It is eerie in Porter Ranch. It feels like an uber-rich Mayberry, if the Mayberry gas utility started leaking massive quantities of methane and forced everyone to evacuate. In the hills above gated communities — including Porter Ranch, which is on par with Bel-Air for Los Angeles County income supremacy — there are trails and one-lane roads that swoop and cavort the mounts covered in oil and gas sites, many of them decades old.

Down below in the streets of Porter Ranch, people are trying to return their lives to normal. You see them on mountain bikes and running trails, but it’s eerie still. More than 4,000 homeowners have yet to return. And just knowing that their absence is due to a massive natural gas leak makes you wonder if the cool steady breeze is carrying something just dying to give you a nosebleed or lung troubles.

If you squint, Porter Ranch looks a lot like parts of Colorado. In fact, for now, part of Porter Ranch is Colorado. A good portion of the contamination that has thrown this community onto the front pages of newspapers all around the world was pulled out of the ground in Colorado, transported via pipeline or rail to Southern California, stored in the Aliso Canyon storage facility in Porter Ranch where it then escaped into the atmosphere from an old well, saturating the air in the neighborhood and comprising the worst methane leak in U.S. history.

Yes, Colorado’s role in the Porter Ranch methane leak is integral. The methane from our natural gas that leaked in California is what forced the evacuation and relocation of thousands of families. What it shows is that no matter how strict the regulations Colorado puts on its oil and gas activities, the safety of the hydrocarbons we pull from our ground is often determined by other states and federal agencies. If Porter Ranch is to be seen as an example, the system is fraught with poor and inconsistent oversight policies. The infrastructure in place to transport and store oil and gas is weak at best — a recent Harvard study found the U.S. is the worst emitter of methane in the world. And by extension, Colorado as a major natural gas producer and distributor is one of the largest culprits when it comes to allowing methane to escape into the atmosphere. Research has found that the gas fields of the Four Corners area leak as much as 10 percent of their entire production every day. And as Porter Ranch made perfectly clear, large quantities of Colorado’s natural gas are escaping after the gas leaves the state.

Even when well and storage sites are abandoned across the country, new research indicates these old wells still leak massive quantities of methane and other harmful chemicals. And this major source of greenhouse gasses is mostly unregulated and unseen.

The Porter Ranch incident figures to go down as a watershed moment for regulating oil and gas storage facilities, and methane leaks. Over 112 days, about 97,000 tons of methane was released into the atmosphere alongside other contaminants from natural gas like methanethiol, benzene and ethane. The amount of methane released was historic: it comprised about 24 percent of the total amount of methane typically released in the Los Angeles region in an entire year. Releasing 1.6 million pounds of methane per day during the leak was the equivalent methane output of six coal plants, 2.2 million cows or 4.5 million cars on the road, according to data from multiple sources.

The Porter Ranch incident figures to go down as a watershed moment for regulating oil and gas storage facilities, and methane leaks. Over 112 days, about 97,000 tons of methane was released into the atmosphere alongside other contaminants from natural gas like methanethiol, benzene and ethane. The amount of methane released was historic: it comprised about 24 percent of the total amount of methane typically released in the Los Angeles region in an entire year. Releasing 1.6 million pounds of methane per day during the leak was the equivalent methane output of six coal plants, 2.2 million cows or 4.5 million cars on the road, according to data from multiple sources.

The leak at the Aliso Canyon underground storage facility was discovered after residents of Porter Ranch began to describe noxious fumes in late October 2015. The facility is the second largest natural gas storage facility in the country, and with 115 well sites, it extracts oil and gas from the underlying formations, as well as stores oil and gas shipped in primarily from sources in the Rocky Mountains and Texas.

