On Dec. 5, 1933, the 21st Amendment to the United States Constitution was ratified and alcohol prohibition in America came to an end.

Although 83 years ago, the rise and fall of national alcohol prohibition in the U.S. offers help in understanding drug prohibition and regulation, specifically with regard to marijuana. Now, as both the United States and international political systems challenge longstanding anti-drug laws, they face dilemmas eerily similar to those of nearly a century ago.

Governments struggle to rationalize the rising human and economic costs of the enforcement of harsh drug policies, to negotiate the dance between moral and scientific approaches to drug laws and to confront the unstoppable use of cannabis and other drugs throughout the world.

In many ways, we are in uncharted waters, facing a set of circumstances unique to our time and place, but, armed with the wisdom of hindsight, there is also a lot to be learned from prohibitions come and gone.

The 18th Amendment, the one that instituted prohibition in the first place, was passed in 1917 just after World War I, not long after the first anti-drug laws were established. The amendment supplanted an earlier wartime prohibition act meant to aid the war effort by saving grain that might otherwise be used for beer and whiskey.

But the social movement for the prohibition of alcohol began much earlier, in the early 19th century, with the formation of temperance societies concerned about the adverse moral and social effects of drinking.

By the late 19th century, these groups had become a powerful political force, successfully campaigning to outlaw the manufacture and sale of alcohol in several states.

The nation officially outlawed liquor on Jan. 17, 1920. But, while prohibition may have outlawed alcohol, it certainly didn’t get rid of it. The black market for alcohol was an enticing opportunity for smalltime bootleggers and masterminding entrepreneurs alike, and alcohol poured into thriving underground markets.

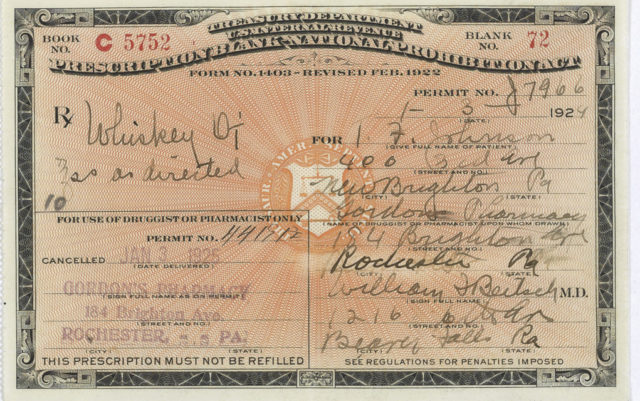

These illegal operations supported a bustling scene of illegal speakeasies. There were even legal workarounds as doctors filled prescriptions for liquor as a palliative to certain diagnoses, like tuberculosis, that could be picked up in pharmacies. And so it was the money made from selling illegal liquor that filled the pockets of some of the most notorious gangsters in U.S. history, like Al Capone and Legs Diamond, as well as pharmaceutical companies.

As established by the Volstead Act, passed in 1919, it was the government’s responsibility to combat these black markets. But cracking down cost money — and lots of it — somewhere in the tens of billions of dollars.

Failing fully to enforce sobriety, popular support for prohibition spiraled into rapid decline in the 1930s. The Great Depression had a way of making enforcement expenditures appear excessive (especially when compared to the tax revenue to be gained from a legal alcohol market) and boosted people’s demand for drink.

Challenges to temperance laws were being introduced at both state and federal levels and, in 1932, the Democratic Party endorsed total repeal at its convention. A year later, with Roosevelt in the presidency and a Democrat-controlled House and Senate, federal prohibition was repealed.

The associated enforcement costs stopped immediately, but those expenditures didn’t just disappear. Soon enough the criminal groups working under prohibition moved onto other illegal activities like prostitution and drug markets.

And just as prohibition wound down, anti-drug sentiments heated up, providing a convenient place for anti-alcohol interests to relocate. In 1930, Henry Anslinger was appointed to head the newly created Federal Bureau of Narcotics and for the next seven years built a set of drug prohibition policies, controlled by the executive branch and bound by international treaty.

Without a lot of scientific evidence to bolster his effort, Anslinger led a heated media campaign against marijuana that adopted many of the maternalistic and moral strategies used by the temperance movement. Not only were his tactics successful with voters, but it led to the institution of government-imposed barriers to research on all illicit drugs.

It is this set of laws from the end of alcohol prohibition that the nation and world are challenging in state-by-state legalizations today. The motivations and arguments for the end of drug prohibition are nothing new: The costs outweigh the benefits, science on these substances is being harmfully repressed and the use of these substances persists regardless of prohibition.

Marijuana’s legal future is uncertain, that we know, but for the past eight years legalization movements have been met by a federal government that has been, more or less, accommodating.

But as one administration turns to another, it is likely that the political and scientific momentum behind legalization will be swept into a moral movement against it. As nominee for Attorney General Jeff Sessions said in April: “Good people don’t smoke marijuana.”