Some may call Jeanette Vizguerra an advocate, a leader, a hero. Still others label her illegal. But she identifies herself as a mother — “A mother that loves her children so much and that is going to do anything that is needed to be with them always,” she says, via an interpreter. “And also I want to do everything that is necessary so that no one else has to go through what I’m going through.”

While the Aurora-based mother of four, grandmother of three, tirelessly speaks out about immigration reform, she continues to fight her own deportation and separation from her family. On Monday Aug. 24, she was granted another six-month stay of removal from officials at Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) while she continues to pursue every avenue to permanently stay in the U.S. with her children.

Jeanette walks into our interview smiling, holding the hand of her youngest daughter Zury, age 4. “Her family name is Cookie. She’s a cookie monster,” Jeanette says in English, as Zury runs to find the toys at the American Friends Service Committee office in downtown Denver. Posters of Martin Luther King, Jr. and the Statue of Liberty that reads, “No Human Being is Illegal,” hang on the walls.

Jeanette appears reasonably calm, despite the uncertainty of her present situation. She won’t know until later in the evening if her application to stay has been approved. For now, she officially has a final order of deportation and could technically be removed at any moment.

She watches her daughter play as we make small talk. Our interpreter, Jennifer Piper from the Colorado Immigrant Rights Program, brings in a pitcher of water.

After we all settle into our seats around the conference table, and Zury is content with an iPad in hand, I ask her mother to start at the beginning.

She tells me that she and her husband, Salvador, moved to Colorado in 1997 for security reasons. “It was not for money. Economically we were doing really well. He (Salvador) got paid every single day at the end of his shift,” she says.

He worked as a public bus driver, but was held at gunpoint three different times while armed men told him to drive away from crowded public areas, then robbed everyone on the bus and even called family members demanding small ransoms.

“One time I was on the bus while my husband was driving, and I couldn’t even imagine what would happen if he didn’t obey these guys,” Jeanette remembers. “They had the gun right to his head, it was so scary.”

Luckily, their oldest, and at the time only, daughter Tania was at home with grandparents.

Shortly after this happened for the third time, one of Salvador’s coworkers was found in his abandoned bus with a bullet in his head. He left behind a wife and two small daughters. “That was the deciding moment. My husband decided he needed to go elsewhere to look for a way to support our family,” Jeanette says. “It seems like since that time it’s just been one hard decision after the other.”

Salvador would go first to live with relatives in Denver, and then send for Jeanette and Tania when he could. With tears running down her cheeks almost 20 years later, Jeanette describes the day Salvador left Mexico City for good in September 1997. They sat on a bench in a park near their house and cried together. It was their wedding anniversary.

After a week, he called to say he was in Juarez looking for a way to cross the border. A week later and he called to say he had made it to Colorado. And a few months after that, he called to say it was time for Jeanette and Tania to join him.

“It was difficult to decide. My mother was pushing me to go be with my husband,” she says. “But my father didn’t want me to go. My daughter was the only grandchild on either side, and she was very well loved.”

Jeanette did decide to come to Denver, traveling with six full suitcases and a 5-year-old on a bus driven by a friend from Mexico City to Juarez. The bus was stopped at two different checkpoints, where police officers asked for identification and bribes from everyone, including several people from Central America. True to her character, Jeanette told them not to speak, knowing their accents would give them away. She would speak for them. She refused to pay any bribes and even wrote down the badge number of an especially menacing officer, threatening to report him. Everyone made it to Juarez.

She then spent over a month living in the border city, waiting to cross into the U.S. When the time came, she sent Tania in a car with an American citizen, coaching the 5-year-old to call this other woman mom. “It was scary because only my husband knew this [woman]. I didn’t really know [her], and I wasn’t exactly sure that [she] would take her to be with my husband if I wasn’t able to cross,” Jeanette remembers. “I was really nervous and really anxious, and I wanted it to be over as fast as it possibly could.”