SoCal Gas, a subsidiary of Sempra Energy, runs the facility and first told residents there was no major gas leak, according to the Porter Ranch Neighborhood Council. As the fumes continued and residents started to complain of physical issues like headaches and nausea, all symptoms of methane exposure, the state sent Steve Conley, an atmospheric scientist at the University of California Davis, to fly overhead and measure emissions from the site. Conley found massive quantities of methane escaping the facility, and SoCal Gas soon found a leak in a seven-inch-thick metal pipe about 500 feet below the ground that was used to move gas in and out of a well. Conley told the Sacramento Bee that he wasn’t surprised by the leak, as the well was over 60 years old, common for many storage sites in the U.S.

Local officials took 180 noxious odor complaints from residents in the first few weeks of the leak, and schools were forced to temporarily close down. Of the two dozen or so people Boulder Weekly talked to in Porter Ranch on a recent visit to the area — on sidewalks, running trails and shopping plazas — almost every person knew someone who had been relocated by the gas company, and who had experienced physical issues from headaches to lung problems.

By Feb. 18, SoCal Gas had put 1,968 households in long-term housing through apartment or rental homes (the company says it will pay to keep these people in their replacement homes through the end of March); and 1,309 households were put into hotels or with friends and family. About 4,800 households were put up in hotels temporarily, though now a majority of those people have since returned to hotels after a court ruled to extend the relocation period by three weeks as regulators test homes for methane quantities. The Los Angeles County Department of Public Health, along with other agencies, will test 100-200 homes to see if methane levels have diminished to safe levels before authorizing the return of residents.

The leak was capped on Feb. 18, but fixing it was a bit of a quagmire. The company tried numerous times to plug the leak by shooting materials down the old well; a move that ultimately failed because of the massive pressure emanating out of the well. Eventually, the company drilled a relief well about 8,000 feet into the ground, and sealed the well permanently. That process took several months.

Now, residents wait to hear the results of the regulators’ testing of methane levels in homes. Some residents, like those in the Save Porter Ranch advocacy group, are calling for an end to all oil and gas operations at the facility. The locals BW spoke with are mostly unconcerned about lasting air contamination, as the high winds and consistency of methane has likely blown hazardous amounts of the contaminant away and into the atmosphere; but many are concerned about contaminants lingering in homes.

Now, residents wait to hear the results of the regulators’ testing of methane levels in homes. Some residents, like those in the Save Porter Ranch advocacy group, are calling for an end to all oil and gas operations at the facility. The locals BW spoke with are mostly unconcerned about lasting air contamination, as the high winds and consistency of methane has likely blown hazardous amounts of the contaminant away and into the atmosphere; but many are concerned about contaminants lingering in homes.

SoCal Gas says the area is now completely safe and that “air quality levels in and around Porter Ranch are consistent with levels before the leak occurred.” The company cites independent readings from regulatory agencies.

But not everything is cut and dried about the lasting effects on public health caused by the Aliso Canyon leak.

The main concern for homeowners is that methane, benzene or other contaminants will build up in homes, causing ingestion issues as well as increasing the risk for explosions. Methane, from any number of sources, from an individual pipe leak in a home, to a release of sewer gasses, to infiltration from an outside source, as would be the case in Porter Ranch, can easily get trapped in homes, but SoCal Gas disputes that methane can latch onto clothes, carpets or other household effects.

“Unlike carbon dioxide, which can be captured both physically and chemically in a variety of solvents and porous solids, methane is non-polar and interacts weakly with most materials,” the company wrote in a statement to BW. The company cited a Scientific American article that called methane a “shy molecule, one that doesn’t interact much with its surroundings,” but that same article also confirmed that methane at high concentrations can make it easier for materials to absorb the gas.

According to the California EPA, the highest level of methane concentration recorded during the leak was 230 parts per million (ppm). Normal methane levels are about 2 ppm.

In the atmosphere, methane is 25-times more potent as a greenhouse gas than carbon dioxide over the course of 100 years and 72 times more potent over a 20-year span. Though methane lives in the atmosphere for a shorter period than carbon dioxide, it is much more efficient at trapping radiation that can warm the Earth, according to the EPA. Natural gas makes up the largest share of U.S. methane emissions, comprising about 30 percent of the total release of methane. And to be sure, residents in Porter Ranch who spoke with BW were far more concerned about the lasting environmental toll; some were even embarrassed for their region and the damage that the Aliso Canyon facility leak has caused.

