Walk into the Art of the State exhibit and you will immediately step into the diverse Colorado art scene. Far from the galleries of New York City or Los Angeles, Colorado boasts its own rich and varied art scene, and it features more than just your typical cookie-cutter painting of Colorado’s landscape.

Art of the State is now at the Arvada Center through March 27. This is the second time the center has presented this show, and the hope is to continue to feature a variety of local artists in the future. Art of the State displays both contemporary and traditional art forms in a plethora of media. And the exhibit shows just how diverse our state can be.

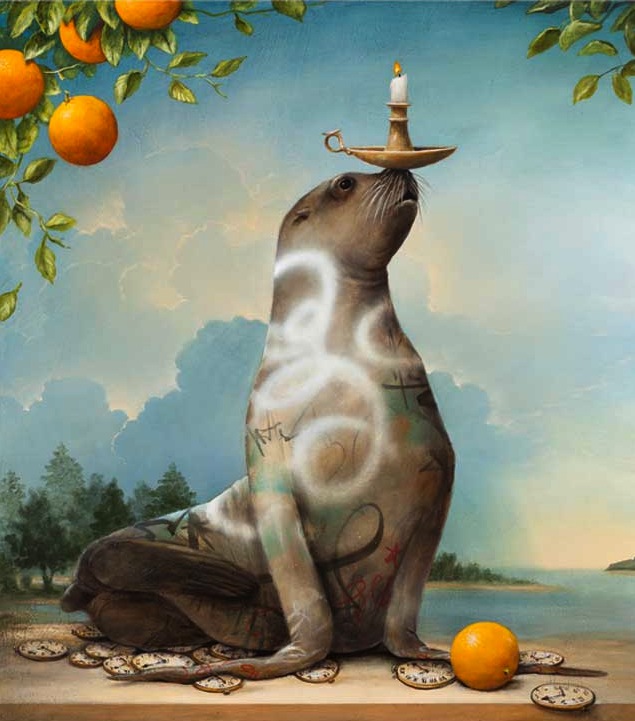

Kevin Sloan, the winner of the best-in-show award, uses more traditional forms. His winning piece is of an elegantly posed seal balancing a candle on its nose, called “St. Fortitude.” Amidst the picturesque landscape of a lake surrounded by trees, the seal stands on a collection of flattened clocks, with oranges dotted around the animal.

Upon further inspection, layers of painting technique become layers of a carefully constructed concept. The seal, poised and sophisticated, is covered in graffiti. Sloan says the graffiti spray serves to stand out in sharp contrast with the tranquility of the rest of the image.

Despite the sad reality of the graffiti, Sloan says his work is not meant to evoke feelings of anger or blame. Neither is he trying to take a political stance on ecological problems.

“I don’t want to create a dismal picture,” Sloan says of his work. “I’m not interested in the advocacy that takes the form of a political statement.”

His intention is to examine one particular question: “What happens when the natural world and man-made world interact?”

He answers that question by infusing every image in his painting with a purpose. The clocks represent time, the kind that continues into modernity and slowly but surely ticks away at the animal’s life. The oranges, which are a staple in Sloan’s work, are meant to be striking and bright, acting as a contrast to the subtle graffiti marks on the seal.

Perhaps the most telling aspect of Sloan’s work is his main subject, which is always an animal. Sloan uses animals “in an attempt to give voice to our silent neighbors,” he says. The animals can’t speak for themselves, so he attempts to illustrate disjointed harmony in his artworks between animals and modern aspects that are usually technological in nature.

For his other piece in the exhibit, “Birds of America: Migration Interrupted,” Sloan says he was inspired by the geese he often sees down by his studio in Denver. The piece illustrates a goose precariously wrapped in a chord.

“There’s an evolution right in front of my eyes,” Sloan says.

“Ideally, my artwork would still be readable in the future,” he says. “I want to make artworks that are long-lived intellectually.”

• • • •

Another artist featured in the exhibit is Dylan Gebbia-Richards, who moved to Colorado to pursue a Bachelor’s of Fine Arts degree at the University of Colorado Boulder. He is an artist who exploits art techniques at their most basic level to create art that appeals to all of the senses.

