For journalist Adam Schrager, the act of playing sports is a pretty decent metaphor for life.

“Sports, at best, teaches wonderful lessons, from teamwork to hard work, goal setting. Everything that we do in life, you can see examples in sports of how you can get better in life,” Schrager says. “Yet ethics is essential also in how we perceive ourselves, and does the vision of our self marry with the reality of ourselves? I don’t know. I think sometimes it does, yet in the high stakes professional sports world it doesn’t.”

Schrager will sit down with three other panelists and discuss business and ethics in sports on Tuesday, April 5 at the Conference on World Affairs. Central to Schrager’s take on the topic are two forms of ethics: aspirational and situational.

Aspirational ethics are the highest moral standard to which someone can aim — of course these ethics are going to vary depending on a person’s culture, values and morals, but ultimately, these are principles based on an absolute moral standard.

While situational ethics aren’t the exact opposite of aspirational ethics, they encompass a looser set of rules. Here, someone takes into account the particular context of a situation and acts accordingly, and the choice may not come from a purely moral place.

“Frankly, when it comes to business in sports, situational ethics rule the day, where aspirational ethics are just something you write about, or when you win championships you get to talk about,” Schrager says.

There are two stories Schrager plans to bring to the panel table to exemplify these two ethical frameworks. One of those stories involves the University of Colorado Boulder’s 1990 football team — the team that won the national championship.

To make a long story short, the Buffs scored a winning touchdown as the clock ran out, and they did it on a fifth down — an illegal play that cast doubt on the team’s claim to the Division 1-A national championship that year (which they shared with Georgia Tech).

The scandal didn’t go without notice — referee J.C. Louderback and his crew realized they had failed to flip the marker to note the third down, resulting in the extra play. The refs conferred for nearly 20 minutes to decide how to proceed, and during the delay, radio and television announcers began to note the extra play. Ultimately, Colorado was awarded the touchdown and given the chance at the extra point.

Schrager worked for 9News in Denver at the time, and spoke with Louderback after the controversy.

“This one failure, one mistake ended up basically costing him his career,” Schrager says. “It fascinated me … this idea, from an ethical standpoint, what role you have in acknowledging when you know a mistake happened. Is it simply that’s how the game is played? Could the University of Colorado come out and forfeit that game? What are the ethics of that? What’s the business impact of something along those lines?”

In 2015, Lindsey Koehler wrote about the so-called fifth-down scandal for 5280, stating that it cost CU approximately $20 million, including revenue lost from a decrease in out-of-state enrollment.

This, Schrager says, is an example of situational ethics.

“Bill McCartney proclaimed to be as soulful a man as there was,” Schrager says of the conservative Christian head coach of the Buffs at the time. “Yet he was very content to not apologize.”

Schrager points to an older story as an example where aspirational and situational ethics met.

In 1957 the University of Wisconsin was set to play a two-game series with Louisiana State University — one game in Madison, one game in Baton Rouge. But just the year before, in 1956, Louisiana passed a law prohibiting integrated sports contests, barring black athletes from competing with or against white athletes.

At the time, Wisconsin had some of the first African American football players in the Big Ten Conference: starting quarterback Sidney Williams, halfback Denny Lewis and wide receiver Earl Hill.

Louisiana’s law had perhaps as much to do with bigotry as it did with winning football games — LSU had lost the Sugar Bowl in 1956 to the University of Pittsburgh, where African American Bobby Grier was a running back.

“The next legislative session, Louisiana state lawmakers overwhelming passed a measure to ‘outlaw social events and athletic contests including both Negroes and whites,’” Schrager wrote for WISC-TV in Wisconsin in August 2014.

Schrager says “in literally six hours of this law being passed in Louisiana,” the University of Wisconsin Athletic Director Ivan Williamson canceled the contract for the two games.

“Both of these teams were great,” Schrager says. “LSU wins the national title and Wisconsin is number 4 with one loss. The question to me is, who in today’s day and age would give up a chance for national stature like that on principle? On ethics?”

Schrager says he isn’t sure anyone would.

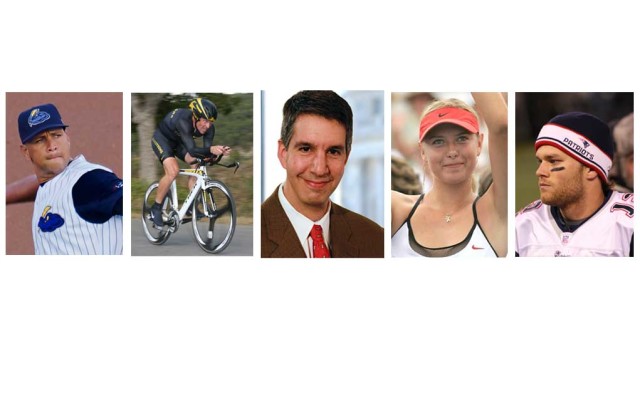

Football certainly isn’t the only sport where ethics seem to fly out the window in the face of winning. Schrager points to Maria Sharapova’s recent performance enhancing drug scandal. Then there’s Lance Armstrong, the New England Patriot’s “Deflategate” controversy, and accusations claiming the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill created bogus courses to help keep basketball players eligible. On an international scale, FIFA has been embroiled in what has been called a corruption crisis, with dozens of officials accused of being involved in criminal schemes.

For Schrager, it all comes down to being a good citizen, a lesson he’s trying to teach his young children as they make their first forays into participatory sports.

“I think being a good citizen means not taking what you don’t deserve at the expense of somebody else,” he says, then laughs. “That’s extortion in the criminal world, but in sports somehow that’s OK. Why is that OK? I don’t understand.”

Schrager will be joined on the panel by professional referee Ismail Elfath, economist Bill Martin, and journalist Joe Sexton, a senior editor at ProPublica.