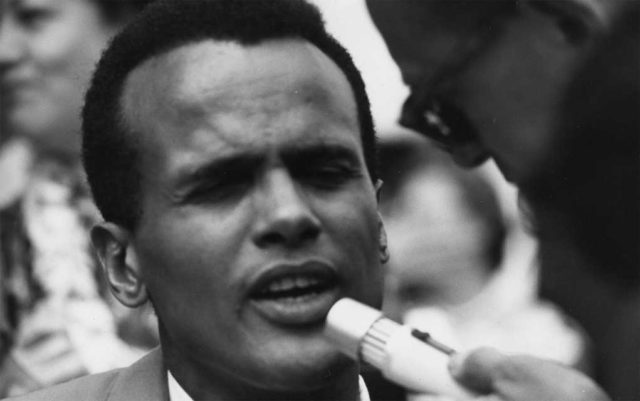

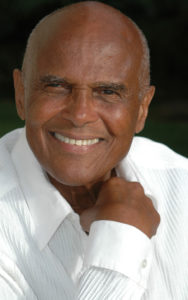

There’s a specific texture to his voice when he speaks, a raspy tone to his words. At age 90, he employs a certain cadence reflective of an earlier generation’s charm. A time when using the titles of Ms. and Mr. or inquiring about the weather didn’t signify a formality but was a way of establishing human connection, a way to move the conversation not only forward but deeper. After a brief discussion of Colorado’s sunshine, Mr. Harry Belafonte launches into his memories of James Baldwin and his thoughts on the new documentary I Am Not Your Negro. The singer, actor and activist will be in Fort Collins on Friday at a screening of the film on the closing night of the ACT Human Rights Film Festival at Colorado State University.

“I knew Mr. Baldwin pretty well,” Belafonte begins, reminding me the two spent quite a great deal of time together at the American writer’s home in the South of France.

“He left to go to France because the issues of race suffocated him,” he says. However, “I think the great upheaval in this country on the issues of civil rights struck a chord of great guilt in Mr. Baldwin himself. That he was in France while the rest of his clan was struggling with the issues of segregation and all of the things that the civil rights movement stood for.”

An outspoken champion of human rights for more than 60 years, Mr. Belafonte himself was intricately involved in the civil rights activism of 1960s America. He was a close friend and confidant of Martin Luther King Jr., bankrolling the King family for years with the fortune he made as a singer and actor. He spoke at the historic March on Washington in 1963 and joined Baldwin in his meetings discussing race relations in the U.S. with then-Attorney General Robert Kennedy.

“I watched [Mr. Baldwin] agonize over his conflict with America,” he says. “I was always aware of it, but [watching the film] I became very once again touched by the depth of his anguish and pain. It wasn’t just that he was upset with the issue of race, he was deeply pained by it.”

Scripted from Baldwin’s unfinished work Remember this House about Medgar Evers, Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcom X, Mr. Belafonte calls I Am Not Your Negro a “beautifully constructed” piece of cinema. But more importantly, he says, it addresses a deeper nuance in the discussion of race in America, a discussion still required today.

“It falls into a certain social hypocrisy,” he explains. “We speak to the glory of this nation, we speak to higher moral standards. We speak to all sorts of things that would suggest we are the practitioners of love on a wholesale basis. But the truth of the matter is … we’re building more prisons in America than we’re building universities, than we’re building schools. These are the things that constantly demonstrate that we’ve got to find a way to stop the hypocrisy and become more honest, understanding what we’re doing to one another and flip that coin.”

He says the great dream, the great hope of the civil rights movement, was that America could not only extol the ideals of democratic equality but truly embody them. It is a dream that extends to this day, the belief that “we can achieve a truly democratic state by the large configuration of mixed races, mixed cultures, America the melting pot of the universe,” he says. “We sense this aspect of our historic character, but we don’t seem to be comfortable with it.”

From the conquering of Native Americans when Europeans first arrived on the continent to the slave trade, 100 years of slavery, another century of segregation, and now the mass incarceration of a disproportionate number of African-Americans, true integration still alludes us, Mr. Belafonte says.

“There seems to be a redundancy in social behavior,” he says. “We just don’t seem to be able to yield, to take the higher moral view of race in this country. And I think it is eating away at the American soul.”

Not that there hasn’t been progress, he maintains. Slavery was abolished, the Civil Rights Act and other laws passed and have been upheld in the courts.

“But the process is excruciatingly slow,” he says.

“All that being said, there’s still this strain on our social integration,” he continues. “The great problem we have of the conflict with law enforcement, the shooting down of young black men, the insistence of having laws like stand your ground.”

It’s a law he says that directly points to the deep racial division in the U.S., despite what its advocates argue. Still engaged as a humanitarian and activist, Mr. Belafonte is unafraid to point out our shortcomings. And it’s always been that way.

As the civil rights movement waned, Mr. Belafonte went on to protest South Africa’s apartheid government, help raise awareness of the AIDS epidemic on the African continent and work as a UNICEF Goodwill Ambassador. More recently, he co-chaired the 2017 Women’s March on Washington and works with the ACLU to promote criminal justice reform.

“All the integration and harmony that takes place in the practice of arts, culture, theater, sports, it all seems to work,” he says. “But we have not been able to translate that into social conduct. …”

“Dr. King once said, the greatest display of the separation of races can be seen every Sunday because we all go to worship at our different places of choice but it’s never really with each other.”

Mr. Belafonte often evokes the memory of his friends now gone, peers in the civil rights struggle who have since passed away. Unprompted, these references aren’t for show. It’s clear he holds their words close, small reminders of what has yet to be achieved.

“As Eleanor Roosevelt, who was a very close friend of mine said, we’re putting a terrible burden on the educational system, trying to hold the schools of America responsible for practicing the higher art of integration, when in fact the burden shouldn’t be on schools, it should be on communities,” he says. “As long as we stay a separate society, our institutions behave in a separatist way.”

There is a point in the conversation where a hint of disappointment creeps in, an acknowledgement of the fact that despite all Mr. Belafonte and his peers accomplished, there still seems so much left to do.

“[I] wish it would have happened from the life I have lived in the past, but it seems to be an eternal journey.” He pauses. “I’ve spent so much of my life being touched by issues that have to do with race and I would like to overcome that. I would like to get that out of my vocabulary, get that off the canvas. I’d like my palette to be of different shades of human expression.”

And yet the issue of race persists in the U.S., making films like I Am Not Your Negro more pertinent than ever.

“We still have to push aside these obstructions,” he says. “The sooner we do that, the more joyous we will find ourselves as a people. I really believe the rewards are far more delightful than the pain and the anguish we are experiencing trying to understand each other.”

On the Bill: I Am Not Your Negro followed by a Q&A with Harry Belafonte. Friday, April 21, 7:30 p.m. Lory Student Center Theatre, 1101 Center Ave. Mall, Fort Collins, 970-491-6444.