She walked across the border with forged documents and without any issue, joining her daughter in the car on the U.S. side. But the car was stopped at a border patrol checkpoint near Las Cruces, New Mexico, where Jeanette was taken out of the car and detained. The woman, along with Tania, continued on to Colorado.

Despite consistently asking to make a phone call and how long they would be held, Jeanette wasn’t given any information about what would happen next. She was held, with another woman, at the checkpoint all day and they were fed once, each given a burrito, which was foreign to Jeanette. “They don’t eat burritos in Mexico City,” Piper explains.

Jeanette was eventually driven back to the border, where at about 3 a.m., “They put us in a gated, enclosed hallway and the only side that was open was into Mexico,” she says.

Alone in the notoriously dangerous Juarez in the middle of the night, Jeanette found herself running through the city from three men trying to rob her. While she was running, another man grabbed her and pulled her into a small restaurant. “I’ve always had a lot of luck where the right people are in my path at the right time,” Jeanette says. This man was a journalist, and after chiding her for being out alone at night, he arranged for her to stay with the restaurant owner.

It took another few weeks, but resolved to find a way to be with her daughter, Jeanette attempted to cross the border again, this time successfully. On the U.S. side, she met up with a contact her husband arranged and drove through the interior Border Patrol checkpoint early in the morning before it was open.

Jeanette made it to Denver on Christmas Eve 1997 where she reunited with both Salvador and Tania. “The first thing I did was give her (Tania) the biggest hug ever. Then we just went out to eat because I was so hungry,” Jeanette says laughing.

She both laughed and cried several times throughout our interview. Emotions that were both genuine and heartbreaking. At one point, she left the room to take Zury out to Salvador who had come to pick her up. She came back into the office shaking her head and smiling. “The woman in the hall just asked me if I was the cleaning lady,” she says. “Well that’s offensive,” Piper responds.

After that first Christmas, the first Christmas any of the Vizguerra family had ever seen snow, Jeanette struggled to set up her new life in Colorado. Unable to rent their own apartment without a social security number or credit report, Salvador and Jeanette relied on the kindness of other immigrants to get on their feet. “At each place on our path there have been people that have really tried to help us,” she says. Eventually, Jeanette began janitorial work at large office buildings around Denver. She and Salvador got individual tax identification numbers and paid taxes from the very beginning. “Even though I’m speaking out on these other things (immigration rights), I’m doing my best to follow all the rules that I can,” she says.

She worked for $5.25 an hour and then $6.20 for supervisors and bosses who were demanding, cruel and who often overworked their employees, Jeanette says. She eventually discovered she was part of a labor union, Service Employees International Union (SEIU) Local 105, and she asked for a copy of the contract. “I’ve always been somebody who’s really curious, who has a lot of questions,” she says. “I asked a lot of questions how do you file a complaint, what do you do if the police show up. You know, everything that touches that system.”

As Jeanette learned the contract cover to cover, she began advocating based on what she read for other janitorial employees around downtown Denver. “It’s always been a part of who I am from high school on … if I saw somebody doing something wrong it didn’t matter if it was a teacher or a student or a director of the school,” she says. “I would always say something.”

Eventually the leadership at SEIU asked Jeanette to work directly for Local 105, where she improved her English, traveled to other states and became well versed in politics and immigration. She also became a member of Rights for All People, an Aurora-based grassroots organization fighting racial and economic injustice, where she served for 13 years.

“A thousand things happened in those 13 years,” Jeanette says. “I was able to really learn how to stand up for your rights and win,” she says. “I also learned to have a good instinct who was actually fighting with their heart for people not just cashing a check.”

Plus it gave her a strategy to fight her own immigration battle, as she knew exactly what she had to do when she was first arrested, and how she had to do it.

In 2009 she was pulled over while driving from her second job to apply for a third job. At the time Salvador was recovering from cancer treatment, and she was the only member of the family bringing in any income. The cop said he pulled her over for dirty plates — as in the license plates were too dirty to read. The first question he asked: “Are you legal or illegal?”

With all of her experience in the labor movement, Jeanette knew her rights and refused to answer the question. She was arrested for driving without a license, never ticketed for anything on the vehicle, and her immigration case began.