Methane is also a contributor to smog and ground-level ozone, which inhibits air quality, can be very dangerous to people with respiratory problems such as asthma and contributes to global warming. That’s bad news in light of the Harvard study that recently found between 30 and 60 percent of global methane emissions could be coming from the U.S. This massive number is tied directly to a 30 percent increase in methane emissions in the U.S. since 2002 alone. Researchers have voiced their belief that this increase is related to the increased fracking of oil and gas shale in the U.S., much of which has occurred in Colorado.

In addition to methane, there were two other contaminants released in major quantities in Porter Ranch: methanethiol and benzene.

Mercaptans (as methanethiol is commonly called) are foul-smelling chemicals that are added to natural gas in order to make it easier to detect leaks. It’s what makes urine smell after a person eats asparagus, and it also is responsible for the smell of flatulence and bad breath. In fact, smelling it is how Porter Ranch residents first detected the leak at the Aliso Canyon facility. Mercaptans typically “do not cause long-term health effects,” according to Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment (OEHHA), particularly at the level experienced in Porter Ranch. That said, OEHHA admits that mercaptans can create nausea and headaches in people who smell it.

But mercaptans aren’t totally harmless. Four employees of a DuPont facility in Houston were killed in 2014 after exposure to high concentrations of mercaptans.

Benzene poses a greater and more immediate threat than mercaptans or methane. Benzene is a known carcinogen, and it was abundant at times in Porter Ranch during the gas leak. Benzene levels are still being registered by monitoring agencies. The EPA says there is no safe level of benzene.

Benzene is a naturally occurring part of crude oil and natural gas. People are commonly exposed to it via car exhaust, industrial emissions and from glue, paints and furniture. OEHHA says benzene levels during the leak were the biggest concern for regulators, as the concentration of the contaminant in the air was the closest to reaching what’s called a Reference Exposure Level (REL), or basically a standard of concern.

Early in the leak, in Nov. 2015, benzene levels were hovering right around the chronic REL of 1 part per billion (ppb). Since December, the benzene levels in the air around Porter Ranch have all been below 1 ppb, but not by much. January featured a steady level of benzene in the air, and a reading as recent as the morning of March 1 found levels above 1 ppb. The group Physicians for Social Responsibility say that “prolonged exposure [to benzene] may result in blood disorders like leukemia, reproductive and developmental disorders, and other cancers.”

So it’s worth noting again that when regulators go into Porter Ranch homes this month to test the air quality, they will only be testing for methane — not benzene, ethane, mercaptans or propane, which has also steadily shown up in air quality readings. SoCal Gas, for their part, has offered residents an air purification program to deal with odors by implanting a carbon filter that can remove odorant compounds in natural gas from homes.

What happened in Porter Ranch could easily happen elsewhere, and is happening on a smaller scale nationwide every day.