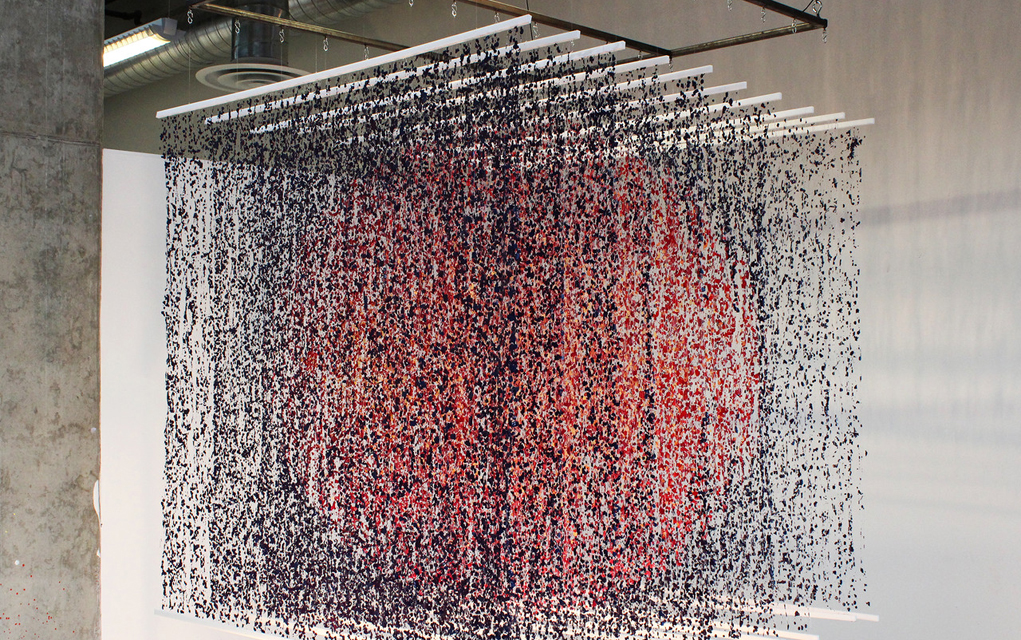

Gebbia-Richard’s exhibited piece is called “Specking” and is a series of thin cloths consisting of fragmented paint. In the exhibition’s light, the black and red fragments come together to create the illusion of a 3-D orb. Though one cannot physically walk up to the piece because it is hanging from the ceiling, glancing at it through the second-floor window yields the illusion of finely crafted beads all coming together to create a delicate optical illusion.

“There’s this perceptual adventure your eyes take through the piece,” Gebbia-Richards says. “It explores this cause-and-effect relationship.”

Gebbia-Richards explores, not the limits, the capabilities of his mediums. His work pushes boundaries, employing both the accidental and purposeful.

“There’s a logic to the random chance of the work,” he says. “And I just push it as far as it can go.”

It is only upon finishing his piece, he says, that he can see his work’s central theme is synesthesia, the phenomenon of intertwined senses where people feel colors, for example. The occurrence translates into Gebbia-Richards’ basic understanding of the world. He believes that the media in itself can be a stunning visual experimentation. The work is, however, still a visual representation of personal perception.

“I’m not imitating the natural world, but creating my own,” he says.

• • • •

Artwork is, in its most basic sense, a personal interpretation of the world. Husband and wife Mel and Bernice Strawn have their own outlooks. Even though they share a marriage, they have their own aesthetics and work on their own individual pieces. Both 86 years old and retired, the extra time allows them to work on their art constantly, with every day yielding new experimentations and results.

While the couple works individually they do share an inspiration: Japanese and Chinese art. Bernice, whose intention has always been to simplify her work, speaks about the art as teaching a type of restraint, since simplicity requires it. Mel, on the other hand, talks about being inspired by the gesture and movement of calligraphy.

Mel’s work, titled “Wire Dancer,” is acrylic paint on canvas. Mel uses bright colors and minimalistic lines to evoke the form of a configuration. The piece itself is simplistic but evocative. Smooth lines loop in the center of the piece in fluid motions that make them appear as if they are dripping down the brightly colored canvas. The fluid lines in his piece, an interpretation of wire, are inspired by the shape of Japanese characters on a hanging scroll.

Bernice’s work, “Shambala Warrior,” uses salvaged wood and paint to create a bright, impressionistic figure. For 45 years she has made constructions out of found materials. She uses both metal and wood, but mostly old wood, since she has a particular interest in it, saying the bent shapes reminded her of the shoulders of a human body.

For this piece, Bernice was inspired by the concept of the Buddhist Shambala warrior.

“The Shambala warriors are warriors for good and we need more of those around because there’s so much evil in the world,” she says.

• • • •

Each artist approaches his or her work differently. Japanese artist Yoshitomo Saito is intrigued by traditional supplies and their place in modern culture. His exhibited piece is a bronze sculpture entitled “Colorado Loop #10.” The loop, though made from a very industrial material, still resembles tree branches. They loop into the center, creating a spiral. The branches are smooth yet still contain natural-looking jagged ends and the twisting texture of a tree.

Saito works with natural imagery in his work, despite the industrialized feeling of the bronze. The piece in the show is meant to “evoke a tenacious survival spirit and the vitality of plant life,” he wrote in an email.

In the ’80s, when Saito enrolled at the California College of Arts, he was told that working with bronze was nearly primitive in the modern day. He was advised to work with other materials, but Saito was adamant about bronze. He grew to appreciate the longevity of it throughout history.

“My 30 years of challenge in bronze is a low-key independent movement, yet I see my art as an ever-lasting tea bag type while much other contemporary art expression is like fancy cocktail drinks,” Saito wrote.

No matter the labels, the genre or the medium, the art on display at the Arvada Center goes deeper than first impressions. There are too many art pieces to put a face to, but that doesn’t make it impossible to understand the artist. If a picture’s worth a thousand words then there are many stories to be found and interpreted in Art of the State.

On the Bill: Art of the State. Arvada Center, 6901 Wadsworth Blvd., Arvada, 720-898-7200. Through March 27.