After her arrest, the officer found papers in her purse that she was planning to, but hadn’t yet, use to get the third job. Although she had been told the papers were forged — a made up identity — they were actually stolen. She was charged, and eventually convicted, with a misdemeanor in Arapahoe County. “That’s important because ICE views identity convictions as an issue of moral turpitude, that you have bad moral character,” Piper says. “The whole immigration [system] functions on this idea of good moral character and has for over a century. So the burden on you is to prove you have sufficient good moral character that you should be allowed to stay.”

Jeanette was detained for 34 days at the private, for-profit Aurora Detention Facility operated by the GEO Group. That’s when she began a very public campaign through Rights for All People, as she was still fighting the identity theft charges.

“I wanted to do the campaign not only based on my own experience, but of the experiences of so many other women that I met and heard in detention,” Jeanette says. “I left detention with so much rage at the injustices that were happening and I wanted to give voice to that. I wanted people to see what was happening every single day.”

She recognized the risk of vocally and publicly raising awareness, but Jeanette, already in deportation proceedings, felt she had nothing to lose. “I knew it was a double-edged sword to have a public campaign. It could be something that could help me in my case or it could be something that would give them a reason to get rid of me quicker,” she says.

In 2011, at 8 a.m. on a Monday morning, more than 300 people supported Jeanette at immigration court, but the judge denied her plea to stay in the country. “The judge found that the hardship and suffering her kids would face did not mean the extreme bar,” Piper says. But he “did recognize that her moral character was impressive.”

Not one to give up easily, Jeanette decided to appeal the judge’s decision. But while she was waiting for a court date, she received word that her mother was dying in Mexico City, and she went to visit her.

“All I could think about was the love I had for her and love she had for me,” Jeanette says choking back tears again. “Papers are important but they’re not more important than that. Nothing was more important than that final opportunity to see her. And I did know what it meant, what it implied, leaving.”

While Jeanette was in route to Mexico City, her mother passed away. She spent the next seven months living with her father, away from her children, trying to find work in a place that no longer felt like home. “The people that I knew, the friendships that I had, they aren’t there anymore. It’s not like I’m going back to where people are still together,” she says.

Plus, despite her efforts, Jeanette could barely support herself, let alone three young children. “There’s age discrimination to get jobs. I’m old. It’s 18 to 35 who gets the jobs,” Jeanette, 43, says. “Here, it doesn’t matter how old you are, you can find work and make a paycheck.”

And Mexico City sees even more crime and violence now than in the ’90s, when Jeanette first left. According to the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, there were 10,073 homicides reported in Mexico in 2000. In 2012, the year Jeanette went back, there were 25,967 or a rate of 21.5 people per every 100,000. The U.S. had a homicide rate of 4.7 per 100,000 that year. “How can a judge or somebody who doesn’t really know Mexico, how can they say my children are not going to suffer there? What do they really know about Mexico?” Jeanette questions.

So she attempted to re-enter the U.S. by hiking across the mountains near Chihuahua. Unfortunately for her, two border patrol officers were also hiking those trails and detained the entire group. Jeanette spent almost two months in detention in Texas, before being transferred back to GEO’s immigration facility in Aurora where she spent another week and a half before she was released.

“The people who worked for GEO treated us like we weren’t even human, not criminals, but not even human,” Jeanette says. “You already went through immigration court, you’ve already paid your debt, and now you’re in this place where these private guards are treating you like you’re not even human and humiliating you.”

She then received her first stay of removal for six months. She has applied for three more stays since then, the second of which included a work permit valid until June 2016. The one approved on Monday is her fourth six-month stay, and the process has taken its toll. “People see me as super strong and I have everything under control and I know what I’m doing while inside I am breaking into a million pieces and falling apart,” Jeanette says. She has since seperated from Salvador.

But despite all the setbacks, court dates and hardships, Jeanette and her family remain hopeful. Plus, they have been inundated with community and congressional support, as there have been multiple rallies and both Rep. Jared Polis and Sen. Michael Bennet have written letters on her behalf.