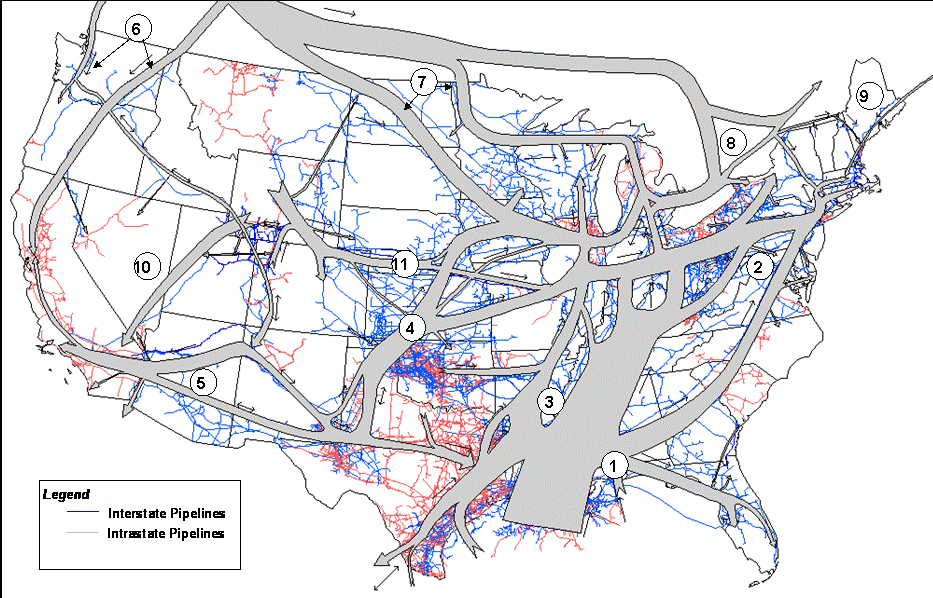

And though it was partly Colorado gas that sent residents of Porter Ranch running for their lives, it’s worth noting the Colorado Oil and Gas Conservation Commission that regulates the state’s oil and gas industry is powerless to prevent massive leaks such as the one at Porter Ranch. Nearly every home in the nation gets its gas from a series of pipelines that ultimately wind their way thousands of miles to a source at the wellhead. With every state regulating just a tiny fraction of the system, there is no entity responsible for natural gas from ground to home.

Natural gas is shipped from Colorado via two main sources: pipelines and trains.

Colorado hooks into the national pipeline system in almost all directions. East of the Rockies, producers can tap into pipelines that send natural gas to Wyoming, Kansas, Oklahoma or Texas, where it then taps into larger pipeline systems that send Colorado gas to California and the Midwest.

Gas leaving Colorado for storage below Porter Ranch can take a series of in-state pipelines from both the Front Range and the Western Slope. Eventually that gas taps into the Kern River pipeline, which feeds into Aliso Canyon. Just as another cautionary tale: The Kern River pipeline ruptured in 2012, releasing 585 million cubic feet of natural gas into the air. Much of that leak was also likely Colorado-produced natural gas. That’s about 4.5 billion gallons, which is difficult to conceptualize.

Think of it this way: it’s the equivalent of filling 4,500 football-field-sized swimming pools that are 10-feet deep. Just one pipeline in Colorado, the TransColorado pipeline system, can move about that much — 590 million cubic feet — natural gas through Colorado every day. And that’s not even the biggest pipeline system in the state.

So you probably think that regulation of these pipelines is pretty strict. Not so.

The federal government has only 100 full-time inspectors it employs from hubs nationwide. With so few feet on the ground, the federal government has no choice but to leave the day-to-day regulation of pipelines and other facilities to the states. By the numbers, about 13 percent of the nation’s total pipelines are regulated by the federal government. Colorado is one of the worst states for pipeline regulation, with only one regulator per every 7,000- to 8,000-miles of natural gas distribution mains. The responsibility of inspecting pipelines in Colorado falls to the Public Utilities Commission.

In total, there are only about 500 federal and state inspectors for the 1.3 million miles of gas pipelines, according to a Pittsburgh Tribune-Review investigation. This shortage of regulators has no doubt contributed to the rapidly increasing release of methane in the U.S. According to the Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration, 12.8 billion cubic feet of methane has been released from pipelines across the country in more than 700 incidents since 2010; events that killed 70 people, injured 300 and cost close to $1 billion in property damage. The damages attributable to global warming caused by such leaks is incalculable.

When crude or liquefied natural gas is transported by rail, the immediate perils are even greater. Though crude oil by rail transport went down in 2015 from 2014 levels, the last several years still represent elevated rail traffic of the volatile material. Shipments of crude oil by rail peaked at 15,000 carloads per week in 2015, which is still relatively high.

The regulation of crude oil transport by rail has come under major scrutiny in recent years. Inspection and regulation of oil trains is mostly done by the federal government, though states are now beginning to enact stricter laws. Currently, railroads are only required to notify local emergency personnel if a train carrying 1 million gallons or more of hazardous material comes through in its jurisdiction.

