van Horn and Painz claim they had physical breakdowns that led to their exit. Painz left for eight months, losing 30 pounds, because of the uncertainty of her future in the department and the stress of trying to make it work. Williams Van Horn says she experienced blood clot-like symptoms before an important research presentation, and after she presented in spite of the medical issue, she went to the emergency room to receive treatment. She says the faculty treated her as if she chose to come down with those symptoms.

“That lead to an extreme anxiety episode where I could not answer email, go outside,” she says. “My husband had to handle all communications with me for three months. I turned my phone off, and I was like, ‘I’m done with the world for a minute.’ Just seven years of work, moving away from my family, a little bit of sacrifice, $200,000 in debt. Living in Boulder for seven years, when I was only supposed to be here for four.”

She says when she left, no one from the department called her. No one checked up on her. Not even her advisor, for whom Williams Van Horn babysat. The Office of the Registrar was the only one to reach out, and they just asked her to submit the grades for the courses she taught.

When Williams Van Horn attempted to return, she was given a tight deadline to get back on track. She met those deadlines, she says. Nonetheless, she says she was denied a chance to present her research, which would have given her the opportunity to write a dissertation. This after seven years and countless hours of courses taught for the department. Nonetheless, she planned to finish out the summer course she was scheduled to teach.

“About a week into it, I was like, ‘I am not coming back. I’m done,’” she says.

In addition to Williams Van Horn, several other grad students and faculty members have recently left the department. Hillary Potter, a former sociology professor, called herself “an outsider” in a letter to students and faculty in which she listed observations from her 11 years in the department. In the letter, Potter says it’s sad that sociologists don’t “recognize racial intolerance, … sexual harassment, … [and] classism when they see it.” She implies the department questions whether foreign-born professors with accents can “connect” with students, a claim Campbell, Williams Van Horn and others have corroborated.

Potter, who is now in the ethnic studies department, says the transgressions in the sociology department are still ongoing.

“I spoke out a lot and regularly begged the administration (including Chancellor [Phil] DiStefano, Provost Russ Moore, Vice Chancellor Bob Boswell, [Arts and Sciences] Dean Steven Leigh) — even after I was transferred to ethnic studies — to do something about the sociology department,” Potter says in an email. “With all that, not much, if anything, was done to correct the decades-long racial problems in that department.”

But not all people of color who have left the department did as a result of racism or discrimination. Citing many reasons including professional enhancement, funding and resource availability (including an African studies center) Sanyu Mojola expressed in a letter to colleagues that her move to the University of Michigan was mischaracterized by her peers as racially motivated. Though Mojola writes that she has experienced racism both in the classroom and in Boulder at large, it’s important to note “that there is a diversity of experiences” among women of color, and that reducing her decision to leave to her skin color is erroneous.

BW reached out to many other sociology faculty members for this story, asking for comments on the allegations of racial and gender discrimination outlined above. What we got was a response from CU spokesperson Ryan Huff, who says he had been notified by faculty member(s) of our inquiry and primarily cited one ongoing investigation regarding sexual harassment within the department. We assume this ongoing case is their reason for not responding.

“We take all allegations of harassment very seriously,” Huff writes. “We looked into the allegation made by a sociology department employee in April (reported via Colorado WINS, a union that has no official relationship with the university) and did not find evidence of harassment.

“We understand there are climate concerns among graduate students and we want to better understand those issues to create a more welcoming environment for all.”

Painz says she feels “horrible” for not reaching out to the students who she saw sort of float away from the department — and then she became one of them. Painz now works at a community college, which she says she prefers given the increased diversity in her classes. Williams Van Horn works in a craft shop. Her husband still works in the department. She says she largely gets pity from her former colleagues when she runs into them.

“Like cancer. It’s the cancer how you doing? I say, ‘Every day I don’t have to come here I’m fine,’” she says. “[But] that’s what the narrative is: If you’re gone, you did it, and you couldn’t hack it. It wasn’t until after I left that I realized I had normalized that. When other people leave, you just learn to keep your head down and not acknowledge it.”