“All of the work and the seeds that I plant along the way seem to give fruit at the last possible second. And that’s my intuition in this moment,” Jeanette says. “Everything I’ve been doing is correct, and at the end of the day it will have results. And every resource that crosses my path I gather it up to use it at the right moment.”

And she may be right. Although ICE has only granted her another six months instead of the year she was hoping for, Jeanette received a U Visa certification from the Denver Police Department on the afternoon of Aug. 21. A U Visa is reserved for victims of certain crimes who aid officials in the investigation and/or prosecution of that crime. As a victim of a crime over 12 years ago, the details of which she was unwilling to talk about, Jeanette is cooperating with the investigators making her eligible for the three-year visa, with which she can apply for permanent residency and then eventually citizenship. The police department certification does not guarantee her the U Visa but it does help her case with ICE as U.S. Citizen and Immigration Services (USCIS) processes her visa application.

“The agency’s (ICE) standard practice is not to deport someone who is in the application process. The whole point of the U Visa is for people who are undocumented to feel safe enough to come forward and cooperate in an investigation,” Piper says. “So if you deport during that process…”

There is a U Visa quota each year, which will most likely be met by the deadline in October. Plus the application could still take Jeanette and her lawyers several months to complete. But USCIS can make a provisional determination at any point throughout the year, and Piper says the family is hopeful they will hear back before this most recent stay expires in February.

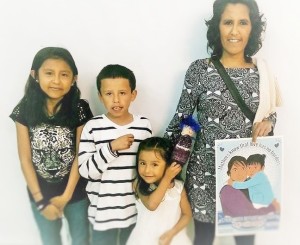

While Jeanette slowly goes through the process, she’s spending as much time with her children as possible. She describes recently spending all day with Zury, Luna, 11, and Roberto, 10, learning about their new passions and talents, as they were getting ready to start school. In these moments she finds strength and resolve to keep fighting.

But she does admit that her legal troubles are having an affect on her kids. “Sometimes when they are playing they talk about when they grow they will tell other people about the fight that we’ve raged and the things we’ve done together,” she says. She describes watching her youngest daughter, Zury, re-enact different situations with immigration and police officers rather than playing with dolls like she should be.

With her background in child psychology from Mexico, Jeanette recognizes the impact the immigration system is having on U.S. citizen children — children like Zury, Luna and Roberto. “They are really the future of this country and the psychological damage that is being done by the system that we have now is going to have impacts for generations to come,” she says.

“The system is making them mature and grow up faster than they need to,” Jeanette continues. “It’s also making these children very sensitive to what’s just and what’s unjust because they see directly the impacts of the laws that we have on their parents.”

If in the end, ICE and/or USCIS rejects her applications and she ends up back in Mexico, she says she’ll leave her children in Colorado with Salvador. “If they win and deport me, I will go alone. If somebody has to make a sacrifice it will be me not my children,” she says.

If that happens, she plans to move as close as she can to the U.S.-Mexico border and rely on American friends to bring her children across to visit as often as possible. And she speaks frankly to her children about the situation they are in. “I think that I have given them the confidence to know that even if things get really difficult that I will never stop fighting for us, no matter what happens,” she says.

And as she pledges to keep fighting the prejudices, stereotypes and injustices she’s both seen and been subjected to as an undocumented immigrant in the U.S., she’s also aware of the current national conversation in both news and politics regarding immigration reform and immigrants themselves.

Her response is simple: “I want you to look into your history. I want you to learn more about your family. It’s almost for certain that your ancestors are not from here. And that person that immigrated here came here so that you would have the privilege that you have today. So that you would be able to be the person you are with the rights and the privileges that you have as a citizen,” Jeanette says. “That all started with someone just like me.”

CELEBRATE WITH JEANETTE AND HER FAMILY: 1:30 p.m. Saturday Aug. 29, Ralston Central Park and Splash Pad, 5850 Garrison St., Arvada.