But the most dangerous part about transporting crude oil by rail is the cars in which they are transported: the DOT-111s. They are outdated and not suited for the type of crude typically shipped on rails today. Last year, the federal government called for an immediate phase-out of DOT-111s, but only for the oldest varieties, and so many still-dangerous, but newer, DOT-111s will stay on the rails until 2030.

But transportation is just one side of the coin regarding the safety of Colorado oil and gas in other parts of the country. As seen in Porter Ranch, there exist major problems with the enforcement of safety standards at storage facilities, as well as at abandoned wells.

At any given point, there is about 3.3 trillion cubic feet in underground storage in the U.S. For reference, it would take all 1.5 million wells in the U.S. to produce at full capacity for about a week to reach that storage number. Most storage facilities, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration (a government agency), are built in depleted natural gas or oil fields, as was the case at the Aliso Canyon facility in Porter Ranch. Other storage facilities, mainly in the Midwest, are built out of converted natural aquifers.

These storage facilities are owned privately, usually by independent storage facility owners or pipeline companies. About 120 companies own the 400-plus storage facilities in the U.S. Any storage facility that works between states is subject to federal oversight, and intrastate facilities are regulated by the state in which they operate. These storage facilities are as prone to leaking methane and other contaminants as an active well site, pipeline or abandoned well. By virtue of being built in old drilling sites, the 400-plus storage facilities are as old or older than the 60-year-old pipe that gave way at the Aliso Canyon site.

The state regulation of storage facilities varies — some states require every storage facility to be checked once a year, while others require more or less often. Some states have one or two regulators dedicated to storage inspection, others have none. And states have different requirements for what the inspectors are looking for — some states require only checks for visible or odorous contaminants.

That’s little comfort considering we are sitting on top of 3.3 trillion cubic feet of natural gas somewhat contained in man-made facilities or imperfect natural underground structures that are aging and growing weaker every day. The nonprofit group Earthworks posted an interactive map on their website that shows methane emissions from well sites, pipelines, storage facilities and more by using an infrared camera that detects methane. Do yourself a favor and visit the page, zoom in on Weld County and then start worrying about which way the wind blows.

The problem with storage facilities, it seems, is one of infrastructure; the problem with abandoned wells is one of carelessness.

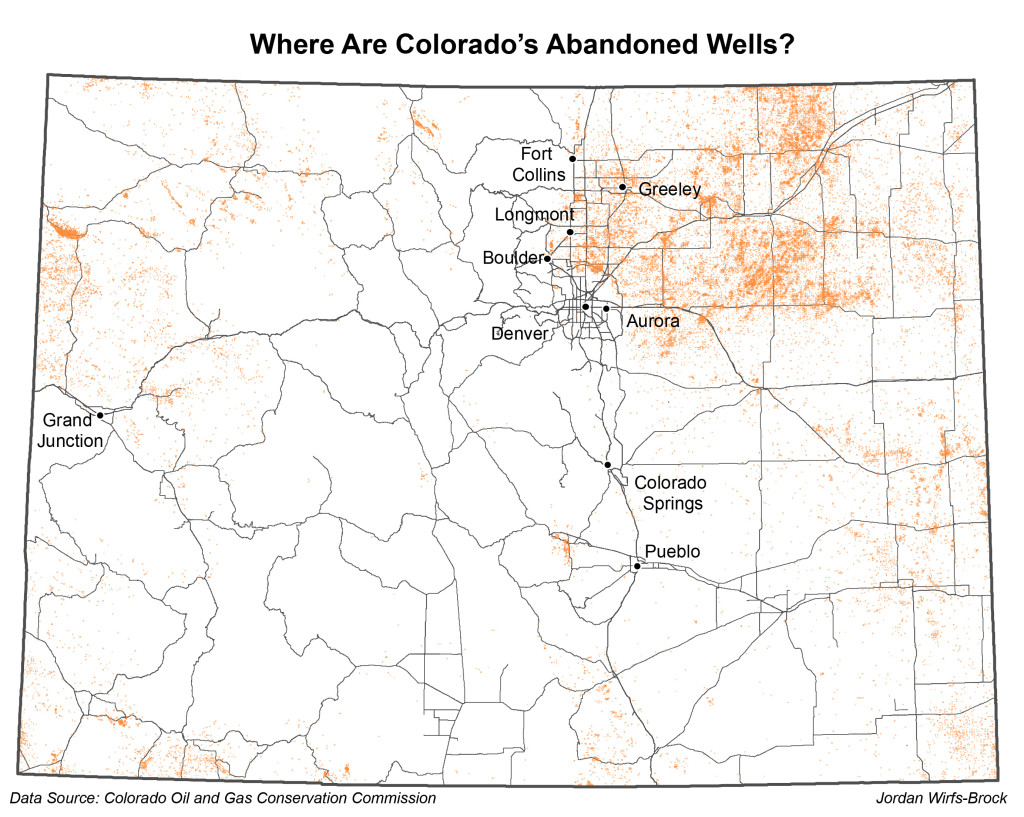

There are about 2.5 million abandoned oil and gas wells in the U.S., with about 20-30 million globally. There are about 35,000 abandoned wells in Colorado alone. Many of these abandoned wells were never plugged while others were plugged and capped with cement. As the cement cracks and otherwise fails, many of these wells start leaking methane into the atmosphere. And sadly, abandoned wells are not regulated by ongoing inspections.

So because they are unregulated, figures about the potency of their emissions are hazy or nonexistent in the U.S. However, a Canadian entity, the Alberta Energy Regulator, aggregated information provided by the province of Alberta, a major oil producing region, and found that about 7.7 percent of abandoned wells in the region are leaking. It seems fair to make the leap that in a country where abandoned wells aren’t even regulated, 7.7 percent is a comparable, or even low, range for leaking abandoned wells in the U.S.

What’s worse, in theory, is that because these wells are capped deep below the surface, it often means that buildings, including homes and schools, can be built right over the top of abandoned wells that might be leaking into water wells, drifting into air supplies or creating a store of powerful methane right beneath the surface. We just don’t know the depth of this issue: it’s not regulated.

There is precedent for abandoned well explosions, too. Three house builders in Trinidad, Colorado, were injured in an explosion in 2007, when a well that had been abandoned in 1984 and plugged by Halliburton leaked methane into the house. Methane continued to leak until the well was re-plugged.

And this doesn’t even speak to the thousands of off-shore wells, like the 3,500 abandoned wells that had openly been leaking into the Gulf of Mexico and hadn’t been discovered or regulated until the disastrous BP Deepwater Horizon spill.

For reference, the City of Longmont hired a firm to research and plug 17 abandoned wells, many of which had “perforations,” in 2013.

Given all this information regarding the national inability to keep methane in the ground, it’s no wonder that the residents of Porter Ranch are calling on SoCal Gas to end operations at the Aliso Canyon facility. However, the California Department of Conservation ruled recently that rather than shut it down, it will test the integrity of all well sites at the Aliso Canyon facility, pumping in pressure at 115 percent the standard rate to find leaks in the system. It’s a good step, but then again, California is one of the tougher states on emissions and oil and gas operations.

And so if the worst methane leak in U.S. history can occur there, in California, where there is some semblance of regulation, what and where will the next leak be in the oil and gas infrastructure of the U.S.? And given Colorado’s likely outsized role in that next leak, what responsibilities does this state have in ensuring the safety of its oil and gas once it leaves our borders?

The likely answer — so long as Colorado’s elected Democratic and Republican leaders remain mysteriously vested in the growth of the oil and gas industry — is none.

Correction: An earlier version of this article erroneously reported that methane comprised 20 percent of the atmosphere in Porter Ranch at the height of the Aliso Canyon facility leak. The correct concentration was 230 ppm.